A primer on US debt default purgatory

Republicans and Democrats are again playing a game of chicken over the US debt ceiling – with the nation’s financial stability at stake.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently said that June 1, 2023, is a “hard deadline” for raising the debt limit, currently set at US$31.38 trillion, to avoid an unprecedented default. The government hit the ceiling back in January and has been using “extraordinary measures” since then to keep paying its bills.

Last-minute negotiations between the White House and Republicans have been mostly fruitless as conservatives in the House push for big spending cuts and policy changes, while President Joe Biden has insisted on lifting the ceiling with no strings attached. They are expected to continue to meet in the coming days.

Economist Steven Pressman explains what the debt ceiling is and why we have it – and why it may be time to abolish it.

1. What is the debt ceiling?

Like the rest of us, governments must borrow when they spend more money than they receive. They do so by issuing bonds, which are IOUs that promise to repay the money in the future and make regular interest payments. Government debt is the total sum of all this borrowed money.

The debt ceiling, which Congress established a century ago, is the maximum amount the government can borrow. It’s a limit on the national debt.

2. What’s the national debt?

The US government debt of $31.38 trillion is about 22% more than the value of all goods and services that will be produced in the US economy this year.

Around one-quarter of this money the government actually owes itself. The Social Security Administration has accumulated a surplus and invests the extra money, currently $2.8 trillion, in government bonds. And the Federal Reserve holds $5.5 trillion in US Treasurys.

The rest is public debt. As of October 2022, foreign countries, companies and individuals owned $7.2 trillion of US government debt. Japan and China are the largest holders, with around $1 trillion each. The rest is owed to US citizens and businesses, as well as state and local governments.

3. Why is there a borrowing limit?

Before 1917, Congress would authorize the government to borrow a fixed sum of money for a specified term. When loans were repaid, the government could not borrow again without asking Congress for approval.

The Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917, which created the debt ceiling, changed this. It allowed a continual rollover of debt without congressional approval.

Congress enacted this measure to let then-President Woodrow Wilson spend the money he deemed necessary to fight World War I without waiting for often-absent lawmakers to act. Congress, however, did not want to write the president a blank check, so it limited borrowing to $11.5 billion and required legislation for any increase.

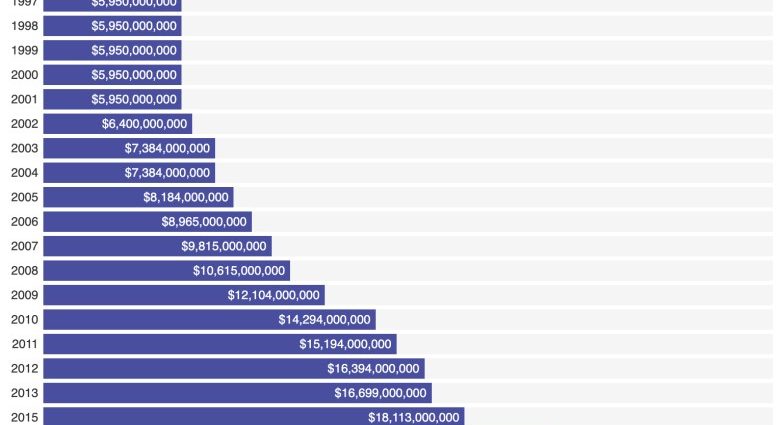

The debt ceiling has been increased dozens of times since then and suspended on several occasions. The last change occurred in December 2021, when it was raised to $31.38 trillion.

4. What happens when the US hits the ceiling?

Whenever the US nears its debt limit, the Treasury secretary can use “extraordinary measures” to conserve cash, which she indicated began on January 19. One such measure is temporarily not funding retirement programs for government employees. The expectation will be that once the ceiling is raised, the government would make up the difference. But this will buy only a small amount of time.

If the debt ceiling isn’t raised before the Treasury Department exhausts its options, decisions will have to be made about who gets paid with daily tax revenues. Further borrowing will not be possible. Government employees or contractors may not be paid in full. Loans to small businesses or college students may stop.

When the government can’t pay all its bills, it is technically in default. Policymakers, economists and Wall Street are concerned about a calamitous financial and economic crisis. Many fear that a government default would have dire economic consequences – soaring interest rates, financial markets in panic and maybe an economic depression.

Under normal circumstances, once markets start panicking, Congress and the president usually act. This is what happened in 2013 when Republicans sought to use the debt ceiling to defund the Affordable Care Act.

But we no longer live in normal political times. The major political parties are more polarized than ever, and the concessions McCarthy gave right-wing Republicans may make it impossible to get a deal on the debt ceiling.

5. Is there a better way?

One possible solution is a legal loophole allowing the US Treasury to mint platinum coins of any denomination. If the US Treasury were to mint a $1 trillion coin and deposit it into its bank account at the Federal Reserve, the money could be used to pay for government programs or repay government bondholders.

This could even be justified by appealing to Section 4 of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution: “The validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned.”

Few countries even have a debt ceiling. Other governments operate effectively without it. America could too. A debt ceiling is dysfunctional and periodically puts the US economy in jeopardy because of political grandstanding.

The best solution would be to scrap the debt ceiling altogether. Congress already approved the spending and the tax laws that require more debt. Why should it also have to approve the additional borrowing?

It should be remembered that the original debt ceiling was put in place because Congress couldn’t meet quickly and approve needed spending to fight a war. In 1917 cross-country travel was by rail, requiring days to get to Washington. This made some sense then. Today, when Congress can vote online from home, this is no longer the case.

Steven Pressman is Part-Time Professor of Economics, The New School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.