Excellent investigative report has been produced by Viola Zhou into the tensions and growing symptoms at the TSMC shop in Phoenix, Arizona.

Before I tumble in, but, I should note that in my opinion, the article that the newspaper gave to this article was not very representative of what’s really going on. Although the plant’s headline reads” TSMC’s debacle in the American desert,” it does n’t currently look like it.

Output at the TSMC factory was scheduled to start in 2024. Most , sources , — including Zhou’s post — say that time has been delayed until 2025. However, some and recent  reports  claim that the manufacturer is now , ahead , and may begin manufacturing in 2024:

Today, according to a , a report from the Taiwanese news outlet Income. udn, TSMC is expecting to start aircraft manufacturing operations by late- April, with the preparations for mass manufacturing to be completed by the end of the year. Whether both fabs or just the 4 nm service are scheduled to start producing sooner than expected is a mystery.

The more positive reports emerged quickly after the anticipated subsidy was given, suggesting that TSMC was merely sandbagging to ensure they received their CHIPS Act funding. It’s still not very apparent which times are right, and the company itself does not know.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that there was a lot of hubbub in a dispute between TSMC and the Arizona construction organizations in the middle of 2023. A few months later, however, a resolution was reached and the debate vanished.

There’s a very good chance that this title turns out to be anxious and early, even though calling the TSMC’s Arizona task a “debacle” might garner a lot of attention from those who are ideologically invested in either the US’s failure or its success.

That having been said, yet, the real monitoring in the content is excellent. The conflict between TSMC’s work culture and the American workforce is illustrated by a number of narratives. Just a few examples, please:

The American engineers complained of rigid, counterproductive hierarchies at the company, Taiwanese TSMC veterans described their American counterparts as lacking the kind of dedication and obedience they believe to be the foundation of their company’s world- leading success … “]The company ] tried to make Arizona Taiwanese” ,]said ] G. Dan Hutcheson, a semiconductor industry analyst…

According to TSMC executives, an intense, military-style work culture is the key to the business’s success, according to Rest of World. Professionals have 12-hour days off and occasionally weekend off. Chinese commentators joke that the business runs on engineers with” slave mentalities” who” offer their livers” — local slang that underscores the intensity of the work…TSMC’s work culture is extremely demanding, even by Japanese standards. Previous executives praised Taiwan’s tight work ethic, the Confucian culture, and the respect for authority as key factors in the company’s success…

In front of their classmates, managers often made the suggestion that American workers quit engineering… ” It’s hard to get them to perform things”, a Chinese expert in Phoenix]said].

Stories like these inevitably sway stereotypes: stupid Americans who want to be coddled and praised versus hard-working, polite East Asians. And this further fuels the conceit that the US ca n’t compete with East Asian nations for high-tech manufacturing, or for manufacturing chips.

But there are many factors to fear this conclusion. First of all, Americans ‘ concerns about Chinese device manufacturers are very similar to those they had about Japanese companies in general in the 1980s and first 1990s. However, even in some manufacturing sectors, Japanese management emerged as bulky and ineffective.

East Asian management culture does n’t always succeed

In some manufacturing sectors, including cars and electronics, US companies struggled to compete with Chinese companies from the late 1970s until the early 1990s. A number of academics, including Richard T. Pascale and W. Edwards Deming, attempted to examine Chinese management practices for insights that American companies could use.

But some observers, like , Ezra Vogel,  , Robert Christopher, and even , Akio Morita of Sony, claimed that Japan’s performance on manufacturing stemmed from heavy- embedded cultural values of difficult work, respect for authority, etc — very similar to the Chinese cultural values attributed to TSMC by Viola Zhou’s interviewees.

