US President Joseph Biden announced a thaw in China’s ties with the US. However, there is much more ice than meets the eye in this “thaw.”

When the US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo returned from China last week, she declared that the US “won’t tolerate” China’s ban on Micron chips. Still, from Beijing’s perspective, why should China tolerate restrictions on tech supplies?

Then what will happen to China’s purchases of US Treasury bonds, for decades a cornerstone of bilateral ties and now extremely important because of the US budget crisis? Will they go ahead, or will China stop buying them or buy less? How will it impact the US and the global economy?

The urgency of Raimondo’s pressing to meet the Chinese side, the rush with which Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen moved in the following hours, told China that the US was in big trouble over the budget.

Speaking of a thaw and US government officials knocking on Beijing’s door to talk could give the impression in China that America is eager to mend fences with China because it feels weak.

Until a couple of months ago, all the messages coming from Washington were of fire and brimstone. Then, in March and April, the US budget crisis began and a problematic agreement had to be found between Democrats and Republicans to deal with it.

A not insignificant part of the budget goes into defense spending and generally to support domestic development plans aimed at national growth against Beijing.

It all looks very odd from Beijing, where people wonder: there is tension, but you want our money; what is it, a show?

Indeed, China has more than one reason to ask what’s happening and bargain with Washington. The US, keen on China’s bond purchases, has conceded something, although it is unclear how much.

In any case, China’s bond purchases have apparently muffled the recent saber-rattling. In the near future, the impression is that American allies will restrain controversial moves on Taiwan and elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Beijing will follow the problematic, divisive US election campaign with two candidates who are both weak on paper.

The Republican Donald Trump, more controversial than ever, is hounded by lawsuits and denunciations that make him a martyr to his follower base. The democratic Joseph Biden is cast by his foes as tired, fatigued and unable to handle the stress of the presidency.

Things should be under control for the next 18 months; there shouldn’t be a major bilateral crisis, Beijing seems to figure.

Central Asia’s moves

But politically, there is a lot of movement around China.

Tehran, on May 28, announced that talks have progressed between Iran and the US on releasing Tehran’s frozen assets in Iraq and South Korea, and an agreement on general terms will likely be achieved in the coming days. It could spin the political calculus of the area in a different direction.

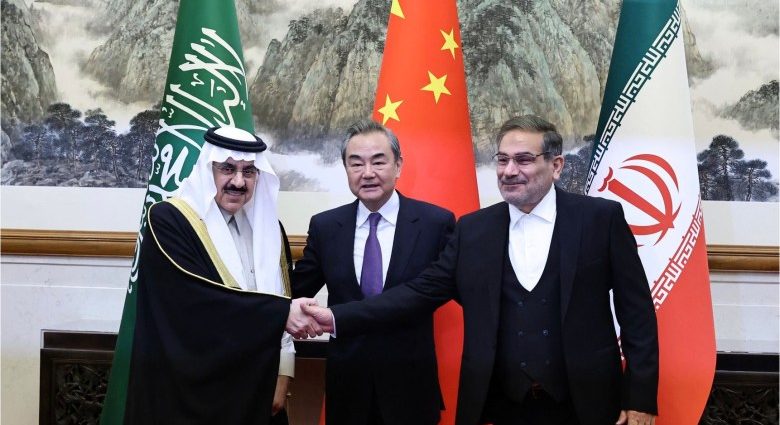

Just two months ago, on March 10, China announced it had brokered a historic deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia. It inserted China into delicate Middle Eastern politics and seemed to sideline the US, recently battered in the region by the ruinous wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Still, at the beginning of April, CIA director William Burns visited Riyadh to confirm bilateral ties, as the US guarantees security to the Saudi court.

Now, the Iranian announcement could also pave the way for historic and new relations between Saudis and Israelis, which had been in the offing for years. Moreover, Iran’s new posture could turn the country to a new approach with Israel.

Certainly, nothing is set in stone but the US-China rivalry has extended to Central Asia and the Middle East, and it might have an overall positive spin for everybody.

China’s recent inroads in the region could have started a complex reassessment. This created a new Chinese presence and role in the area and spurred America to be more active, possibly taking Israel along.

China is not marginalized in this game, but certainly neither is the US. The two countries seem ready to play in the region according to different rules. This may change the political geography of the area, and no one is clear who will be the winner in the end.

Besides, the G7 met in Japan, inviting India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Australia and Brazil. It found unity on a platform against China. However, there is no longer talk of “decoupling” but rather “de-risking.”

Among America’s allies, there is no agreement to decouple economically from China. It may seem like a step forward from Beijing, but it may be more complex.

There is an agreement to take away the Chinese risk, which is already factored into companies’ budget plans. Those inflate all ventures dealing with China.

The new costs, sanctions and restrictions budgeted in China’s companies’ plans make all foreign enterprises in the country less convenient. In recent years, burgeoning tensions and drastic anti-Covid measures have pushed foreign investors to isolate their China operations from the rest of the world; new costs make it less convenient to operate in China altogether.

