The United States is working hard to stifle its position in the world market under President Donald Trump. But in the rest of the world, globalization is still proceeding steadily.

When you said “globalization” in the 2000s and the early 2010s, it was frequently simply meant “moving manufacturing to China,” but that’s now pretty much over. Inbound foreign direct investment has dropped off a cliff, and businesses are now trying to pull their cash out. Blame a combination of rising labour costs, the closing off of the Chinese domestic market, and “de-risking” over fears of battle.

However, this doesn’t think China will just shut itself off from the rest of the world and vanish. Far from it. China will change from being a , destination , for strong funding to being a , source , of funding. A whole bunch of Chinese companies are going to build factories ( and offices ) in other countries.

In reality, this is already taking place in a significant manner. Kyle Chan ( whose website I highly recommend, by the way ) has a really excellent article about this trend.

He states:

Chinese firms are racing to develop companies around the world and build new global supply chains, driven by a desire to avoid taxes and safe access to marketplaces.

Chinese businesses have been setting up factories in big target markets like the EU and Brazil. And they’ve been building flowers in” cable countries” like Mexico and Vietnam that offer access to developed industry through trade agreements.  ,

Morocco, for instance, has emerged as a surprisingly common destination…due to its trade agreements with both the US and the EU…Countries across the developed world and the Global South everywhere are keen for Chinese firms to build businesses in their industry, with the promise of new tasks and new technologies.

Kyle’s excellent map demonstrates how global this boom in investment is:

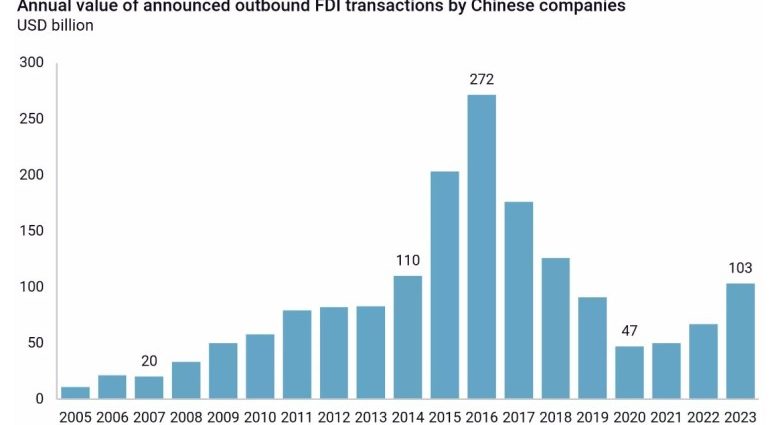

This boom in overall numbers may seem a little unintuitive. As Rhodium Group reports, a large portion of China’s official , completed , outbound investment is actually “phantom FDI” — Chinese companies keeping their earnings outside of China by pretending to do FDI. And when you look at FDI  and announcements, the total is still significantly below what it was in the middle of 2010:

However, this overall decline obscures a significant shift in how much FDI China is doing, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Up until the pandemic, China’s foreign investment was focused more on acquiring foreign companies, usually in developed countries — basically, Chinese companies bought American/European/Japanese/Korean companies so that they could A) get their technology, and B) use them as local beachheads to sell stuff to rich consumers. The mid-2010s saw a significant boom.

Since 2022, however, China’s focus has shifted dramatically to “greenfield” investment — Chinese companies are building their own offices and factories overseas:

The auto and energy sectors account for the majority of this new wave of greenfield FDI:

Basically, the Chinese auto and battery industries are going global. In addition to his post, Kyle has written in a fantastic thread about the plans to expand BYD, China’s flagship automaker, and its most notable business.

Greenfield FDI is in many ways more of a boon to the receiving country than M&, A, when you build new factories and offices in a country, it creates new jobs, and often transfers new technologies, instead of just changing the ownership of an existing business. And unlike M&, A, greenfield FDA frequently targets developing nations because it’s typically at least partially concerned with lowering costs.

So it makes sense for developing countries around the world to be a lot more excited about the flood of Chinese investment now than back in 2016. Additionally, we should anticipate that this wave will be more resilient than the previous one because it is driven by Chinese costs and by mature Chinese businesses with long-term interests in foreign markets.