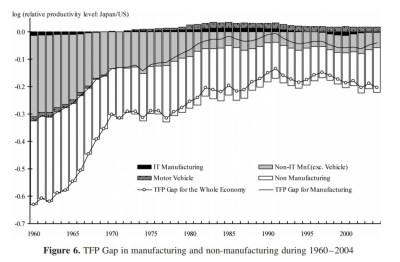

It did n’t work out that way. Japan’s labor productivity lag significantly behind that of many other wealthy nations at the beginning of the 1990s. In 2007, economists Dale Jorgenson and Koji Nomura did , a detailed industry- by- industry accounting , of productivity differences, taking differences in capital investment into account ( when you do this, it’s called Total Factor Productivity ). Around 1990, they discovered that Japan’s manufacturing productivity almost doubled that of America; this resulted in a reversal of this trend.

When they broke things down by industry, they found that although Japan did beat the US in some industries, this outperformance sometimes reversed itself over time:

In the 1990s, Japan established itself as a leader in the manufacturing of motor vehicles. However, it lost ground in terms of computers and electronic components, and its advantage vanished in terms of machinery in the 1990s.

There are many things that go into TFP — technology, resource costs, regulation, clustering effects, trade, and so on. We ca n’t simply say,” Oh, Japanese management culture was n’t that good after all.”

However, it’s worth noting that many analyses of Japan’s current, stagnant productivity now explicitly attribute this to an office culture that is not productive! Working for a Japanese company means long, unproductive hours at the office, trying to look productive for , elderly, entrenched managers.

Useless, overwork is a practice known as “presenteeism,” which prevents employees from getting enough sleep and makes them slow and unmotivated. In addition, I’ve personally seen instances of this in Japanese universities, and my Japanese friends ‘ companies have many similar tales.

This does n’t mean the cultural essentialists of the 1980s were necessarily wrong. In fact, it’s possible that the same principles of work for work’s sake and respect for corporate hierarchy that were once attributable to Japan’s manufacturing competitiveness now prevent work to be done in a white-collar environment.

We ca n’t simply apply the lessons learned from one nation to another because Taiwanese management culture is different from Japanese management culture. But here’s another interesting example. Stan Shih, the founder of Taiwanese multinational Acer, predicted that US PC brands would vanish in 20 years.

According to the Taipei-based Commercial Times newspaper,” the trend for low-priced computers will continue over the next few years,” said Stan Shih, the founder of the island’s top personal computer brand.

” But US computer makers just do n’t know how to put such products on the market … US computer brands may disappear over the next 20 years, just like what happened to US television brands”.

Since Shih only has six years left, it seems like only 14 have passed. However, the top three US PC manufacturers still held a 45.4 % market share as of late 2023, compared to the top three brands combined, China and Taiwan, for which Acer was only 6.4 %:

The East Asian electronics cluster is formidable but not invincible. Viola Zhou’s account of TSMC’s history suggested that the company’s management culture is n’t quite as effective as you might think:

Several former American employees argued that only if the tasks were worthwhile to complete, and that they were against longer working hours. ” I’d ask my manager’ What’s your top priority,’ he’d always say’ Everything is a priority,'” said another ex- TSMC engineer. So many times,” so, so, so, many times, I would put in extra hours to finish something,” I thought.

Additionally, the Americans objected to Taiwanese colleagues ‘ unjustifiable tardiness at work. ” That pisses me off” ,]former TSMC engineer ] Bruce said. They were” just doing it for show,” the statement continued.

Five US employees admitted to telling a newspaper, Rest of the World, that TSMC engineers occasionally fabricated or fabricated customer or manager data. Sometimes, the engineers said, staff would manipulate data from testing tools or wafers to please managers who had seemingly impossible expectations.

One engineer once said,” Anything they could do to get work off their plate, they would do,” “because the workers were spread out so thin.”

Four American employees compared TSMC culture to” save face,” where employees strive to improve the appearance of their teams, departments, or organizations while sacrificing productivity and employee wellbeing.  , Pointless busy work just to please the boss? I’ve heard that story before, I guess.

High Capacity blogger Kyle Chan had some intriguing thoughts on the subject:

]Viola Zhou’s ] story provides a much- needed counterpoint to the narrative that” Asians simply work harder. Everyone else is “lazy” all the way. It’s easy to equate a set of cultural practices that appear to be “hard work” with actual performance, despite the fact that I have no doubt that TSMC is largely responsible for its success thanks to its extraordinarily hardworking employees.