Still, if processes are still active in the country, the promising Chinese markets are no place to flee. But new operations are less attractive.

While the G7 was convened in Hiroshima, China invited the five former Soviet republics in Central Asia (the five Stans) to Xi’an, its ancient capital. The five Stans occupy a territory about half the size of China, with just over 70 million inhabitants.

The signal was against the G7 and Moscow, the former ruler of the region. With the extension of its reach into the Stans, Beijing projects to the Caspian Sea, i.e., the Caucasus, i.e., the Black Sea and to the great Mediterranean.

It claims that the G7 resolution is weak and that Russia’s eventual defeat in Ukraine does not harm Beijing. On the contrary, it allows China to extend its impact where it had never gone before, bringing closer border contact with Iran and the Saudis.

There are reasons to be not so gloomy in Beijing. The urgency of US talks on bond purchases suggests more generally that there is something very wrong with the US economic situation and model.

China may have its own internal economic difficulties: the crisis in the real estate sector, the problem in the trusts sector and the challenges of local governments. Still, without full currency convertibility, the central government can better manage its economic affairs, and thus political bargaining, than Washington. Or can it?

It is time for observation and thinking about the extensive framework that still holds bilateral ties together. Here, constraints are very tight for Beijing.

A two-way surplus

Over 30 years ago, the US and China established a framework that constrained both countries. This framework is presently under duress, but it is still there.

The US is still giving China its largest surplus. Last year, it was about $700 billion. Without the G7, China would not have a surplus; it would have a deficit. The domestic economy would not be the same.

If there were a trade deficit, China should export its currency or change its entire trade strategy. Both options, however, are problematic.

With the currency export option, there would be a foreign RMB (freely-traded abroad) and a domestic RMB (with a rate adjusted by the central bank), and their exchange rates would differ. It would lead toward the free exchange of the RMB, which the government doesn’t want.

Changing Chinese trade is not easy either, because developing countries do not have much purchasing power to acquire so many Chinese goods.

Furthermore, factories will close once China does not have today’s surplus, and workers will lose their jobs. Then, there will be a social and political crisis.

China uses part of its surplus to buy US debt. The United States needs China to buy its debt to buy Chinese goods. The whole process, though, has stopped being cost-effective for the United States.

The United States buys hundreds of billions worth of goods yearly, so the total deficit with China in many years is many trillion dollars. But China buys only $1 trillion in US Treasury bonds.

By some accounts, the United States has transferred trillions of dollars to China in 30 years. This calculation is simplistic and partial, but reflects something visible in the two countries: China is bridging the economic gap with the US and has grown much faster than America in the past 40 years.

America thinks China should be grateful for this. It isn’t; it’s rather unhappy with America.

China can spin a story at home about addressing the issue, but abroad there is a growing consensus that something is wrong with how China handles its trade.

Then, would China be prepared to handle a long-term trade deficit? It would have to bear its costs. China can manage a trade surplus easily; a trade deficit is far more complicated.

Managing a long-term deficit requires convincing other countries to accept your currency in exchange for real goods. Therefore, it also entails two elements:

- Long-term internal reliability and stability (a fairly transparent political system, a military, accepted diplomatic and cultural clout, etc)

- Allowing other countries to make money in China and quickly removing the hurdles. It would need an advanced stock market and the development of new technologies that can create new markets and drive global growth, which can be exported to other countries. The new markets will bring new opportunities to prosper.

The United States and its old “buddy” Britain have both elements. Others are different. Even Germany and Japan rely on exports.

If the framework is not rapidly fixed, it will fall apart after the present lull and America and its allies will have established a new framework with other countries. China certainly has plans and is preparing, but of course, it’s unclear whether they will work.

Here time is of the essence. Is time on China or America’s side?

China may think that the longer I have, the better I can prepare for the coming conflict; a bigger economy can withstand the pressure, while American divisions will rip it apart over a longer time.

America may think the longer I have, the better I can consolidate my alliances and the weaker Russia becomes, surrounding China with more problems that will come for China’s sputtering domestic economy.

But, in the meantime, the crux of the matter might be different as both sides bide their time and draw the wrong conclusions about the other side’s weakness. The thaw doesn’t seem set to last and brewing troubles will get bigger and possibly come back with a vengeance.

Moreover, is the lull real? Aside from any rational calculations, the world around China is exceptionally volatile and many things can blow up, irrespective of Beijing’s intentions.

US domestic strife can find a sudden unity for any given incident, coalescing against China, the common denominator of the nation. Then, the issue of China’s bond purchases could vanish. Chinese assets abroad would be seized or frozen, as the same would happen to Western holdings in China. It was already the case with Russia.

Meanwhile, can there be a systematic solution to avoid a war? And what will be the price for peace? At the moment, not many seem to think about that.

This essay first appeared on Settimana News and is republished with permission. The original article can be read here.