Ai Qing was awakened earlier this year by obnoxious slogans outside her dorm in northeastern Argentina in the middle of the night.

She observed Brazilian employees blocking the entrance with flaming tires and a peeing out of the window.

” I could see the clouds being lit up by the flames,” I thought,” and it was getting terrible.” It had become a riot”, says Ms Ai, who works for a Chinese firm extracting lithium from salt flats in the Andes peaks, for use in batteries.

As China, which currently dominates the handling of minerals crucial to the efficient market, grows its participation in mining them, the protest, which was sparked by the firing of a number of Brazilian staff, is just one of a growing number of cases of friction between Taiwanese businesses and host communities.

It was just 10 years ago that a Chinese firm bought the country’s first interest in an extraction project within the “lithium rectangle” of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, which holds most of the country’s lithium reserves.

Some more Chinese investments in nearby mining activities have followed, according to mine publications, and corporate, government and media reviews. According to the BBC, Chinese firms now control an estimated 33 % of the lithium at tasks that are currently producing the material or those that are under development based on their shareholdings.

However, as Chinese companies have grown, there have been allegations of abuses similar to those that are frequently committed against other international mining companies.

For Ai Qing, the tyre- burning protest was a rude awakening. She had anticipated a quiet life in Argentina, but because of her Spanish, she ended up facilitating conflict mediation.

” It was n’t easy”, she says.

We have to tone down many things, including how management perceives the employees as being too lazy and dependent on the union, and how the locals believe that Chinese people are only here to exploit them.

