Getty Images

Getty Images After a decade of scepticism over free of charge trade deals, India has been signing the bevy of new contracts with a number of nations to reduce trade barriers, eliminate tariffs and gain preferential access to global markets.

Earlier this year, the nation brought into pressure a comprehensive economic collaboration with the UAE and signed an ambitious trade pact with Australia, committing to reduce tariffs by 85%. Advanced negotiations are also under way to sign free trade contracts (FTAs) with the UNITED KINGDOM and the EU.

These deals are expected to pay a range of products and services through textiles to alcohol, automobiles, pharmaceuticals along with subjects like work movement, intellectual real estate enforcement and information protection.

Getty Images

Indian and UK officials work “intensively” to conclude the “majority of talks on a comprehensive plus balanced FTA by the end of October 2022”, the UK said in the statement last week.

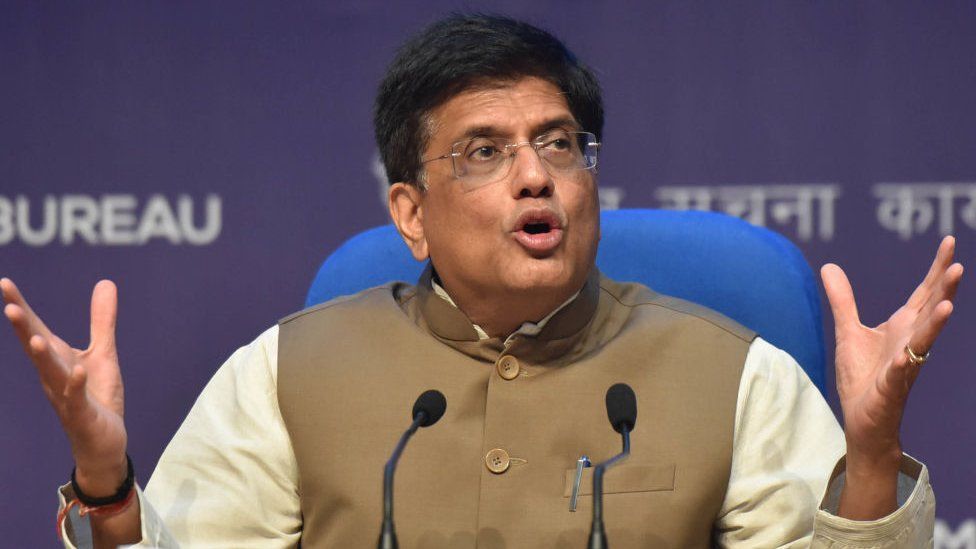

The re-launch of FTA negotiations using the EU after a protracted wait was reflective of a “new Indian which wishes to engage with the developed planet as friends, from a position of fairness”, India’s Trade Minister Piyush Goyal said last month.

This renewed zeal marks a sharp departure from India’s trepidation about trade liberalisation over much of the final decade.

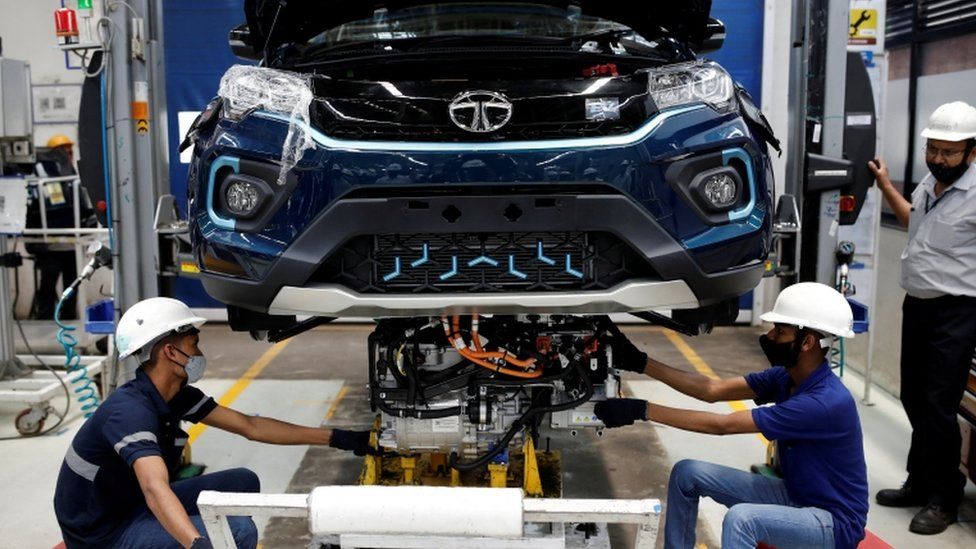

Within 2019, India once pulled out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), touted to be the world’s largest business agreement between Tiongkok and 14 some other Asian countries, after being part of the negotiations with regard to seven years.

Delhi was worried that the agreement would certainly reduce duties on imported goods simply by 80-90%, and further widen India’s large industry imbalance with Tiongkok, exposing domestic makers to greater foreign competition.

Getty Images

The government’s assessment of India’s current FTAs and preferential trade pacts isn’t favourable either.

According to NITI Aayog, the public policy think tank of Indian, while bilateral business with partner nations like Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN region increased following a signing of industry deals, imports increased more sharply compared to exports, leading to “unfavourable gains” to India’s trade partners.

Which explains why India’s approach now is to achieve a “fair and balanced” FTA with complementary financial systems, focused less upon competition and more on collaboration, according to Mr Goyal.

But achieving this balance might be easier said than done.

