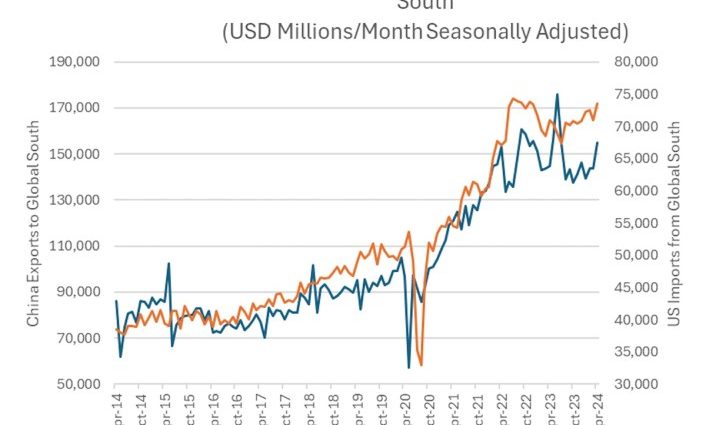

Contrary to a meme that’s common among American policy experts, there is no Chinese “export wave”. China’s imports to developed nations have stagnated for years, but they have increased to the World South.  ,

Not only have China’s export to the International South in full risen by an extraordinary percentage, but its imports to every area of the Global South – Asia, Latin America, Africa, Middle East/North Africa and Central Asia – have risen in lockstep

Certain, some of China’s export success in developing nations is due to a novel type of triangular trade, driven by the 25 % tariff on some$ 200 billion of Chinese imports that the Trump administration imposed in 2019. China boats pieces and investment products to Mexico, Vietnam,  , India , and different countries, which then assemble them into finished goods for sale in the United States.

Asia Times earliest documented this great circumvention of US levies in an , April 3,  , 2023 , research. Since , then , the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Bank for International Settlements and the Peterson Institute have published reports documenting the same conclusion:  , America is more reliant than ever on Chinese supply stores.

China’s exports to the Global South ( left- hand scale ) are tracked by US imports from the Global South ( right- hand scale ), with a lag of about two months.  , China’s exports to the Global South have jumped from about$ 90 billion a month in 2020 to$ 150 billion a month today, or by$ 60 billion a month. About half of that, or$ 30 billion a month,  , shows up as higher US imports from third countries. About half of China’s trade rise to the Global South is attributed to the improvement of Taiwanese supply stores to the developing world, or to be shortened.

The other half comes from sectors that China has dominated over the past few years:

- energy cars,

- thermal panel,

- modern equipment,

- transit systems, as well as

- electrical products.  ,

Amazingly, British researchers have n’t commented on this great movement of Chinese business, which is by far the most important development by far in the world economy in absolute figures.

A discussion view of China that nearly every scheme shop in the US approved proved to be incorrect as any prediction may be.

The compromise, expressed often on Fox News by Gordon Chang and promulgated in books by , Axios’ , Bethany Allen , and , Dan Blumenthal , of the American Enterprise Institute,  , as well as a host of small pundits, stated that China was in decline if no crisis, and that America’s restrictions on export of sophisticated chips would infuriate China’s scientific ambitions.

China not only worked around the tech sanctions, but it also worked around US tariffs. China has had a plan, expressed at a high level in the Belt and Road Initiative, to replicate some aspects of its industrialization in other countries of the Global South, or what I called” Sino- forming” in my 2020 book,  , You Will Be Assimilated.

In 2015 I toured Huawei’s sprawling Shenzhen headquarters with a group of Mexican diplomats. We watched their product line and listened to a lecture about Mexico’s shortcomings in digital broadband and the fantastic things it could do with low-cost high-speed data.

I applauded the author for the breadth of the study and inquired casually whether Huawei had created this content just for the occasion. ” No”, I was told. ” We have digital plans for 100 countries. You can look them up on our website”.

China’s export success in the Global South, in short, is the economic equivalent of Babe Ruth’s apocryphal pointing to left field, followed by a home run in the same direction.  ,

American analysts ‘ sheepish silence on the subject is not just ignorance or sloth. It reflects an unwillingness to own up to a catastrophic, collective policy failure. Virtually everyone in the American policy community agreed that a restraint should be placed on China’s rise as a global power, and that a ban on American technology exports would keep China at a loss.

The Trump Administration stopped the export of advanced chips to Huawei, which caused the first shock , which prevented it from producing 5G-capable chips that it created in-house and produced in Taiwan. Because Taiwan’s dominant foundry SCMP used American technology in the manufacture of Huawei ‘s , 5G , chips, Washington asserted extraterritorial control. Without access to advanced chips, US analysts thought, China would be unable to roll out its national 5G network.

Five years later, China has about 3.8 million 5G base , stations in place, while , the US has just 100, 000. Huawei learned how to construct base stations using older-generation chips produced in China.

The second shock occurred in October 2022 when Washington decided to impose a “nuclear option” by limiting access to all Chinese companies, not just Huawei. A year later, Huawei launched a 5G smartphone, the Mate 60, with an advanced 5G chip produced in China by a workaround process that American regulators had thought impossible.

The US policy community ca n’t admit that it was collectively, catastrophically wrong, and is groping for an explanation of Chinese success. That is the motivation for the popular meme that China has created “overcapacity” in manufacturing, and threatens the , the world with a” second China shock”, as the , Wall Street Journal , wrote on March 3.  ,

The trouble with the notion of a “second China shock” is that China is exporting less, not more, to the developed markets with which it competes directly, and exporting a great deal more to the Global South, which has virtually unlimited demand for $10,000 energy cars, cheap solar panels and broadband infrastructure.

Promoting that idea is less embarrassing than examining the underlying patterns in the trade data and coming to the conclusion that US policy toward China has been a humiliating failure.