Varinder Chawla waited with bated breath at a helipad in Alibaug, a coastal town about 96km (60 miles) from India’s financial capital, Mumbai city.

Through his sources, he had learnt that Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan might catch a helicopter from there to head to his palatial home in Mumbai.

It was 2 November 2022, Khan’s birthday. The star always greeted the thousands of fans who gathered outside his home to wish him well on the day. Chawla was sure Khan wouldn’t disappoint them, so he waited patiently.

Finally, a car approached with Khan inside. Chawla gestured at the actor and he waved back; so, he hit the button. Click.

“That was a real money shot. My efforts paid off,” Chawla says.

He is among Bollywood’s growing crop of paparazzi who do all sorts of things to snap celebrities in candid moments: follow them on bikes, befriend their managers and drivers to get tip-offs about their whereabouts, hang around airports and restaurants, and even memorise stars’ vehicle registration plates to track them.

The paparazzi share a “co-dependent relationship” with Bollywood’s celebrities, says Mandvi Sharma, a former publicist for Khan, who now runs her own public relations company.

Stars rely on them for publicity and they depend on stars to make a living. But this relationship can also turn toxic, and observers say that the dynamic is changing in the era of social media.

In February, actress Alia Bhatt criticised photographers for taking pictures of her in her living room, calling it a “gross invasion” of her privacy.

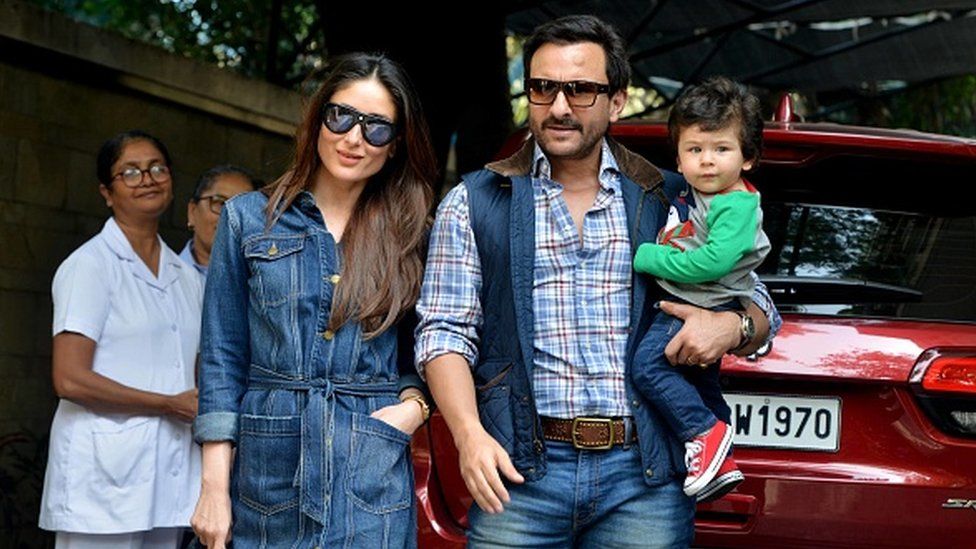

Earlier this month, actor Saif Ali Khan made headlines after he sarcastically told the paparazzi to “follow him into his bedroom too” after they followed him and his wife, Kareena Kapoor Khan, into their building.

The video appeared on the Instagram account of Viral Bhayani, a popular paparazzo, and has since been shared widely on social media.

In 2019, Saif Ali Khan had said that he found the paparazzi stationed outside his house, waiting for a shot of his child, “disturbing to say the least”.

Manav Manglani, who has been a paparazzo for about two decades and now has 15 photographers working for him, says that social media has created an insatiable appetite for celebrity content.

A couple of decades ago, it was only newspapers and magazines that bought photographs from the paparazzi.

Things changed dramatically in 2015 with the influx of digital media in India, as media and celebrities learnt to leverage social platforms for work, Sharma says. “It became a huge publicity gamut.”

Today, Manglani says paparazzi have to cater to scores of platforms which millions of Indians use for updates on their favourite celebrities.

“We’re shooting, uploading, posting, sharing stories or live streaming on multiple apps like Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Roposo and Snapchat,” he says.

In fact, many of the well-known paparazzi share content on their hugely popular Instagram accounts – Bhayani has 5.2m followers, Manglani has about 2.6m and Chawla 1.3m.

Muddying the waters are amateur photographers and YouTubers who are also trying to cash in on the demand.

Chawla agrees that sometimes, “boundaries get crossed” in the heat of the moment, as everyone competes to get the best or most exclusive shot. But he says he avoids posting content that would offend anyone.

Anita*, a former photographer, said she found paparazzi assignments stressful and even traumatic at times. “If I missed a shot that someone else got, my boss would yell at me,” she says, and adds that generous tips would be given to those who did get the exclusive click.

Pressure also comes from news agencies and TV channels who ask for the photos and videos they see on rival platforms, Manglani says.

Things were very different up until the 1990s. Chawla, whose father was also a celebrity photographer, remembers accompanying him on the sets of films, where he would be invited by a star’s manager to take promotional photographs.

“We would eat dinner or lunch on the set with celebrities; we got to chat with them and friendships developed. Actors would take a break from shooting and pose for photographs in multiple costumes,” he says. “There was no ‘paparazzi culture’ at the time”.

Ranjona Banerji, an independent journalist who writes on the media and politics, says that the 90s ushered in change as India opened its doors to the world.

“The proliferation of private TV channels sowed the seeds of wanting more – more entertainment, more information,” she says, and adds that film magazines like Cine Blitz and Stardust also became bolder in their coverage of celebrity gossip and news.

“Celebrity photographs no longer had a staged look and feel; they became more candid and casual,” she says.

At the same time, Bollywood was becoming increasingly corporatised. Banks and studios began financing films, and stars – who generally had a single public relations officer – now began being handled by PR teams.

“This has created a strange kind of distance between celebrities and photographers,” says Chawla. “Though we still have access to them, perhaps more than before, we’ve lost out on the warm friendships,” he says.

The paparazzi culture emerged in India possibly in the mid-2000s.

Chawla says he started the trend by sneaking a photo of Abhishek Bachchan on his wedding day, as photographers had been banned from the venue. Yogen Shah, a veteran paparazzo, credits himself with starting the trend, when he took pictures of celebrities exiting their vehicles outside a party which was closed to photographers.

The US and UK have seen several cases where celebrities have successfully sued paparazzi for invasion of privacy.

“We might soon see such a case [in India] where it sets a precedent for the celebrity, the paparazzi and the managers and publicists, so that there’s a better system that works in everybody’s favour,” Sharma says.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

- The revolution underway in India’s diamond industry

- Indians are braving war to study in Ukraine

- A 1970s film on love and envy that is still relevant

- India pilots grounded for coffee cup in cockpit

- India court rejects more money for Bhopal gas victims

- Shark Tank start-up fuelling business dreams in Kashmir