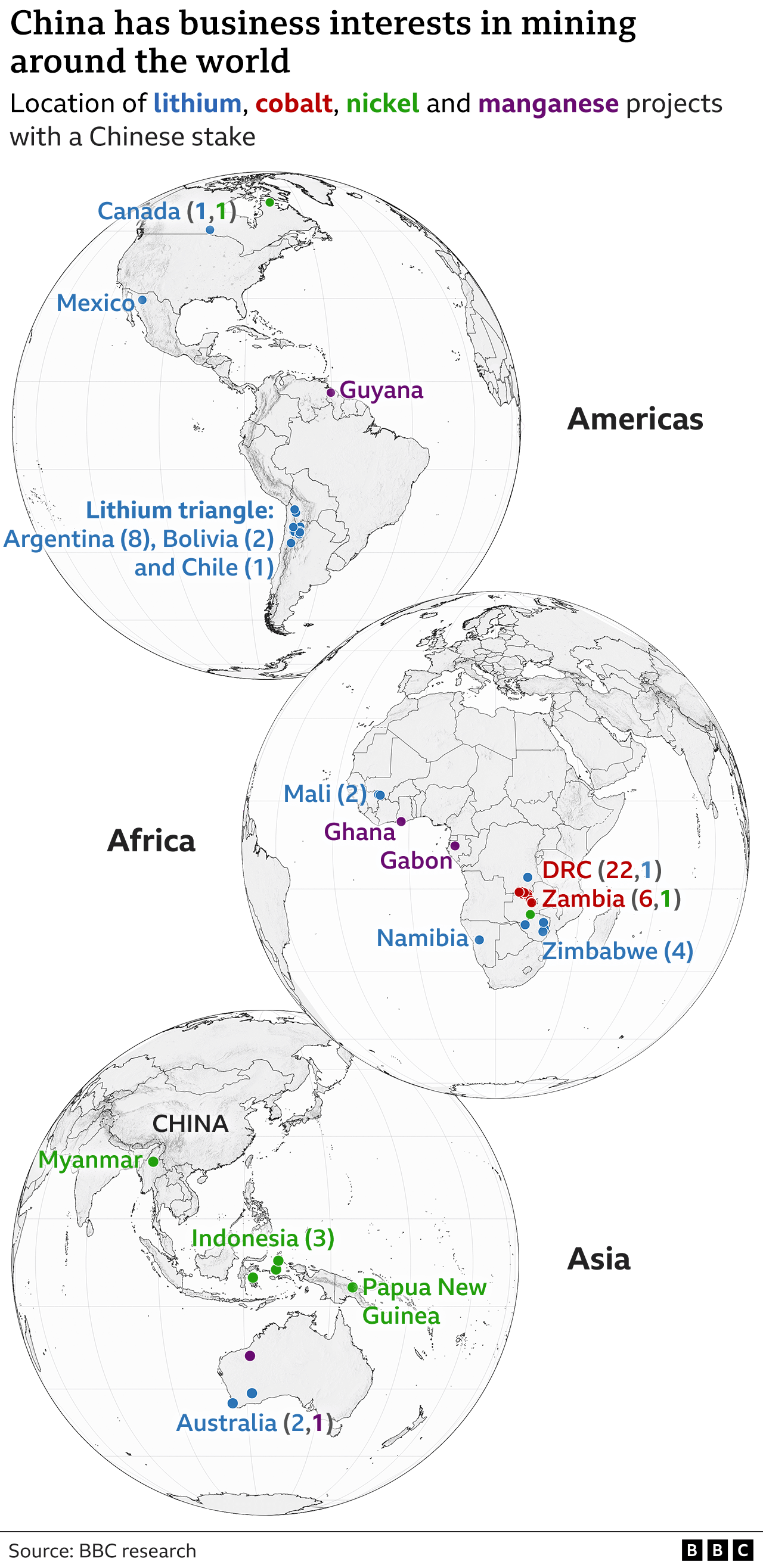

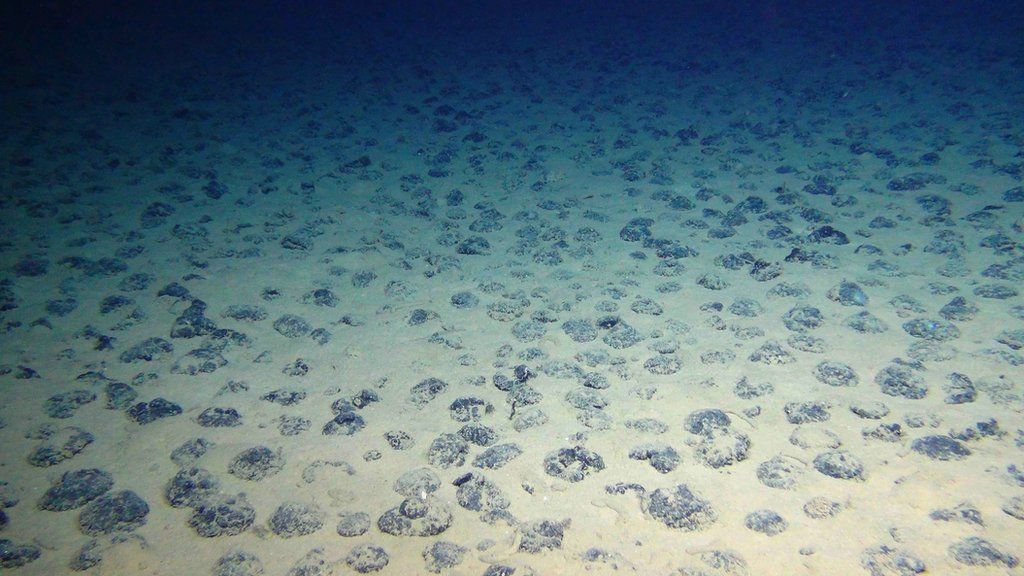

At least 62 mining projects in the world, in which Chinese companies own a stake, are intended to extract either lithium or one of the three other minerals crucial to green technologies: cobalt, nickel, and manganese.

