Reshoring the British business has become a nonpartisan policy goal because Biden had a lot of interest in it. The concept has always been met with skepticism from a variety of angles.

Anything that involves tariffs and/or professional policies is viewed with suspicion by some economists and completely traders. And politics being what it is in America, both Republicans and Democrats have undoubtedly doubted the capacity of the other party to fulfill their promises. But in addition, I typically encounter a healthy skepticism about America’s skill to perform manufacturing , at all.

Americans may be forgiven for having this idea. Most of our lived knowledge has either been the Rust Belt time of the 1980s, or , the charged offshoring , of the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s. America has not had a factory-building increase in a very long time.

On top of that, most people who take economics in America know only one theory of global business, which is the principle of , analytical advantage , — generally, the idea that countries specialize in whatever they are best at. Because of the decades-long trend, it’s reasonable to assume that America focuses on technology and service rather than producing real goods.

If you think that, you likely think that reshoring production will always be a difficult, if not impossible, task. Sure, with sufficient taxes and grants we could , force , Americans to get more expensive products made in America, but this will render us all poorer. Why not concentrate on what we appear to be good at and left manufacturing to the East Asians and perhaps the Germans?

And still the right way to think about business isn’t always the best one. There ‘s , another theory , that says that since America has tons of money and technology, we can accomplish a lot of automatic production. And there ‘s , but another theory , that says that because the universe loves multitude, the US can produce near variations of the stuff the Asians and Europeans make.

Since the turn of the century, the US has experienced underdevelopment, which may have been due to an overvalued exchange rate, intentional Chinese rivals, and US business laws that favored the financial industry over the manufacturing industry.

The common belief that Americans just aren’t good at making stuff seems contradicted by areas in which we are  , startlingly good at making stuff , — for example, SpaceX, which is pumping out the world’s best rockets from US factories in stunningly high volumes. The American South has also become a hub of high-quality auto manufacturing, with the help of Japanese and South Korean investment.

If that’s true, then reshoring has a chance. Although the uncompetitive dollar will continue to be a major issue, tariffs and other trade barriers can prevent Chinese competition, and US industrial policies can switch from pro-finance to pro-manufacturing ones. In fact, this approach is already bearing fruit in a number of strategic industries.

Take , solar power, for instance. The collapse of US manufacturing and China’s overwhelming dominance for years served as the industry’s main story. In , an article in Bloomberg , last September, David Fickling lamented:

The US and Europe’s disregard for their own clean-tech industries is the result of myopic corporate leadership, timid financing, oligopolistic complacency, and policy chaos. That left a gap that Chinese start-ups filled, sprouting like saplings in a forest clearing.

But even before that story hit the presses, things had already begun to change. In December, the Solar Energy Industry Association  , reported , that US solar manufacturing capabilities are on the rise:

In 2017, the US ranked 14th in the world for solar panel manufacturing capacity. With a focus in the South, additional factories started popping up all over the nation with an emphasis on expanding existing facilities starting in 2018 and then accelerating in 2022. Today, the US has leapfrogged competitors and ranks 3rd in manufacture of solar panels, passing large solar manufacturing countries like Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Turkey…A new report by SEIA and Wood Mackenzie found that the industry had reached a critical threshold:

US solar manufacturing has reached a critical point following a record-setting Q3. American solar module factories can now produce enough to meet nearly all the demand for solar in the US when they are at full capacity.

As more solar deployment happens, more manufacturing will come online…Companies are investing billions of dollars to produce American-made solar panels in states like Georgia, Ohio, Texas, Washington, South Carolina, and Alabama…]T] here are more factories on the way, either announced or under construction.

Although it is obvious that the US is still far behind China, this growing trend of production and self-sufficiency is very different from the typical narrative you hear. As the article notes, the reshoring of solar began in the late 2010s, under Trump, and may have had something to do with Trump’s tariffs on solar panels. A second round of tariffs, courtesy of Biden, went into effect near the end of 2024, and definitely seemed to have an effect on solar imports:

However, Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act was the real catalyst for solar reshoring:

For another example, look at , semiconductors. I ‘ve , written a lot , about how the CHIPS Act has galvanized U. S. production in this most strategic of all industries, including major investments from Taiwan and elsewhere. This is from , a recent report , by the CHIPS Program Office:

Over the past four years, there has been more investment in electronics manufacturing in the United States than in the last three decades combined. Plans for investments totaling nearly$ 450 billion are now available, making this the largest wave of semiconductor manufacturing growth in US history. This includes the two largest domestic investments in semiconductor manufacturing by US companies in history ( Intel and Micron ), as well as the two largest foreign direct investments in new projects by any company in history ( TSMC and Samsung ) …Perhaps most significantly, for the first time, all five of the world’s leading-edge logic and dynamic random-access memory ( DRAM ) manufacturers ( Intel, Micron, Samsung, SK hynix, and TSMC) are building and expanding in the United States. In contrast, no other country’s economy has more than two of these factories working there…

The United States is projected to produce at least 20 % of the world’s leading-edge logic chips by 2030 (up from zero percent in 2022 ) and ~10 % of its leading-edge DRAM chips by 2035 ( also up from zero percent ) —both technologies that are essential to the future of artificial intelligence ( AI), high-performance compute, and advanced military systems. For the first time in nearly a decade, a new factory in Arizona has begun producing these technologies domestically. This is the first time in almost a decade that a new factory has done so.

