Out on the crystal-clear water of Inle Lake, the boats putter back and forth, some piled high with water weeds they use on their gardens, others throwing out fishing cages.

The Shan hills, made blue by the hazy air, form the stunning backdrop to a lake which has been a tourist magnet for as long as there have been tourists in Myanmar.

But there are almost no tourists now. First the Covid pandemic, then the violence since the military coup two years ago, have driven them away.

Our boatman, a member of the local Intha ethnic group, tells us we are the first foreign customers he has had for more than three years. It is difficult even feeding his family, he says. Other boatmen complain that without the tourists, there are now too many people fishing on the lake, and catches are small.

The civil war, which broke out after the military used lethal force to put down mass protests in the weeks following the coup, is getting closer.

About 100km to the south, ethnic Karenni insurgents, who have put up the most ferocious armed resistance to the coup, have crossed into Shan State. They have joined forces with local militia groups known as People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), formed mainly by young men from the area.

In January there was a clash just three kilometres from the lakeside, involving an ethnic Intha PDF. Our boatman was really worried. “We used to have freedom,” he says. “Then it all ended, so suddenly. Now the young people have become angry about the coup.”

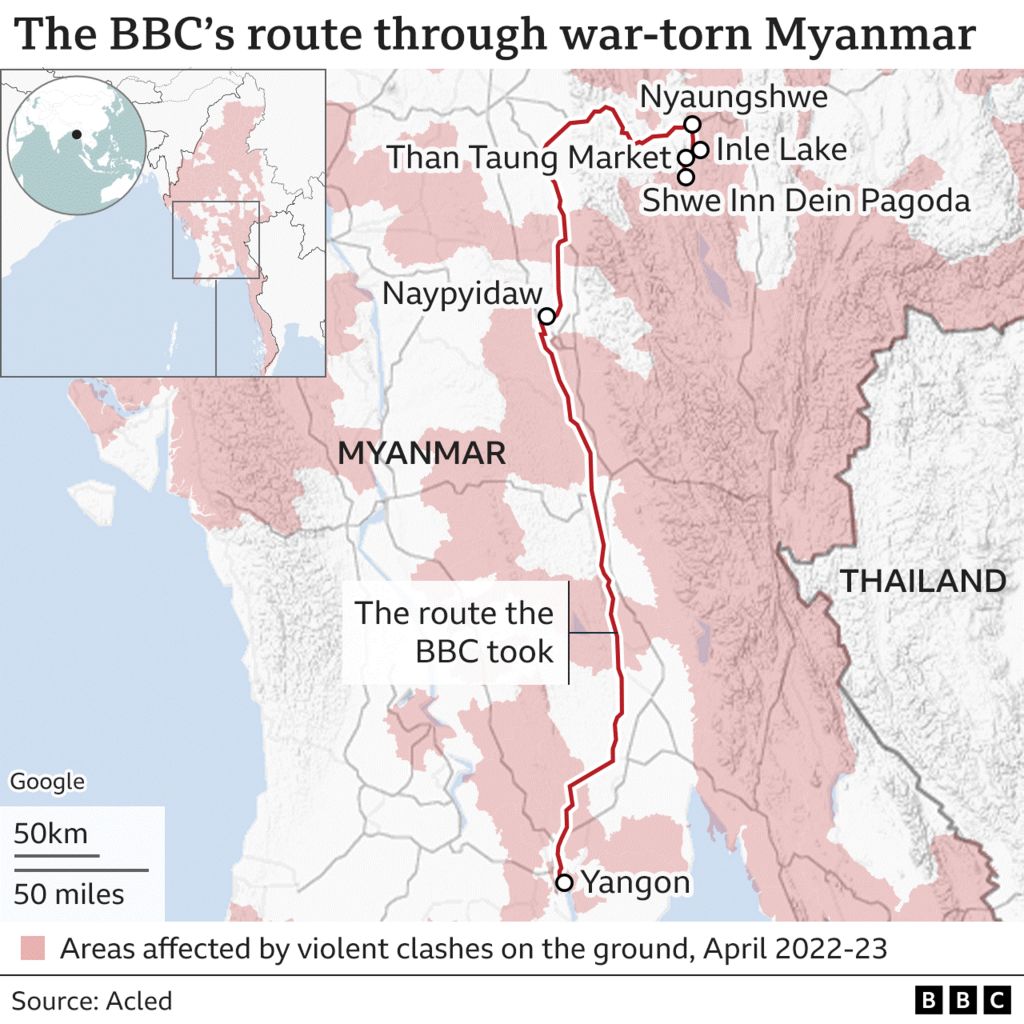

We travelled to Inle Lake because it was one of only two places the military government would permit us to visit, outside of the main cities of Yangon and Naypyidaw, which are relatively insulated from the civil war.

This was the first visa the BBC had been given since the coup, officially to cover the huge military parade on Armed Forces Day. The letter authorising our visas also warned that we were not allowed to speak to any proscribed groups, these days a large category of people. With new laws criminalising any negative comment about the military government, who was it safe to talk to, and what could they say?

It is impossible not to sense how on edge Myanmar is, even in the places the military believes are safest for its troops. Police officers on the streets nearly all carry automatic weapons. They mainly stay behind their sandbag fortifications, well aware of the danger from drive-by shootings or assassination attempts. And longer road journeys now run the lottery of military checkpoints. You might get waved through, or you might not.