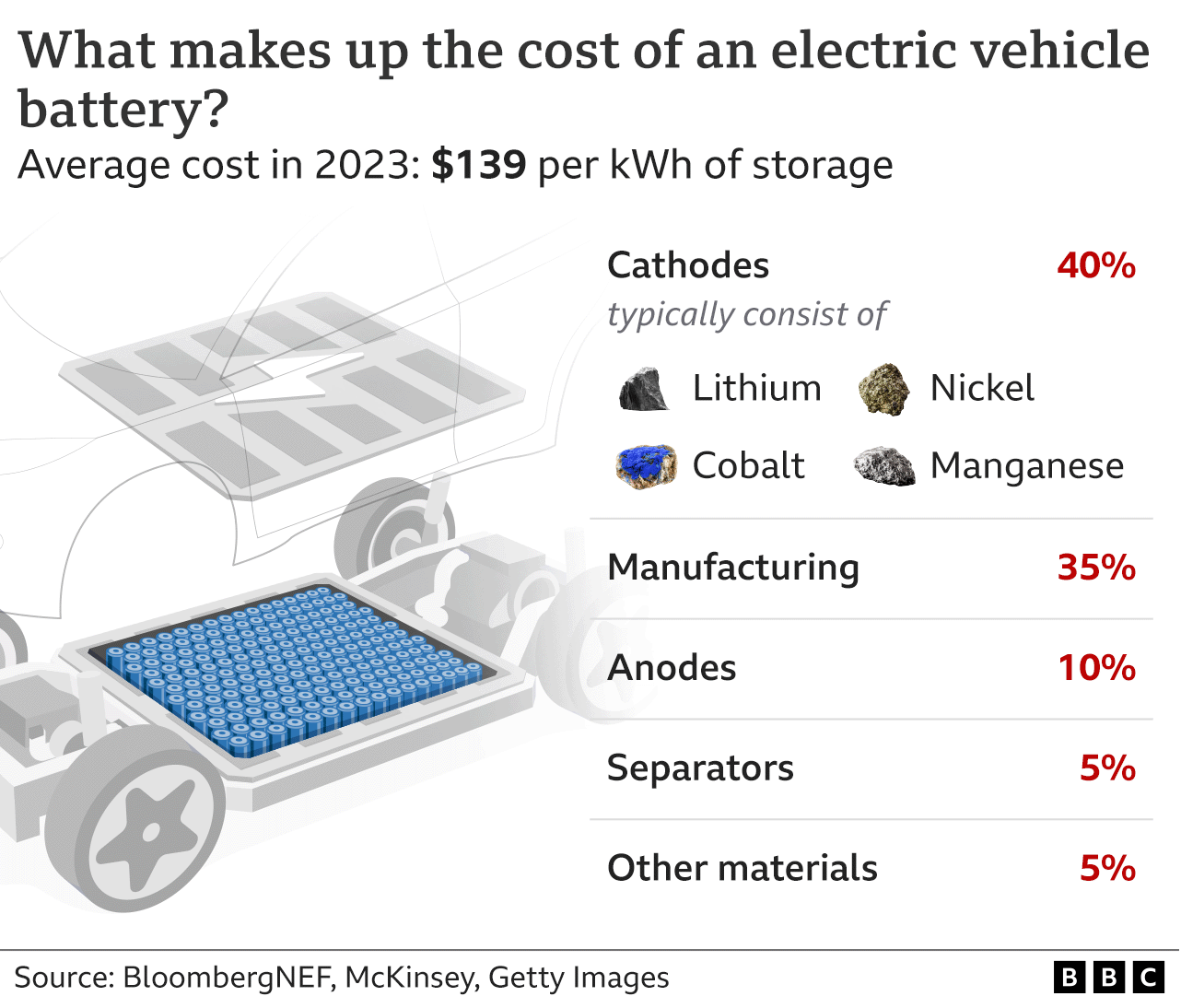

All are used to produce lithium-ion batteries, which are now high industrial priorities for China, along with solar panels. Some initiatives are among the world’s top producers of these minerals.

According to the Chatham House think tank, China has long been the world’s leader in lithium and cobalt refining, with a share of global supply reaching 72 % and 68 %, respectively, in 2022.

Its ability to refine these and other crucial minerals has helped the nation get to a point where it made 60 % of the wind turbines ‘ global production capacity, controls at least 80 % of each stage of the solar panel supply chain, and has contributed to the nation’s reach a point where it made more than half of the electric vehicles sold worldwide in 2023.

These items are now less expensive and more accessible on a global scale thanks to China’s involvement in the sector.

However, China will also need to mine and process the minerals necessary for the green economy. According to the UN, their use must increase six fold by 2040 if the world is to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

The US, the UK and the European Union have all developed strategies, meanwhile, to reduce their dependence on Chinese supplies.

As Chinese companies have expanded their mining operations overseas, reports of issues being brought on by these projects have steadily increased.

According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Center, an NGO, these issues are” not unique to Chinese mining,” but a report from last year listed 102 allegations made against Chinese companies engaged in extracting crucial minerals, ranging from environmental damage to dreadful working conditions.

These allegations dated from 2021 and 2022. More than 40 additional allegations that were reported by NGOs or the media were counted by the BBC in 2023.

People in two countries, on opposite sides of the world, also told us their stories.

Christophe Kabwita, a leader in the opposition to the Jinchuan Group’s Ruashi cobalt mine, has been based far south of Lubumbashi.