Publicly shaming your employees, restricting contact with family and listening to music, churning out endless PowerPoints and weekly work reports, forcing American staff to somehow understand instructions in Mandarin. Although these business practices may seem like they’re incredibly difficult, are they actually effective?

We all knew that good managers did n’t stay in the office late at night when I was in my consulting days. The good managers did n’t have junior staff put in” face time” and pull all- nighters to make slides that ended up getting deleted. The competent managers understood when to sprint and how to convey to the team that their work was important…

The fact that Taiwanese employees are so eager to work for TSMC is one of the key factors in why they are so eager to do so [. ]

Which brings me to my next point.

Macroeconomics or management?

One of the most prosperous companies in the world is TSMC, a true national champion and a significant advance in industrial policy. But there are a number of reasons why its success relative to American chipmakers, as well as its struggles in the US market, might depend on economic factors outside the company and unrelated to Taiwanese culture.

First of all, much has been made about how TSMC surpassed Intel, Samsung, and other chip manufacturers who create and manufacture their own chips in-house.

This success is typically attributable to TSMC’s “foundry” model, which allows it to specialize in the manufacturing process and cross-apply techniques and lessons from one type of product to another. Instead of making its own chips, it makes everyone else’s chips.

But you know who else ca n’t make chips as well as TSMC? Any other Taiwanese business that is active today. It’s just TSMC towering over the rest of the others in a chart of revenue for chipmakers in Taiwan:

Only 30 % of TSMC’s revenue comes from competitors, who also make 30 % of its revenue. No one is discussing whether the US would launch a war to protect Nuvoton from a Chinese invasion in Arizona or about building Winbond factories there. Unlike Japanese auto companies in the 80s, or even Taiwanese PC makers in the 2010s, there is precisely , one , top chipmaker in Taiwan.

In terms of skill and work ethic, TSMC pretty much picks Taiwanese talent. If you’re a top Taiwanese chip engineer, TSMC is where you work, but other companies do n’t. So the engineers at TSMC are n’t representative of Taiwanese skills and work ethic as a whole, they’re a special, hyper- selected elite.

Additionally, TSMC does n’t have to pay a lot for these elite performers. The median salary at TSMC was US$ 64, 874 in US dollars in 2021, with a bonus of US$ 40, 000, or roughly$ 105, 000.

In the tech world, that’s nothing. A starting-level American software engineer working for Visa, the credit card company, earns less than that.

Why do TSMC employees have such high salaries? Well, one big reason is that Taiwanese workers just do n’t make very much in general. The typical pay for full-time employees in Taiwan is$ 22, 242. In Missouri or South Dakota, that’s less than a worker making the minimum wage. So in Taiwan, a TSMC salary is fairly big bucks.

Why are Taiwan’s wages so low? Taiwan is poorer than the United States, for one reason. Another reason is that Taiwan makes sure to , keep its currency very cheap , relative to the US dollar, probably in order to improve the competitive position of companies like TSMC.

In addition, TSMC’s Arizona fabs must compete with other American tech companies for talent. Chip companies pay a bit less than what TSMC employees in Taiwan, but typically between$ 200,000 and$ 30,000 for hardware engineers at Apple. But it’s not just the hardware industry TSMC has to compete with in America, it’s the , software , industry too.

The skill set is similar to what a smart young American would be if they wanted to learn either how to write code or how to build chips. And they typically get paid more if they choose to write code. A typical software engineer at Google will get paid around$ 300k-$ 400k, for Facebook , it’s more like$ 300k-$ 500k. Try naming a Taiwanese software company in the meantime.

And do n’t make up for it: The best American actors frequently put in a lot of effort. High earners in America , work hard in general, and many top people are putting in those 70- hour workweeks. Many young lawyers and doctors practice this, as do Tesla’s and other tech company founders and new hires.