In Akluj in Maharashtra state in western India, Fratelli, one of India’s greatest winemakers, has been making wine for the last fifteen years.

Gaurav Sekhri, who co-founded the brand, says the company has been increasing at 30-40% over the last couple of years, as Indians start to develop a flavor for wine.

Getty Images

Yet as India fast-tracks free-trade negotiations along with countries like the UNITED KINGDOM and the EU, he is worried about more competitors from cheaper, brought in brands, just as the particular sector is over the cusp of growing old.

Mr Sekhri expects the UK and EU deals to be similar to the FTA signed with Australia where responsibilities on wines more than $5 have been decreased from 150% to 100%, with additional phased reductions within the next decade.

He says the industry needs some protection since consumers will be more likely to choose non-Indian wines of the same cost as they are recognized to be of quality.

“Also the life of our own vineyards is lesser compared to European vineyards. And for that reason alone our costs will be higher and protection will be necessary, ” adds Mr Sekhri.

Getty Images

Yet opposition to business liberalisation is moderate.

Textile plus apparel firms, which usually recorded the highest ever exports in the last monetary year, are encouraged by the prospect associated with lower tariffs on their goods.

Mumbai based Milaya Embroideries, which produces clothes for global style brands like Dolce and Gabbana plus Emporio Armani, is currently hit by a dual whammy of tariffs – while adding raw material from Europe and while transferring finished clothes to the continent.

Apparel manufacturers are also losing business in order to countries such as Vietnam which recently ratified its FTA with all the EU. For them, the particular imperative to act is usually greater.

“It’s much cheaper for Western companies to place purchases with Vietnamese suppliers because they don’t have to pay out duties. Whereas responsibilities are between 9% and 16% intended for imports from India. I think we will see lots of demand from the customers if the duty prices are slashed, inch said Shashank Jain, COO of Milaya Inc.

For India and its partners, the reasons behind the renewed interest in these types of trade talks are usually as much strategic as they are economic.

India’s annual merchandise exports crossing the $400bn mark in the last financial year – a 40% annual jump – has decreased “the hesitation around giving additional market access”, said Biswajit Dhar, a professor at the Centre to get Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

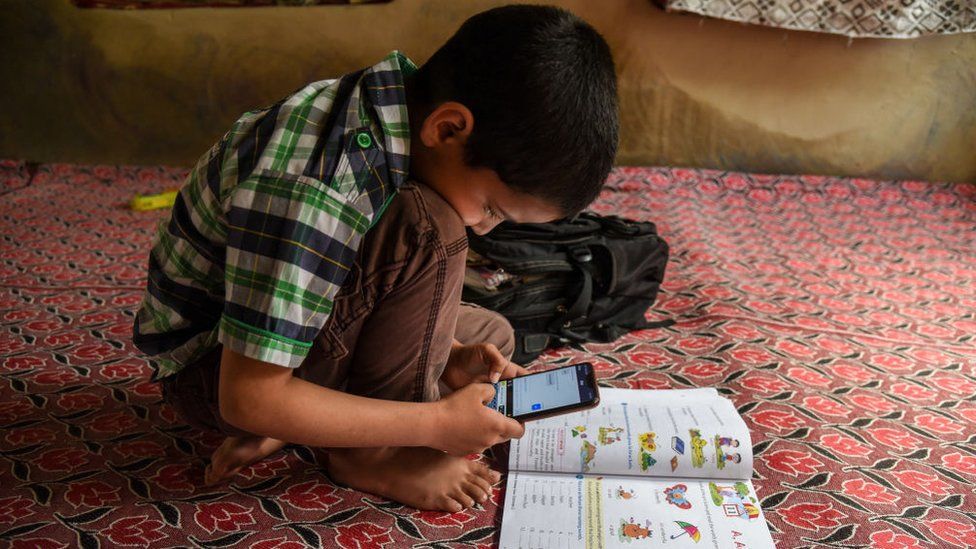

But equally, as countries such as Britain look to expand supply chains for the Indo-Pacific in a post-Brexit world, and worldwide firms adopt a strategy in which they avoid investing only in China and diversify their businesses in order to alternative markets, Delhi has been presented with an unusual opportunity to become internationally integrated.

Amitendu Palit, a senior analysis fellow at the Nationwide University of Singapore, says increased collaboration between countries like India, Australia, The japanese and the US reveal their growing stress over China’s control over supply chains as well as its ability to disrupt them.

But experts can also be concerned about the “dichotomy” between India’s FTA strategy and its general trade policy.

“(The) new-found excitement for FTA seems to conflict with its trade-policy stance under the self-reliant India initiative, in whose genesis is upon “vocal for local”, thereby promoting locally produced goods over imported goods, ” researchers Surender Singh and Suvajit Banerjee recently wrote within the journal Economic and Political Weekly.

Getty Images

Indian has undertaken more than 3, 000 tariff increases which has affected 70% of imports, according to Arvind Subramanian, former economic agent to the government.

This “lack associated with synergy” between industry policy and FTA strategy “not just weakens India’s negotiating capacity, but also undermines the potential economic advantages of free trade, ” Mr Singh and Mr Banerjee say.

Ironing out there these inconsistencies will be of essence. The particular timing will be crucial as well.

The timelines set to conclude these types of deals are impressive. India can sick afford to lose the pace because by middle of next year, the election cycle will get under way.

“Once you already know momentum, it can be lengthy drawn, ” alerts Mr Dhar.

More on this particular story

-

-

30 October 2020

-

-

-

7 December 2021

-