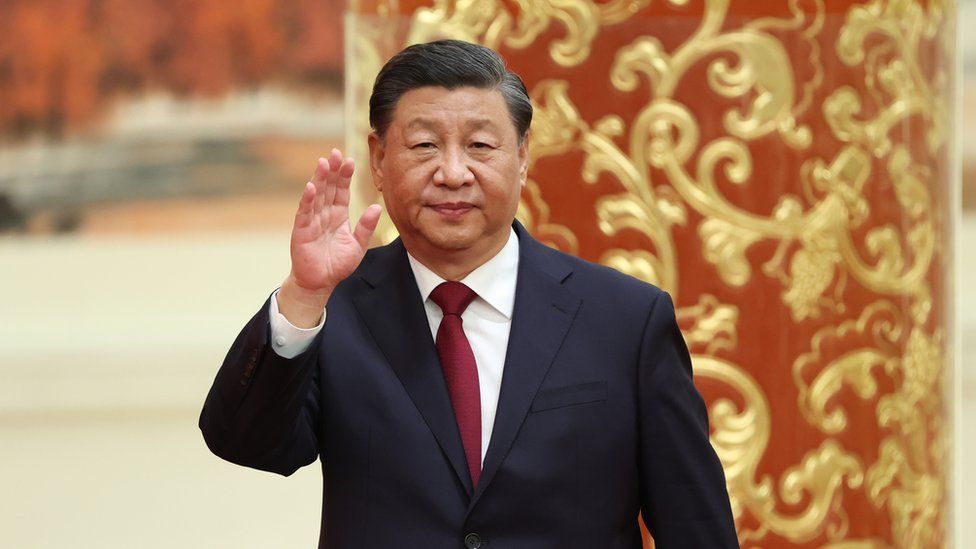

The National People’s Congress, which starts this weekend, will be the symbolic culmination of Xi Jinping’s epic power grab.

China’s leader has overhauled the Communist Party placing himself at the core and nobody else has even a remote chance of challenging him.

The starkest representation of this will be in the shift in personnel to be announced at the annual political meeting, a rubber-stamp session of nearly 3,000 delegates.

Take the role of the premier, the person managing the world’s second-largest economy and, in theory, second only to Mr Xi in the power structure.

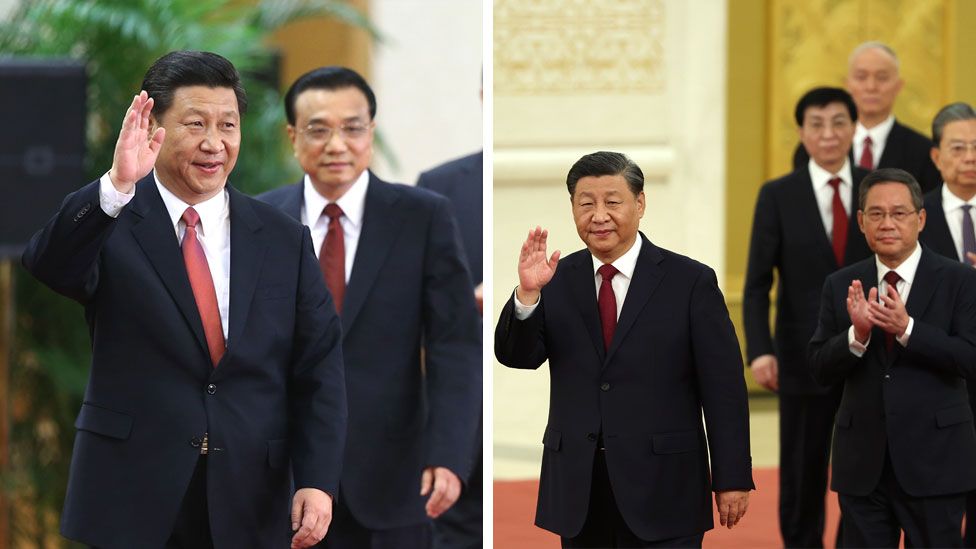

Outgoing premier Li Keqiang will take centre stage on day one. Then, at the end, a new premier, almost certainly Li Qiang, will occupy the limelight.

They’re two very different people, especially in terms of their loyalty to Mr Xi, who started an upheaval a decade ago with his anti-corruption crackdown, cutting a swathe through the ranks of rival party factions.

At last October’s Communist Party Congress, new appointments to the seven-man Politburo Standing Committee meant the most powerful group in the country now had only Xi loyalists.

At this gathering, it is the heads of various departments and ministerial positions which will be replaced. They are all expected to fall into the same camp.

It doesn’t mean they are not qualified but will they be prepared to offer fearless and frank advice to the man who put them there?

“On the one hand this might mean Xi can really get things done with his new leadership but, on the other, there is a danger of him being stuck in an echo chamber,” an experienced business figure told the BBC.

So, what will these appointments mean for China’s direction?

If Li Qiang is indeed the new premier, sitting up there on the last day of the NPC, taking screened questions at the annual press event, it will have been a meteoric rise for him.

As Shanghai party boss, he oversaw the disastrous two-month lockdown of China’s financial capital last year.

For this reason, many were surprised when he was promoted to become number two in the Communist Party pecking order.

It wasn’t so much that there had been a lockdown but how poorly it was managed. Confining delivery drivers to their homes meant food and medicine could not be transported efficiently to many millions of people who were not allowed outside.

There were serious food shortages and, when deliveries did get through, residents posted pictures of the rotten vegetables they were supposed to survive on.