Under Andy Grove’s leadership, Intel had an intense, punishing work environment, similar to TSMC. But they have to have some special motivation in order to do this — either the promise of a very high salary, or the promise of a big exit for their startup, or at least the pride of working as a doctor or for a prestigious company like Tesla. TSMC is well-known in America, but it lacks that prestige in Taiwan.

According to Zhou’s article, Taiwanese workers in the United States are drawn to better jobs elsewhere.

An engineer, who has worked at both Intel and TSMC, said Taiwanese colleagues had also asked him about vacancies at Intel, where they expected a better work- and- life balance.  ,

At its Arizona factories, TSMC is actually competing against that. It’s having to pay a multiple of what it would pay in Taiwan, for workers who are less elite and less passionately committed to the company.

Taiwan’s management or culture have no business doing this, it’s just that Taiwan is a less wealthy nation than America, and it has chosen to integrate many of its best people into a single national champion organization. In addition, it will cost more to make chips in Arizona, of course.

Americans can learn East Asian manufacturing methods just fine

I’ve argued that:

- Even if East Asian management culture appears to be very intense, hard-working, and not necessarily the best, it is not.

- TSMC’s cost disadvantages in Arizona depend on macro factors, not just on cultural differences ( or perhaps not on cultural differences at all ).

However, East Asian businesses occasionally come up with significant management innovations that actually increase productivity significantly. However, when they do, American workers can learn from and use those innovations in America.

The prime example here is the Japanese car industry. Japanese automakers started producing significantly more cars in the US in the 1980s as a result of significantly fewer exports from Japan:

Every Japanese carmaker has a number of sizable US auto plants, and many of its most famous American models are produced by workers for Japanese companies.

This was an absolutely massive experiment in foreign direct investment by an East Asian country into the US. The Japanese companies had a lot to teach their American workers because their auto manufacturing productivity was significantly higher at the time.

And instruct them, as they did. American car plants adopted practices such as the kanban scheduling system, the kaizen system of continuous improvement (originally conceived of in the US but put into practice in Japan ), and many others.

These methods are primarily derived from the well-known Toyota Production System, but they are also the foundation of what is now known as lean manufacturing. These methods were first used by Japanese automakers in America, but they have since been widely used in many other sectors of corporate America as well.

American factories were successfully able to learn these Japanese management techniques. There are only a few discernible differences between Japanese and American vehicles, according to detailed comparisons.

And despite America’s uncompetitive exchange rate, the cars produced by Japanese brands are still highly competitive abroad. Consumers in Korea are  , buying Nissan Altimas , made in Tennessee and , Honda Accords , made in Ohio. Toyota Highlanders, manufactured in Indiana, are being purchased by Australians.

It seems a safe bet that American workers can learn to build chips like Taiwan if they can learn to build cars like Japan. But Japanese carmakers started trying to teach American workers their tricks in the late 1980s, TSMC has barely started trying. According to Viola Zhou’s article, TSMC is not even capable of talking to American workers:

Nearly all communication at Fab 18 [in Arizona ] was conducted in Taiwanese and Mandarin Chinese. Technical terms and images were hard to decipher.

One American engineer attempted to translate documents by copying Chinese text into a handwriting recognition program because Google for employees was prohibited from uploading work documentation to the site. It was n’t very effective because managers turned down Americans ‘ participation in higher-level discussions held in Mandarin…

Language barriers are the very earliest thing that companies have to overcome when they build factories overseas. It’s still very early to say that TSMC ca n’t even communicate in English.

It’s absurd to claim that TSMC’s American factories are a “debacle” just because there was a small delay at the beginning is irrelevant. Foreign direct investment is a long, winding, arduous journey. It’s not the kind of situation where we should anticipate that everything will work out flawlessly the first time.

However, challenges like this one are not viewed through the mystique of East Asian culture. Cross- country cultural differences are real but they are n’t as impactful on business as people like to think. Humans have the ability to learn.

This article, Noah Smith’s Noahpinion, was originally published on Noah Smith’s Substack, and it is now republished with kind permission. Read the , original and become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.