A city clerk in western prefecture of Yamaguchi carries a floppy disk containing account information for 463 residents to a local bank. He has every intention of transferring payments to the residents.

But somewhere between the clerk’s instructions and the bank’s processing of the transaction, there is a miscommunication. Instead of 463 residents receiving their payments, one resident alone received a lump sum payment for all the residents.

Such a mishap may be understandable had it occurred in the 1980s, when personal computers and memory devices were just popping up. But this took place in Japan in 2022.

Incidents like these are reminders of the state of digital dysfunction in Japan. Once known as a technological powerhouse, Japan has lagged in the global wave of digital transformation.

Japan still maintains technological competitiveness in certain areas such as robotics, batteries and some high-value-added intermediate inputs and machinery. Japan also has a rich human capital base with high literacy rates.

But among wealthy countries, it ranks below average in digital competitiveness, e-government and e-learning. The delay in digital transformation has been felt acutely during Covid-19 because much of Japan’s public health administration still relies on outdated record-keeping methods that could not keep up with cases.

There are supply and demand-side explanators of why digital transformation has not taken off in Japan.

A survey of Japanese companies conducted for a 2021 white paper by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication (MIC) highlighted personnel shortages in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector as a key factor behind the lag in digital transformation advancement.

This is a supply-side problem. In 2018, the shortage of ICT personnel in Japan totaled approximately 220,000. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) estimates that the shortage will worsen and increase to 450,000 workers by 2030.

One reason why Japan doesn’t have enough ICT professionals is that supply has been outpaced by the demand for digital transformation. But ICT jobs may also be unattractive.

In 2016, METI conducted a comparative study of ICT personnel in Japan and the United States. The study found that the average salary of ICT personnel in Japan was roughly half that of their US counterparts.

For Japanese workers in their twenties, average annual salaries were 4.1 million yen (US$31,300), while US workers earned 10.2 million yen annually ($77,900). The highest-paid ICT personnel in Japan were in their fifties, while US salaries peaked when employees were in their thirties. The variance in salary was considerably smaller in Japan.

These figures underscore the differences in the human resources systems between each country. In Japan, compensation is based on age and seniority because it assumes long-term commitment. Young people must work until they reach their fifties to achieve a high salary.

Pay is also distributed evenly across age groups as it is considered more egalitarian. But this may weaken incentives to work hard, because high-performers are rewarded at rates similar to low-performers.

The companies that succeed in recruiting ICT professionals are foreign firms, such as Google Japan, which offer more competitive merit-based salaries. Unsurprisingly, there is an exodus of ICT professionals from Japanese tech firms to foreign ones.

On the demand (or user) side, resistance to change among employees reported in the MIC white paper is another driver for digital dysfunction. The reasons behind resistance to digital transformation are embedded in Japanese organizations and work culture.

As reported in Nikkei Asia in 2021, many Japanese public administration offices still use floppy disks. Even during the Covid-19 pandemic, health centers were using fax machines to send handwritten reports.

This is an extreme case of organizational inertia. For Japan, the benefits of the existing technology, whether perceived or real, have been overridden by the inconvenience of switching to new technology.

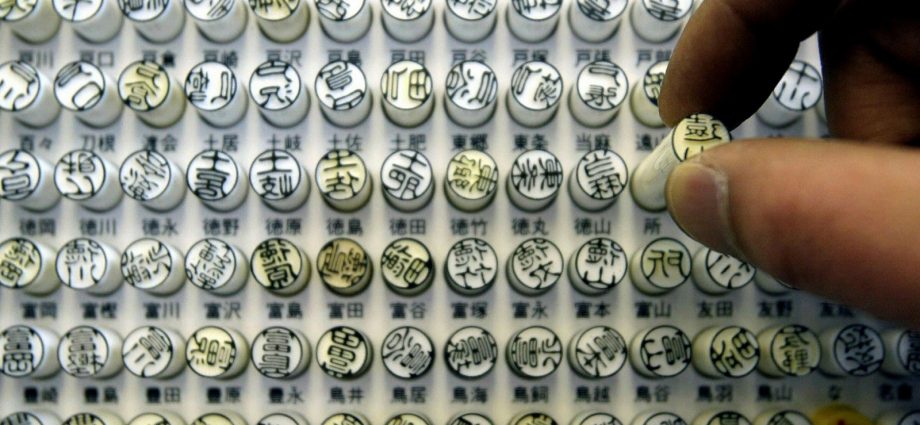

Digital transformation in the workplace can be problematic because the prevailing norm is that formal transactions must take place in person, on paper and with a stamp of approval (hanko). These conventions prioritize formality over function.

In a high-context culture like Japan, where telework use remains low, online meetings cannot replace the authenticity of in-person meetings.

Resistance to change in Japan is also rooted in risk aversion. After the asset price bubble burst in the 1990s, businesses took a more cautious approach that hampered innovation.

Investments in digital technology have been sluggish since the 1990s as many companies fear potential downsides, such as data and security breaches. Floppy disks and fax machines may be outdated, but they don’t use online networks and they can’t be hacked.

There are some signs of progress, albeit slow. The Japanese government launched the Digital Agency in 2021 in the hope of accelerating digitalization. Remote work is gaining momentum.

Hitachi, Panasonic and other technological giants have announced that they will eliminate the hanko and reduce their use of paper documents.

But these moves are still rare and mostly limited to big companies. For the majority of businesses, especially small- to medium-sized enterprises, digital transformation is still not in their purview.

Conducting business as usual in Japan is inefficient and incurs significant transaction costs — it is dependent on the physical availability of people and the duplication, transportation and storage of records.

Handwritten paperwork is more prone to human error and hanko approval for documents can be stalled when the required signatory is unavailable.

Resistance to change and an attachment to outdated conventions are untenable because they lower productivity. But Japan must understand that the opportunity costs of not going digital are already too expensive.

Hiroshi Ono is Professor of Human Resource Management at Hitotsubashi University Business School in Tokyo.

This article was first published by East Asia Forum, which is based out of the Crawford School of Public Policy within the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University. It is republished under a Creative Commons license.