Towards the end of the city-wide shut down people had had enough. They were kicking down the fences put up to restrict them and fighting with the guards put in place to enforce what was by then the much hated zero-Covid approach.

Observers have questioned how the person in charge of this massive logistical failure could be given the job of running the entire country.

Well, for one, his past paints a different picture. In years gone by, some in the business community saw him as an innovator who was able to get around Party rigidities.

“He’s smart and he’s a good operator but he definitely got the job because of his loyalty to Xi. When the president asks him to jump, he responds, ‘how high?'” says Joerg Wuttke, the president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China. He has been doing business in the country since the 1990s and has had dealings with the upper echelons of the Communist Party for years.

Mr Wuttke added that the negative impact of the zero-Covid strategy is still being felt by businesses and ordinary consumers alike.

“There is caution where spending is concerned because of the trauma of the zero-Covid period,” he says, “People have been shell-shocked by the last few years in China. They are wary of taking risks and are very careful when making decisions.”This trauma is especially present in Shanghai and the allure of that city has faded considerably when it comes to foreign investment.”

However, Mr Wuttke doesn’t think this is solely Li Qiang’s fault – and other businesspeople echo the sentiment.

Li Qiang is credited with bringing Tesla to Shanghai. It was the company’s first factory outside of the US and it was allowed to set up its own venture, without the requirement of teaming up with a Chinese partner in the same way that other foreign car companies had been made to do.

In trumpeting the virtues of Shanghai’s pilot Free Trade Zone in 2019, he said it would become an area open to international competitiveness, which would “work as an important carrier for China to become deeply integrated with economic globalisation”.

He is seen in certain circles as a more liberal figure who’s prepared to bend the rules.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Yet, it’s unclear whether he will now be an empowered rule bender, not afraid to do what has to be done because he has Mr Xi’s backing, or a former pragmatist who will fall into line on a much larger stage, just inside Mr Xi’s shadow.

Back in 2016, he became party secretary for the wealthy eastern province of Jiangsu, known for its tech companies. He sought out meetings with Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma and other executives seeking advice on the climate for business there.

But that was a different time. In recent years, Mr Xi has ordered that tech companies be reined in, believing that they had become too powerful for their own good. It has been common for the heads of these companies to “disappear” so they can be questioned by the Party’s discipline inspection officers – the latest being billionaire banker Bao Fan who brokered key tech deals.

This doesn’t seem like the type of thing that Li Qiang would have encouraged in the past, but he and Mr Xi go back a long way.

Before he was in Jiangsu, he was based to the south of Shanghai in another wealthy eastern province, Zhejiang. At that time the provincial party chief was one Xi Jinping and, after Li became his chief of staff, the two would work late into the night, impressing those above them.

Mr Xi never had such a shared background with outgoing premier Li Keqiang.

They rose together during a period with a much more collective leadership and Li Keqiang was then, in a way, a rival. He was also being considered as a candidate for the top job. You can’t help but wonder what China would be like now if he had succeeded instead of Xi.

A bright economist who graduated from Peking University just after the Cultural Revolution, Li Keqiang rose through the ranks of the Party via the Communist Youth League, a rival power bloc.

After missing out on the top job, he was soon being constrained as premier under Mr Xi who was running the place with a reach not seen since Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China.

At one point as premier, Li Keqiang declared that the re-introduction of street vendors in cities across China might help reinvigorate the economy and create a more lively atmosphere. But those who answered the call in Beijing were soon being ordered away again by the police.

Under Mr Xi, what makes the capital look “backwards” or “old fashioned” is to be frowned upon. It didn’t matter that the premier no less had suggested this. In Beijing, it wasn’t going to fly.

Li Keqiang was seen to be aligned to former leader Hu Jintao, who was taken off stage at last year’s Party Congress on Mr Xi’s orders.

Whether this was because Mr Hu was ill or he was causing trouble after his people had been overlooked for promotion, this still unexplained event brought the curtains down on a previous era in front of the world’s cameras.

As he was being led away, he tapped Li Keqiang on the shoulder in a friendly gesture and the premier nodded back.

Li Keqiang will be remembered for strong economic track record but the end of his time in office was mired in zero-Covid crisis.

During the worst of it, he said the economy was under massive pressure and called on officials to be mindful of not letting restrictions smash growth.

But, when cadres had to choose between his order to protect the economy and Mr Xi’s to maintain zero-Covid with extreme discipline, it was no contest.

Nothing trumps Xi Jinping, who now has the party lined up the way he wants it.

The only danger he seems to face is that his reputation has taken a hit among sections of the general public.

Zero-Covid; the rushed abandonment of zero-Covid on he back of widespread protests; the property crisis; high youth unemployment; the tech crackdown and the huge damage to the service industry have all hurt his standing.

“Mao survived during a time of complete economic collapse when people didn’t have that much to lose,” Mr Wuttke says. “Now people have a much-improved standard of living but middle-class parents are starting to worry that their kids won’t have a better life than them.”

This year’s NPC, and especially those who are elevated at the meeting, will be watched closely by those who want to see where this economic powerhouse is heading.

If the way of Mr Xi is all it’s cracked up to be, China should be firing on all cylinders soon now that all impediments to the leader’s will.

If the country is not performing well on all fronts, that’s when the difficult questions will start to emerge.

Related Topics

-

-

23 October 2022

-

-

-

17 October 2022

-

-

-

10 October 2022

-

-

-

1 June 2022

-