And The Economist, certainly no friend of industrial policy in general, has  , grudgingly admitted , that US reshoring of the semiconductor industry is succeeding:

Early returns are impressive: the]CHIPS Act ] programme has catalysed about$ 450bn of private investments. And this money is spread across much of the industry, from high-tech packaging to memory chips. The most advanced chips, which are less than 10 nanometers in size, are a key indicator of success. In 2022 America made few such chips. By 2032 it is on track to have a share of 28 % of global capacity.

Foreign direct investment, especially from Taiwan’s TSMC, has been significant in the case of US auto manufacturing a generation earlier.

In early 2024, some poorly informed pundits were writing stories declaring that” DE I killed the CHIPS Act”, while , others were wondering , whether Americans had a culture capable of making chips. Those articles were spectacularly ill-timed — obstacles were quickly overcome, and the factory is now , pumping out 4nm chips. Those are, by at least some measures, the most advanced semidconductors ever made on American soil.

And what’s more, those chips are being made with yields ( i. e., quality ) that are  , comparable to, or even higher than, what Taiwanese factories get. The notion that American workers couldn’t produce high-quality goods proved to be incorrect.

The cost of the chips made in the US is a little higher ( about 30 % more right now ), but that price difference will likely decrease as the demand increases and the chipmaking experience spreads throughout the nation.

In fact, the reshoring effort is going so well that TSMC is , now planning , to build even more cutting-edge chips at its US plants:

The effort to reshore semiconductors has so far been a huge success.

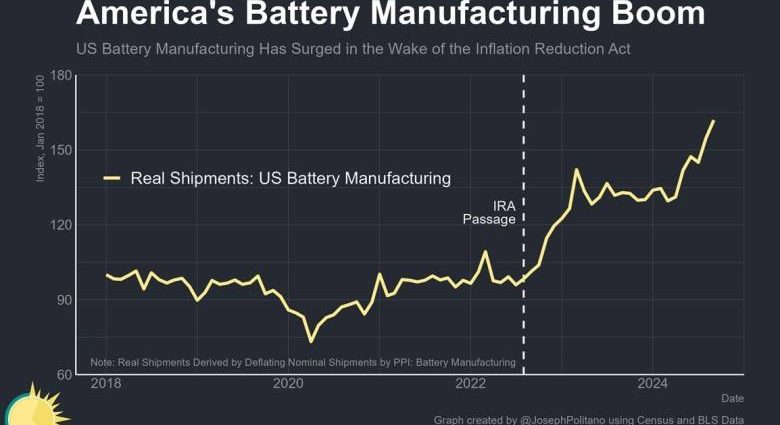

Batteries , look like a third reshoring success. Currently, most batteries are produced in China, but the Inflation Reduction Act may be , starting to turn things around:

It’s not just factories being announced, either, production in the US is way up:

The reshoring of the solar, chip, and battery industries is direct criticism of the critics and evidence of American manufacturing’s viability.

Although these are only three different types of industries, they will undoubtedly facilitate the reshoring of those that are either producing these manufacturers or using their own resources. American reindustrialization isn’t just about a few key tentpole industries — it’s about a whole web of suppliers, customers, related industries, and talent.

Fortunately, we can already see this web starting to form in the US SEIA , reports , that America’s solar manufacturing boom isn’t just limited to the panels themselves, but related industries like solar tracker, solar inverters, and upstream materials production like wafers and ingots.

Meanwhile, the CHIPS Program Office , reports , that the semiconductor boom also includes downstream activities like packaging and testing. The Economist , points out , that this ecosystem, as well as the talent that gets developed for the CHIPS Act’s projects, will reduce costs and help sustain future expansion of chip manufacturing in America:

The subsidies have reduced the cost of building and running fabs in America by about 30 % compared to those in Asian nations. Because Asian governments give companies more money, their costs are lower in part.

However, Asian producers have also benefited from dense manufacturing clusters, which have well-trained workers and a large supply chain nearby. The goal is that CHIPS in America has initiated this process. ” It’s enough to get the flywheel going”, says ]outgoing Commerce Secretary Gina ] Raimondo.

Currently, it is largely a matter of political will and decency whether reshoring continues. If Donald Trump continues to criticize the solar industry or follows through on his previous threats to revoke the CHIPS Act, production could significantly shift back to China.

It would be ironic if a president who came to power and promised to revive American industry ended up being the one who put an end to our industrial revival.

This article was first published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack and is republished with kind permission. Become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.