Generally speaking,  , this is how economic development is supposed to work. As economies become more expensive, countries are forced to shift production to less expensive locations. China was the cheap place to make stuff 20 years ago, now, it’s places like Vietnam, Indonesia and Morocco. Manufacturing companies frequently fly from one country to another, helping each one to become industrialized along the way like a flock of geese.

Also, it’s easier to sell products in a country if you also produce those things inside that country — transport costs are lower, you can get a better understanding of the local market, and you can more quickly respond to local changes in demand, policy, and so on. Additionally, there are currently a number of tariffs to take into account; if those products are made in Europe, they will be much friendlier to Chinese companies.

So we should generally view China’s outbound investment boom as a great thing for the world. It is assisting in industrializing developing nations like Morocco and Indonesia, as well as diversifying and modernizing the economies of middle-income nations like Brazil, Turkey, Mexico, and Thailand. Chinese-led globalization is looking like a positive alternative to America’s bizarre, ideologically-motivated retreat from the world economy.

However, there are indications that China will no longer be as welcoming and helpful as it was in the 1990s and 2000s. Kyle reports that China is trying to isolate the world’s biggest and most important developing country from its new economic world order:

Beijing is trying to influence the Chinese industry’s global expansion, including which nations they invest in and how. Beijing is encouraging Chinese companies to build plants in “friendly” countries while discouraging them from investing in others in a kind of “industrial diplomacy” .…India represents the most striking case of Beijing’s effort to shape the international behavior of Chinese firms …]A ] cross a number of industries, Beijing seems to be discouraging Chinese firms making future plans to invest in India while also limiting the flow of workers and equipment …

Beijing appears to be restricting the flow of Chinese equipment and workers to India, which would otherwise restrict Apple’s manufacturing partner Foxconn from . Some of Foxconn’s Chinese workers in India were even told to return to China. This informal Chinese ban covers businesses that work in India, as well as other electronics manufacturers. Beijing has warned Chinese automakers to avoid investing in India.

Why is China doing this? According to Kyle, one possible cause is geopolitical spite, and China appears to be restricting investment into the Philippines, which it has a territorial dispute with. China also has a border dispute with India. And to be fair, not all of the chit is from China; some Chinese leaders have also blocked Chinese investments.

But it’s fairly obvious there’s something more strategic going on here — China doesn’t want to build up the manufacturing capabilities of its biggest potential rival.

India is now the most populous nation in the world, having overtaken China a few years ago. Its GDP is growing faster — it grew 6.5 % in 2024 and 9.2 % in 2023, significantly faster than China. And as the Wall Street Journal reported back in 2023, it’s been making a push to become a global manufacturing hub, much like China did in the 2000s:

Western companies are desperately looking for a backup to China as the world’s factory floor, a strategy widely termed” China plus one” .…India is making a concerted push to be the plus one…Only India has a labor force and an internal market comparable in size to China ‘s…Western governments see democratic India as a natural partner, and the Indian government has pushed to make the business environment more friendly than in the past …] India ] scored a coup with the decision by , Apple , to significantly , expand iPhone production in India, including , expediting the manufacturing , of its most advanced model …

After decades of disappointment, [ India ] is making progress. Its manufactured exports were barely a tenth of China’s in 2021, but they exceeded all other emerging markets except Mexico’s and Vietnam ‘s…The biggest gains have been in electronics, where exports have tripled since 2018 to$ 23 billion… India has gone from making 9 % of the world’s smartphone handsets in 2016 to a projected 19 % this year…

Foreign direct investment into India increased by$ 42 billion annually between 2020 and 2022, which is doubling in less than a decade.

India’s electronics sector has  , especially taken off, helped by specific government incentives and by Apple’s decision to locate much of its production in the country.

India’s manufacturing sector is still hindered by some poorly designed policies, particularly those that impose tariffs on imported components, which make it difficult for India to carry out the kind of assembly work that helped China expand in the 2000s.

But the country’s infrastructure has improved by leaps and bounds, and the government has made some progress in reducing red tape. The government should increase that momentum by easing the burdensome regulations even further, promoting education and labor mobility, and shifting from protectionism to export promotion.

But the most important reason companies want to make things in India isn’t low labor costs — it’s the lure of the company’s domestic market. Establishing factories in India means opening a door to 1.5 billion people with rapid income growth.

