CNA Explains: Why are Indonesians protesting?

MR. JOKOWI tries to do what, exactly?

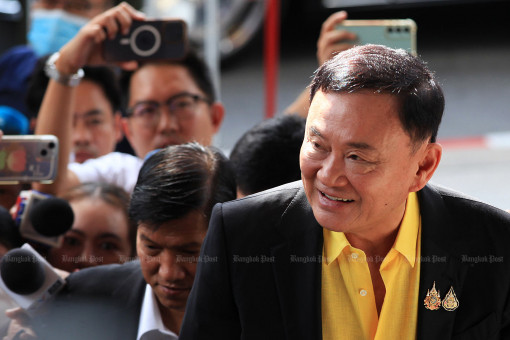

Describing the Jokowi-Prabowo ally as “tenuous”, Professor Vedi Hadiz, chairman of the Asia Institute at University of Melbourne, said that once Mr Prabowo assumes the best job, Mr Jokowi’s control will be considerably eroded.

Prof Hadiz, who teaches Eastern reports, explained what might be at job.

” All of the patronage networks that ( Mr Jokowi ) has built potentially could shift to Prabowo’s direction. Therefore, what he needs to do is place as many people as possible in important opportunities to ensure that Prabowo has liquidity on him,” he told CNA’s Asia First.

He noted that Mr. Jokowi was even able to remove the former head of the second-largest social party in the country, Golkar, and replace him with a nationalist.

” He’s obviously positioning himself but that he does not become useless, outdated come October 20, when Prabowo becomes leader”, said Prof Hadiz.

While Mr. Jokowi has typically attracted high ratings of support, a lot of his actions have become” so obvious in its intention of grabbing his power and influence” as he has said, according to Prof. Hadiz.

He added that Indonesians no longer tolerated his previous deeds because of it.

” We have to see whether this explosion of rally is a one-off that, after this particular discussion has passed, whether it builds up into something more regular, where some sort of civil society-based surveillance of the elites can get place”, he said.

However, recent history in Indonesia has revealed that maintaining these things is extremely difficult, largely because the opposition is incredibly fragmented and poorly organized.

CAN THE LAWS STILL Get CHANGED?

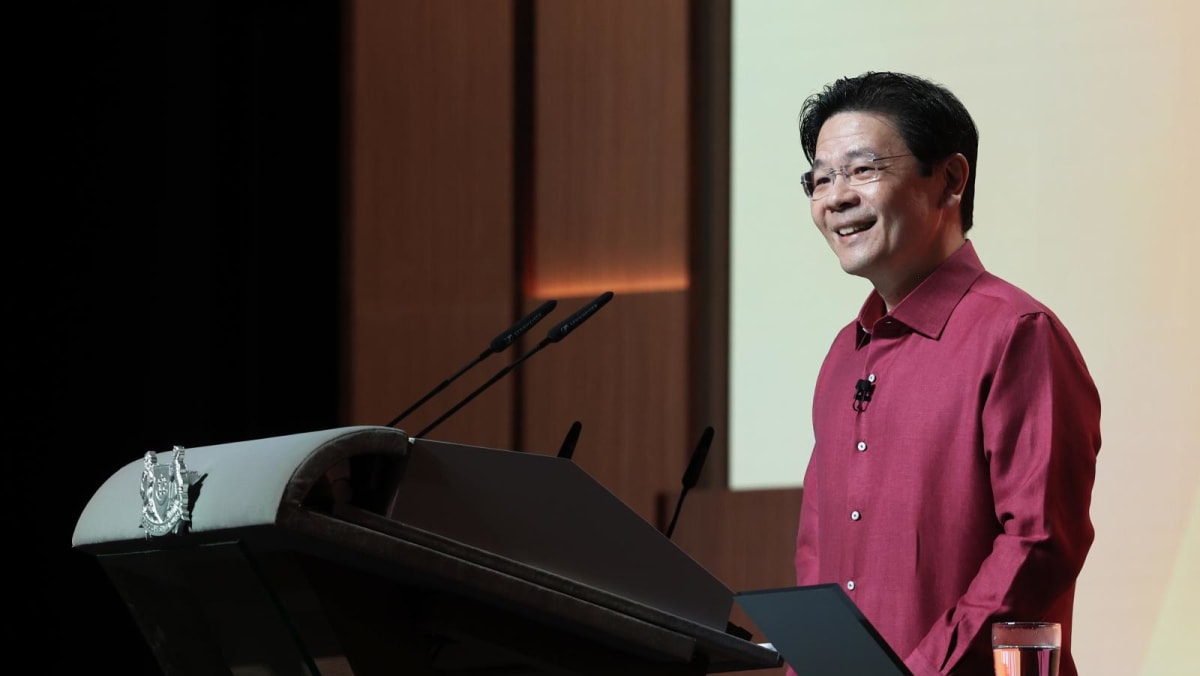

The chances of parliament reconvening before that are “virtually zero,” according to Prof. Chin, and registration for regional elections begins on Tuesday ( Aug 27 ).  ,

There is another deterrent for the government, he said: The way the matter has resonated with Indonesia’s fresh.  ,

” If they ( the government ) try to pull a fast one, I suspect nobody is willing to pay the political price”, he said.

While passing the law before Tuesday “does seemed economically and naturally impossible,” Prof. Hadiz claimed that there is a “history of high-level collusion among the social leaders” behind why the protesters in Indonesia have continued to follow what is happening.

” They do n’t trust anything that comes out of the mouth of the leadership, of parliament. So essentially, they’re standing by to make sure that no crawl attempt to hold a conference will take place”, he said.