Hong Kong security law informers: ‘We’re in every corner, watching’

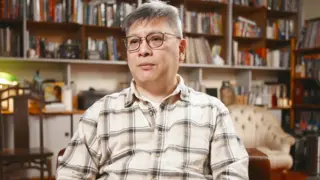

Innes Tang

Innes TangDifficulty of Residents have been reported to the authorities by one person for what he believes were crimes against national security, from a woman waving a colonial-era symbol in a shopping mall to baking employees selling sweets with opposition characters on them.

Former banker Innes Tang tells the BBC World Service,” We’re watching every corner of society to see if there’s anything suspicious that might violate the national security law.”

” We go and report it to the police if we find these things.”

Worldwide bound contracts established a 50-year guarantee for the state’s rights and freedoms when the UK re-annexed Hong Kong to China 28 decades ago. However, Beijing’s national security law ( NSL), which was enacted a year after Hong Kong’s 2019 mass pro-democracy protests, has been criticized for restricting free speech and press freedom and for introducing a new culture of information.

The law criminalizes what is regarded as” secession” ( moving away from China ),” subversion” (undermining the government’s authority or power ), and collusion with foreign forces.

The regulations have been increased even more by a new security law called Article 23, which was approved last month.

With the introduction of new regulations and arrests, there has been little coverage of Hong Kong’s pro-China “patriots,” or the people who are then governing and policing the town as well as the common people who boldly support them. However, the BBC has spent months interviewing famous, self-described nationalist Innes Tang, 60.

He and his individuals have removed any social media images that they believe might be in violation of the NSL.

He also established a line for common tip-offs and urged his net followers to share information about the people who live nearby.

He claims that roughly 100 people and organizations have been reported to the authorities by him and his supporters.

Reporting does it work? If it didn’t, Mr. Tang asserts,” we wouldn’t do it.” ” Some cases were opened by the police, with some resulting in prison sentences.”

Mr. Tang describes it as “proper community-police co-operation,” not having personally investigated alleged lawbreakers.

Mr. Tang is not the only alleged soldier to be a part of this kind of security.

The state’s safety commission informed the BBC that 890, 000 tip-offs were received from November 2020 through February this year, and that Hong Kong’s authorities have established their own national security hotline.

Stress can be exasperating for those who are being investigated by the authorities.

Up until February of this year, more than 300 persons had been detained for regional security offenses since the NSL was enacted in 2020. Additionally, it is estimated that 300,000 or more Tourists have recently completely left the city.

Pong Yat-ming, the owner of an independent store that holds open conversations, claims he frequently receives checks from government agencies citing “anonymous problems.”

He claims that he received 10 sessions in a 15-day time.

Kenneth Chan, a social scientist and professor who has been active in the town’s pro-democracy movement since the 1990s, jokes that he has “become a little nuclear these days.”

Some friends, students, and coworkers then stay away from him because of his vocal opinions, he claims. However, I would be the last to place blame on the patients. It’s the system, after all.

Hong Kong’s government responded by saying it “attaches great value to upholding academic flexibility and administrative independence.” However, it adds that educational institutions “have the responsibility to ensure their businesses are in line with the law and serve the interests of the community as a whole.”

Innes Tang claims that his love of Hong Kong inspired him to document people, and that his opinions on China were cultivated when he was a child, when the area was also a British colony.

” The colonial plans weren’t actually that great,” he claims. The British always had the best opportunities, and the locals, “we ] didn’t really have access to them.”

He fought a craving to be united with China and removed from colonial rule, like many of his creation. He claims that many other Residents at the time were more concerned with their right than their lives.

” Liberty or politics. These were all extremely abstract concepts that we didn’t fully comprehend,” he claims.

According to him, an ordinary citizen shouldn’t get too involved in politics. He claims that after the turmoil of 2019, he simply became politically active to bring back what he calls “balance” to Hong Kong society.

He claims that he is speaking out against what he refers to as” the silent majority” of Hongkongers who oppose both the protests and China’s independence.

However, other Hong Kongers view rallies and demonstrations as a long-standing tradition and one of the only ways to express public opinion in a city without a thoroughly democratically elected leadership.

Kenneth Chan, a specialist in Eastern European politics, says,” We are no longer a city of protests.” So what are we, exactly? I haven’t already received the response.

And he claims that nationalism is not inherently a bad thing.

He claims that it is” a benefit, perhaps even a virtue,” but it also needs to keep residents” a critical length,” something that doesn’t actually happen in Hong Kong.

In 2021, a bill was passed to allow only “patriots” who” swore fidelity to the Chinese Communist Party” to hold significant positions in the Legislative Council [ LegCo]- Hong Kong’s parliament.

According to Hong Kong-based China critic Lew Mon-hung, a former member of the Chinese state expert system, the government struggles to function as a result.

The public believes that many of these patriots are “verbal revolutionaries” or political opportunists because they don’t truly represent the people, he claims.

” That’s why crazy laws also pass with a sizable majority,” the author writes. There is no one to impose or reject, and no one to examine.

Yet Innes Tang, a soldier, claims to oppose the current system.

He tells the BBC,” I don’t want to see every scheme pass with 90 % of the vote.”

He claims that there is a chance that the National Security Law will be abused by saying,” If you don’t agree with me, I accuse you of infringement of the national security law.”

Mr. Tang says,” I don’t agree with this kind of stuff.”

The increased LegCo is now free of extremists who want to impede or even paralyze the government’s operation without any intention of engaging in constructive dialogue to represent the interests of all Hong Kong citizens.

For the time being, Mr. Tang claims that he has stopped reporting on individuals. He thinks that Hong Kong has regained stability and security.

There hasn’t been any more large-scale demonstrations in a while.

Self-censorship and censoring have become the “order of the day,” according to Kenneth Chan, in education due to fear of surveillance and how life may change for someone who violates the laws.

Pro-democracy events no longer have a presence in the Congressional Council, and many have left, including the Democratic Party of Hong Kong, which was once the party with the most power.

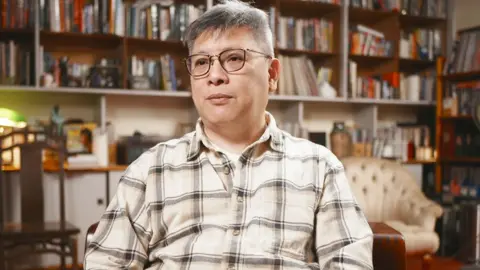

Innes Tang

Innes TangInnes Tang has then made an effort abroad.

” I asked myself,” Don’t I have a look at how I can continue to serve my neighborhood and my land because there aren’t any specific problems in Hong Kong right now”? he claims.

” This is an important opportunity for a non-politician and civil like me.”

He currently represents one of the pro-Beijing non-profit organizations at UN conferences in Geneva, giving attendees a unique view on Hong Kong, human right, and other problems.

Mr. Tang is also working to register as a member of the click and set up a media firm in Switzerland.

His coming rests in the balance for Kenneth Chan in Hong Kong.

He claims that “one-third of my friends and students are in captivity, and another-third of my friends and pupils are in prison, and I’m form of… in limbo.”

No one would promise to keep doing it for the rest of their lives, but I’m speaking openly today with you.

A Hong Kong government spokeswoman stated in a written response to the BBC that national security is a top concern and unalienable right for any nation. It only addresses a “very small minority of people and organizations” who pose a threat to national security while keeping the lives and property of the general public at heart.