Remember,  , scale matters in manufacturing. The lower your costs go, the more units you can ship, and the more competitive you become. It’s going to be a while before Indians can all afford the latest and best electronics and cars and appliances, but soon they’ll be able to afford unbelievably huge numbers of the pretty-good stuff. Any business that capitalizes on that demand won’t just generate tons of revenue; it’ll also lower its costs.

And unlike China, India probably won’t force out multinational companies once it has  , strip-mined them , for their technological secrets. India offers a unique opportunity to expand its market that China has never had. Of , course,  , companies want to put their factories there, just as soon as government policy makes it feasible to do so.

At first, multinational corporations will export their best technology to India, focusing solely on low-quality assembly work. But as Indian manufacturers master those simple tasks, they will start to climb the value chain, learning how to do more complex processes and make higher-value goods. When that happens, multinational companies will have a better sense of why they should invest in higher-tech projects in India.

Eventually the Indian companies themselves will get so good that they’ll be able to create their own brands, start doing R&, D for themselves, and compete on the global stage, using the advantages of scale that they get from knowing their home market better than anyone else.

This implies that multinational corporations are naturally inclined to train their future rivals. Nowhere was this effect more powerful than in China, where European, American, Japanese and Korean companies offshored production to China in the 1990s and 2000s, then found themselves competing with Chinese companies in the 2010s. Many Americans now consider that allowing this to happen was a grave tactical error.

China’s leaders probably concur with that assessment, and are determined not to make a similar error with respect to India. To take advantage of India’s cheaper labor and sizable domestic market, it would be less expensive for BYD, CATL, or Chinese electronics companies to relocate their factories to India.

But in the long run, that could risk speeding up the technological development of Indian rivals to Chinese manufacturers, as well as making India itself rich enough to challenge China on the world stage.

People in China are, undoubtedly, considering this possibility. In , a great article , back in 2023, Viola Zhou and Nilesh Christopher wrote about how Chinese engineers working at plants in India felt like they were training their own replacements:

Chinese engineers occasionally discussed how they were working to make their own jobs obsolete, according to Li. One day, Indians might become so adept at creating iPhones that Apple and other global brands could not operate without Chinese workers.

Three managers said some Chinese employees aren’t willing teachers because they see their Indian colleagues as competition. However, Li asserted that progress was unavoidable. ” If we didn’t come here, someone else would”, he said. This is the turning point of history. No one will be able to stop it”.

This was undoubtedly the experience of Korean and German engineers working in China in 2007 or 2012

But it’s not just that Indian , companies , might one day compete with Chinese ones. India and China will be the most powerful in a world where economic development is largely evenly distributed because they have by far the largest populations in the world.

So if China wants to stay much more powerful than India, it has an incentive to make sure that economic development is not evenly distributed — that the new wave of globalization skips India entirely.

China’s leaders are likely to envision a new global economy with lower-quality assembly jobs in other nations, low-income manufacturing, and a service-dependent backwater like India.

India, of course, doesn’t want this, and it has some powerful natural allies. Other highly developed nations, such as Germany, Japan, Korea, France, and others, want to stop China from establishing a future in which they will dominate the world. The best way to do that is to invest in India.

Of course, the US ought to be India’s most significant and valuable ally in this conflict. A rational and reasonable US would be trying to encourage as much investment as possible in India, and to boost India’s technological capabilities and income level as fast as possible.

However, the days of the US acting rationally and justly are over, at least for the moment. America has retreated from the world, engaged in internal struggles, and shattered by its own bizarre ideology.

So India needs to focus on partnering with the world’s other developed countries — with Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Canada and the nations of Europe. It needs to maintain cordial and friendly relations with these nations, ratify free trade agreements, lower or eliminate tariffs on imported goods, expand business-friendly policies, encourage more inbound FDI, and generally integrate itself into a global bloc that includes every wealthy nation that opposes China’s rule over the world economy.

The withdrawal of the US will create headaches for India, as will China’s determination to keep Indian manufacturing down. However, India still has a lot of places where it can invest in technology and technology. And in the long run, its natural advantages will allow it to industrialize and grow rich, regardless of the forces arrayed against it.

This article was originally published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack, and it is now republished with kind permission. Become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.