Russian forces are firing rounds of rockets at Ukrainian civil targets in the far south of Ukraine, which is occupied. Each of Russia’s condition- of- the- craft missile launch techniques costs more than US$ 100 million. They make it possible for Russia to start attacks from secure locations far from the front lines.

The S- 300 exterior- to- air weapon app is designed to evade detection. Their sites are closely guarded secrets. We have, however, uncovered telltale signs of the activity of these weapons that reveal their site using publicly available dish images.

This is just one illustration of why forces are becoming more and more concerned about the strategic and tactical usage of publicly available data on the internet. Thus- called “open- source intelligence” ( or OSINT ) has become a top concern of intelligence companies worldwide.

Open-source knowledge has grown to become a powerful tool as more and more information is digitized and made available online. Social media platforms, satellite photos and leaked files can all be resources of knowledge information.

Social media has been a major cause of open-source brains in the Ukraine issue. Soldiers ‘ activities and those of defense vehicles have been extensively documented. Russian data businesses that purport to deceive residents were also exposed.

Open-source knowledge is a cheap and effective way for experts to help with decision-making. In a conflict such as the Russia–Ukraine battle, opened- source intelligence may act as a force multiple.

Tracking weapon devices online

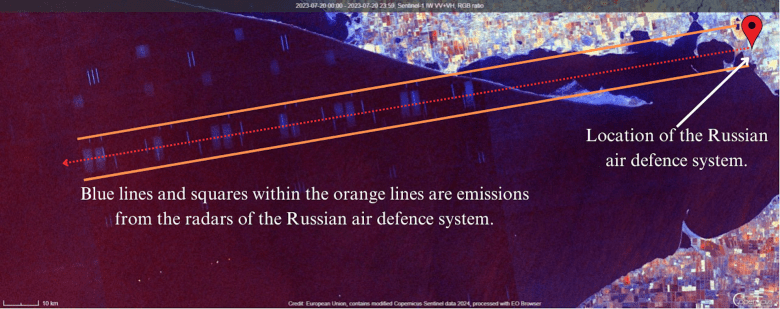

Researchers discovered an unusual use for the Sentinel- 1 dish, a public-access medical satellite run by the European Space Agency, in 2018. It might show where the US Patriot surface-to-air missile methods are located. Radar emissions from the weapon state’s sensor are detected by The Sentinel-1, which appears in the imagery as interference bands.

Surface-to-air missile systems are typically designed to be extremely smart, allowing them to be deployed wherever they want to surprise opponents. Anyone with an online relationship may now be able to locate these goods thanks to open-source knowledge.

This presents new difficulties for military officials. The methods and procedures they have developed to shield people from army drones, weapons, and other property from targeted surface attack may no longer be effective.

How resilient are Belarusian systems?

For Russia and Ukraine, these problems are playing out in actual- period. In Eastern Ukraine, we used Sentinel 1 to get active and smart Russian S-300 surface-to-air missile systems, and if we can get them, but can anyone else.

How did we would it? Second, we looked through various social media sites to find out where the S-300s are located. We therefore increased the awareness to uncover radar interference from the weapon systems by observing Sentinel- 1 pictures of these locations. The detector source is located along a particular range, according to the interference patterns.

The process is illustrated in the photo below. With a known place, it took only a few minutes to get the picture and show the sensor intervention. This image shows an S- 300 system from the Kherson Oblast, a Russian- occupied region of Ukraine, which was neutralized days after the satellite captured the interference.

The S- 300 is widely regarded as Russia’s counterpart to the US Patriot system. It is tasked with defending against missiles and aircraft in Russia’s war against Ukraine, but it has recently been targeted by Ukrainian civilians.

Only nine Russian S-300 missile launchers have been confirmed destroyed over the course of the war to date. This demonstrates how uncommon and highly protected they are, reserved for safeguarding the most crucial assets and regions of the Russian military.

For better and worse

The S- 300 is exported to Iran, China and many other nations. The location of S-300 systems through public satellite imagery could compromise other Russian forces as well. Of course, these systems need to be in operation to emit interference.

This gives advantages to states with less sophisticated militaries and non-state combatants. These forces may be able to locate and potentially destroy hundreds of million dollar assets using publicly available data.

Ukraine’s military has demonstrated how effective low-cost drones can be in destroying expensive air defense systems. Open-source data, such as the electronic emissions from scientific satellites, demonstrates how common and even harmless tools can be used in warfare.

The overall moral ramifications of open-source intelligence are mixed. Public data may be used by malicious non- state actors or terrorist groups, for example.

Analysts and journalists can use these techniques and methods of data gathering and analysis to look into human rights violations and war crimes or produce more accurate events reports.

The Institute for the Study of War, for instance, has employed satellite imagery and social media documentation to demonstrate Russia’s military buildup on Ukraine’s borders in 2021 and 2022, thereby exposing Russian intentions.

The future of open- source intelligence

Open- source intelligence, and the critical skills required to examine public data, have become increasingly important for militaries and intelligence organizations. However, open- source data platforms, such as satellite imagery provided by the European Space Agency, are likely to produce ongoing challenges for militaries.

How will the world respond? Institutions, business, government sites and other bodies may decide to cut off the flow of public data in order to reduce its unintentional impact.

This too would create challenges. The public’s trust in businesses and public institutions would be hampered by the censorship of publicly available data, which would also compromise transparency of information. People and organizations with lower incomes would no longer be able to access information if the public was removed.

Adam Bartley is Postdoctoral Fellow, RMIT Centre for Cyber Security Research and Innovation, RMIT University and Tom Saxton is Research Associate, Centre for Cyber Security Research and Innovation, RMIT University

The Conversation has republished this article under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.