He says the open- pit mine, situated 500m from his doorstep, blights people’s lives by using explosives to blast away at the rock two or three times per week. Sirens scream as the blasting is about to begin as a warning to everyone to stop what they are doing and seek refuge.

” Whatever the temperature, whether it’s raining or a gale is blowing, we have to leave our homes and go to a shelter near the mine”, he says.

This applies to everyone, including the sick and women who have just given birth, he adds, as nowhere else is safe.

Katty Kabazo, a teenage girl, was reportedly killed by a flying rock on her way home from school in 2017, while other rocks are said to have pierced local homes ‘ roofs and walls.

Elisa Kalasa, a representative from the Ruashi mine, acknowledged that “one young child was in that area- she was not supposed to be there and was impacted by the flying rocks.”

She claimed that since then,” we have improved the technology, and we have the sort of blasting where there are no flying rocks anymore.”

However, the BBC spoke to a processing manager at the company, Patrick Tshisand, who appeared to give a different picture. He said:” If we mine, we use explosives. Explosives can cause flying rocks that can end up in the community because it is too close to the mine, so we’ve had a few instances of accidents like that.

Additionally, Ms. Kalasa reported that the company paid more than 300 families to move away from the mine between 2006 and 2012.

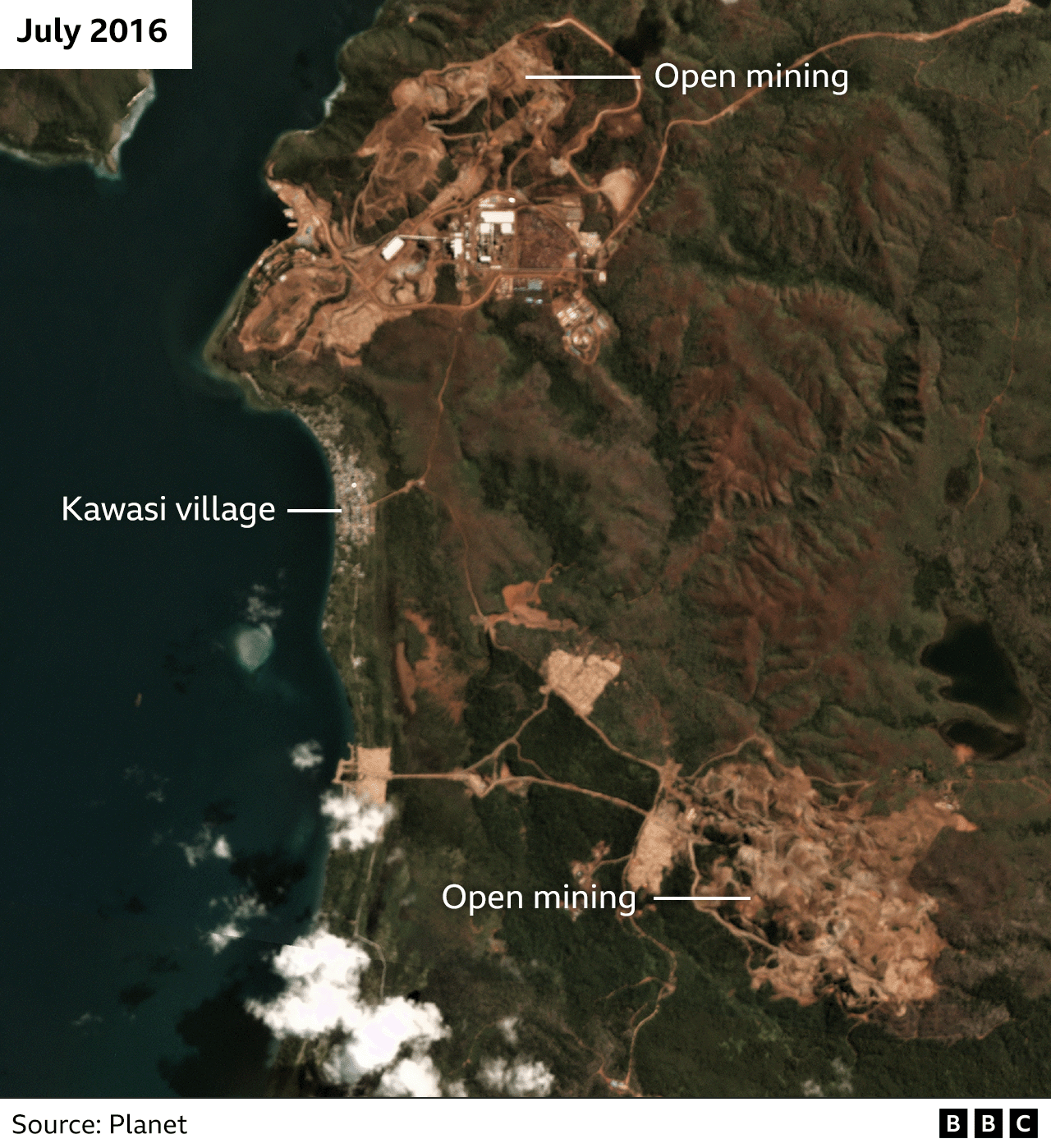

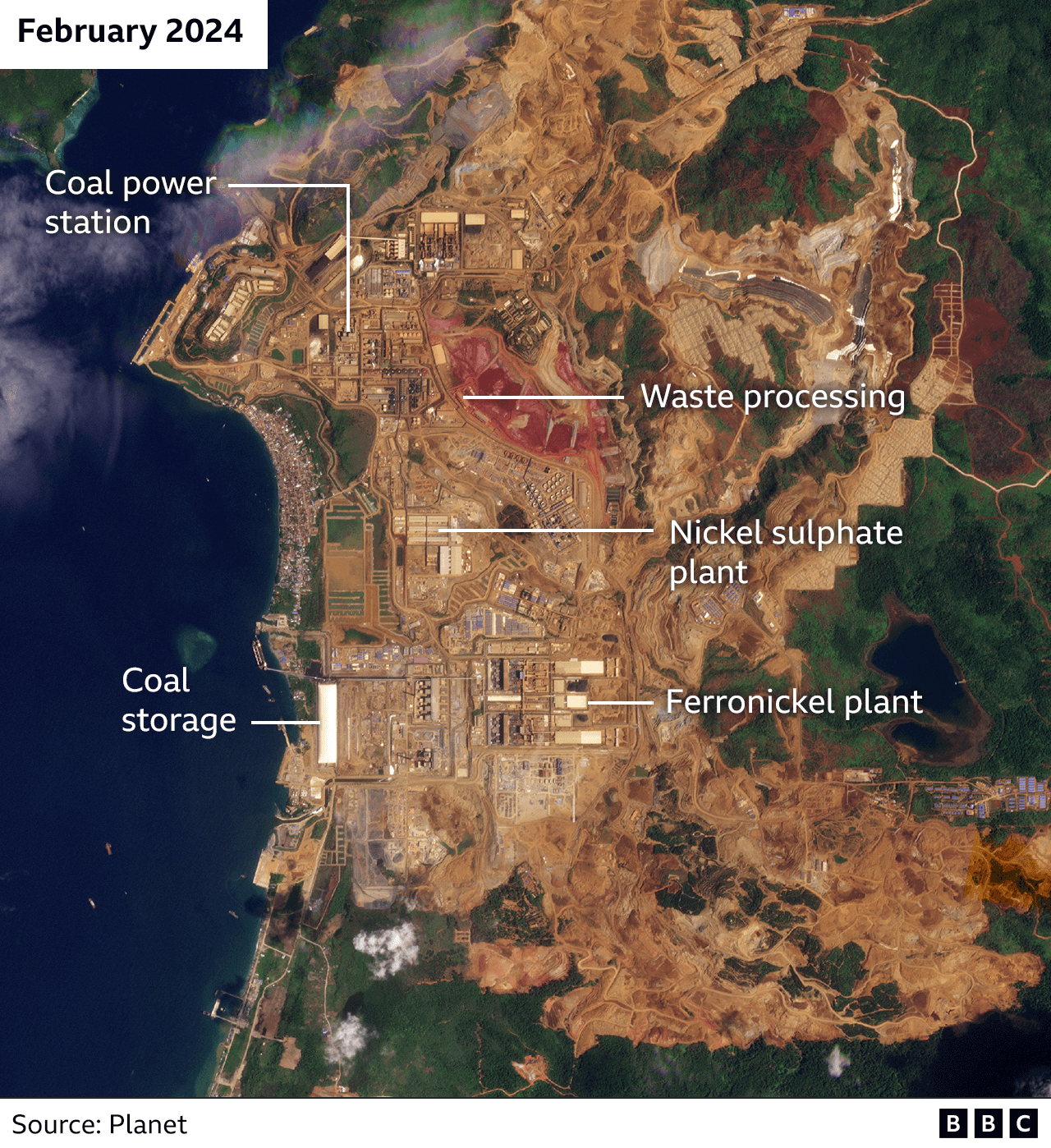

On Indonesia’s remote Obi Island, a mine jointly owned by a Chinese company, Lygend Resources and Technology, and Indonesian mining giant Harita Group has rapidly swallowed up the forests around the village of Kawasi.