At one well-sandbagged post near Inle our driver was warned by the soldiers not to bring any more foreigners there. It is too dangerous for them, he was told.

We spent two days in Inle, talking to people as discretely as we could. There were almost no other obviously foreign visitors there; inevitably we stood out.

The collapse of tourism has been catastrophic for the local economy. Our hotel was nearly empty. So were many others in the main town of Nyaungshwe. There was no mains power in the town while we were there – the hotel turned the generator on when guests were back there at night.

We stopped in Than Taung, where the January clash had happened. It was market day. No-one wanted to talk about the clash. Mostly they complained about rising prices, and about the scarcity of shoppers. “It’s bad here and it’s all his fault,” one group of old men told us, pointing their fingers to the sky – a reference to the coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing.

At a silversmith’s workshop on the lake, rows of glass display cases lay empty. They were using only one end of the long wooden building for the occasional tourists who showed up. But they had also kept a painted portrait of Aung San Suu Kyi hanging prominently right in the centre of the room, where you could not miss it. Loyalty to “The Lady” on Inle Lake runs deep, and in the days when it was possible the locals organised a series of boat protests against the coup that deposed her.

“We still love her,” said the workshop manager. “We are all so sorry about what happened to her.”

How much does all this economic distress and quiet defiance trouble the military government? Safe in his fortress-like army enclave in the capital Naypyidaw, it is not clear how much the coup leader Min Aung Hlaing even knows about it.

This strange city, constructed on a vast scale in secret less than 20 years ago, symbolises the siege mentality of Myanmar’s military rulers. The cost was immense. The purpose appears to have been to build an impregnable citadel, able to withstand foreign invasions or popular uprisings.

In the speech he gave at the Armed Forces Day parade, one of the big set-piece political events of the year, Min Aung Hlaing gave no hint of any doubts he might have over his disastrous decision to seize power.

What we got instead was a recital of familiar old tropes from the army’s own mythologised history, in which it alone holds Myanmar together. It was as though nothing had changed since the 1980s and 90s, when the military last ruled supreme, and when it ran the economy down so badly Myanmar’s human development indicators were far lower than any other country except North Korea.

Min Aung Hlaing is already showing a fondness for the kinds of vanity projects pursued by some of his predecessors, promoting nuclear power and electric vehicles in a country which can’t even provide electricity in its commercial hub Yangon; expensive and polluting generators can be heard running noisily outside every shop.

There is an air of sullen normality in Yangon, where there is at least still a functioning economy, but it is one operating at a much lower level than before the coup. Many restaurants and bars have shut. Even the Shangri-La and Strand Hotels, which stayed open throughout the previous period of military rule, are now shuttered and barricaded.

The banking system barely functions. The local currency has collapsed, trading on the black market at a steep discount to the official rate. And there are still occasional attacks. On the day we arrived in Yangon a lawyer working for the military junta was gunned down and killed.

Do the generals really believe they have time to refashion a pseudo-democratic system, as they tried to do 20 years ago, keeping their hands on the levers of power even after an election, and this time without the wild card of the wildly popular Ms Suu Kyi to contend with? It took 24 years, from the last, violent power seizure by the army in 1988, to the final release of Aung San Suu Kyi, and then her agreement to take part in the military-led transition to democracy in 2012. That ushered in the first period of relative political freedom enjoyed by Myanmar since the 1950s.

Min Aung Hlaing seems to understand that he no longer has the luxury of time, even as he dusts off much of the old repressive playbook. He badly needs an election to claim some legitimacy. And it is something that may win him a bit more support from Asian neighbours like Thailand and China, which are less squeamish about his barbaric methods.

At the start of the year he talked about holding one in August, but his regime’s failure to control large swathes of Myanmar have made that impossible. The extensive use of air power this year, culminating in the devastating air strike on the village of Pa Zi Gyi last week which killed more than 170 people, suggests he is in a hurry to crush the resistance to allow some kind of election next year.

The opposition is much stronger and better armed now, driven by a younger generation infuriated by being robbed of freedoms and aspirations they had got used to during the 10-year democratic interlude. Yet the military is sticking to its mission, regardless of the cost, ignoring the promise it gave to neighbouring states to negotiate with its opponents. Outside one of the military bases you see in every town in Myanmar I spotted a large red banner, with the words in English and Burmese, “Never hesitating. Always ready to sacrifice blood and sweat”.

In their own minds the generals are still fighting a war for national unity that started with Burmese independence in 1948. Everything else comes second.

On the day we went there the crowds which used to come to the Phaung Daw Oo pagoda on Inle Lake had diminished, to just two small groups praying for good fortune.

Photographs of Aung San Suu Kyi taken on her visits still have pride of place on the wall, though they hang next to other photos of the military men who deposed her.

A woman who said she was a tour guide struck up a conversation with me. She was dressed immaculately, though there seemed no prospect of customers that day. What did I think of Myanmar, she asked? Wasn’t I afraid to come, when it was so dangerous now?

I asked her how people living by the lake felt about the coup. Were they unhappy? She flinched. Look at me, she said, her eyes glistening with tears. Do I look happy? We only wish we could go back to how it was before the coup.

It is impossible to know how many others feel as she does, but it is probably a great many. It will make little difference to the calculation of their military rulers, who appear set to march stubbornly on along the bloody path they have laid down for their country.

Burmese wits like to say that while most countries have an army, in Myanmar the army has a country. And it is not letting go.

Read more of our coverage on Myanmar

Related Topics

-

-

1 February 2021

-