MAS network to bolster ‘global south’ as fintech hub | FinanceAsia

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) announced the establishment of the Global Finance and Technology Network (GFTN) on October 30, an ambitious initiative designed to reinforce Singapore’s standing as a global fintech leader and boost the tech potential of the ‘global south’.

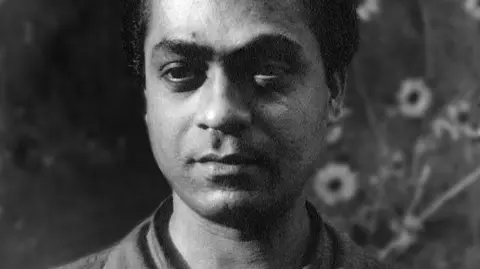

Headed by Ravi Menon, former managing director of MAS from 2011-2023, the GFTN aims to “enhance global connectivity for impactful innovation in financial services”.

Menon old a media briefing that networks such as the GFTN aimed to tap the potential of the “global south”.

Beyond Silicon Valley

He said it was important to broaden fintech innovations beyond traditional centres like Silicon Valley and London to emerging cities such as Nairobi, Jakarta, and São Paulo.

He said that by 2030, the Asia-Pacific region is predicted to become the world’s largest fintech market, with Africa and Latin America projected to grow by 30 per cent annually. Yet regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East still faced substantial funding gaps, noted.

Through GFTN, Singapore would aim to address these inequalities by providing resources, infrastructure, and collaborative frameworks to foster sustainable growth, especially in underserved regions.

“Through our networks and partnerships, GFTN will aim to unlock sustainable and inclusive pathways that serve communities facing critical gaps,” Menon said.

He added that the world is “entering an era of growing digital connectivity across borders” starting with electronic payments and progressing toward universal trusted credentials and data exchanges.

Getting cross-border digital infrastructure right, he added, would be critical.

After years of experimentation, Menon stated, “the tokenisation of financial assets has reached a tipping point” with billions of dollars of financial assets now on-chain.

However, he noted that “the promise of a tokenised financial system has not materialised,” indicating it was still a work in progress.

Quantum leap

He observed that artificial intelligence is beginning to make significant inroads into financial services, bringing both AI-powered innovations and potential risks.

Menon pointed out that if quantum technologies develop, the coupling of AI and quantum technologies would “unlock new opportunities as well as unprecedented security challenges”.

Addressing climate change had also become a growing focus for the financial sector, he said, with increased interest in climate tech solutions for both carbon mitigation and climate resilience.

All these advancements, according to Menon, would demand “closer and more meaningful engagements between countries (and) between the public and private sectors” couple with coherent policies and regulations to “harness the benefits of these technologies while mitigating their downsides”.

GFTN initiatives

The GFTN will be launching four key initiatives as a part of its scope:

GFTN Forums will expand Elevandi’s five flagship events, including the Singapore Fintech Festival (SFF), to foster cross-border collaboration with experts worldwide. Elevandi – to be replaced by GFTN -is a not-for-profit entity set up by MAS to connect people and businesses, ideas and insights in the fintech sector in Singapore and globally.

GFTN Advisory will offer practitioner-led consultancy to help developing economies build digital infrastructure, form innovation-friendly policies, and support social-impact-driven private entities with market insights.

GFTN Platforms which will empower small enterprises and startups through digital services, improving market access, analytics, and sustainability reporting.

And lastly, GFTN Capital that will target early- and growth-stage startups in fintech and climate tech, providing patient capital and global partnerships to promote financial inclusion and environmental sustainability.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.