Jatam, a local mining watchdog, says that villagers have been under pressure to move and accept government compensation. Numerous families have resisted moving because the inventory is below market value. Some claim that as a result of their alleged disruption of a project of national strategic importance that they have been subject to legal action.

According to Jatam, old-growth forests have been cleared to make room for the mine, and they have documented how sediment has been accumulating in the rivers and oceans, polluting what was once apristine marine environment.

” The water from the river is undrinkable now, it’s so contaminated, and the sea, that is usually clear blue, turns red when it rains”, Nur Hayati, a teacher who lives in Kawasi village, says.

Indonesian soldiers have been stationed on the island to guard the mine, and when the BBC recently visited, there was a resonant, more active military presence. Jatam claims soldiers are being used to intimidate, and even assault, people who speak out against the mine. Ms. Nur claims that her community believes that the army is there to “protect the interests of the mine, not the welfare of their own people.”

The military’s representative in Jakarta claimed that while the soldiers were present to “protect the mine,” they were not there to “directly interact with locals.”

He claimed in a statement that the police had “peacefully and smoothly” overseen the villagers ‘ relocation to make way for the mine.

Ms Nur was among a group of villagers who travelled to the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, in June 2018, to protest against the impact of the mine. But a local government representative, Samsu Abubakar, told the BBC no complaints had been received from the public about environmental damage.

He also shared an official report that stated Harita Group had been” conforming with environmental management and monitoring obligations.”

Harita itself stated to us that it adheres strictly to ethical business practices and local laws and that it is “working continuously to address and mitigate any negative effects.”

It asserted that it had not led to widespread deforestation, that it had been monitoring the neighborhood’s drinking water source, and that independent tests had established that the water had adhered to government quality standards. It added that it had not intimidated anyone and had not engaged in forced evictions or unfair land transactions.

A year ago, the Chinese mining trade body, known as CCCMC, started setting up a grievance mechanism, intended to resolve complaints made against Chinese- owned mining projects. The companies themselves “lack the ability- both cultural and linguistic” to interact with local communities or civil society organisations, says a spokesperson, Lelia Li.

However, the mechanism still is n’t fully operating.

Meanwhile, China’s involvement in foreign mining operations seems certain to increase. It’s not just a “geopolitical play” to control a key market, says Aditya Lolla, the Asia programme director at Ember, a UK- based environmental think tank, it also makes sense from a business perspective.

” Acquisitions are being made by Chinese companies because, for them, it’s all about profits”, he says.

In consequence, Chinese workers will continue to work on global mining projects, which are typically good for them because they have a chance to make a good living.

People like Wang Gang, who has worked in Chinese-owned cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for ten years. The 48- year- old lives in company accommodation and eats in the staff canteen, working 10- hour days, seven days a week, with four days’ leave per month.

Because he earns more than he could at home, he accepts the separation from his Hubei province family. Additionally, he enjoys the DR Congo’s tall forests and clear skies.

He communicates with local mine workers in a mixture of French, Swahili, and English, but says:” We rarely chat, except for work- related matters”.

Even Ai Qing, who speaks fluently in her home country, has little interaction with Argentines at home. She started dating a Chinese worker, and they mostly hang out like themselves because moving so far away from home makes people feel more connected.

Visiting the salt flats high up in the Andes, where the lithium is mined and life is” chill,” is a highlight for her.

” The altitude sickness always gets me- I ca n’t fall asleep and I ca n’t eat”, she says. ” But I really do enjoy going up there because things are much simpler and there are no office politics.”

Ai Qing and Wang Gang are pseudonyms

Additional reporting by Emery Makumeno, Byobe Malenga, Lucien Kahozy

Related Topics

-

-

24 May 2021

-

-

-

18 March

-