Much of Asia getting old before getting rich

It is often said that demographics are destiny, but at a macroeconomic level, aging societies do not need to turn into the economic graveyards that pessimists assert they will. There are important, if limited, coping mechanisms to deal with the predicted stagnation or fall in the working-age population that most countries will face sooner or later.

Public policymakers could aim to raise immigration, boost the labor force participation rates of older workers and women and crank up productivity growth. Several Asian states will have to consider these options much more carefully if they are to adapt, stabilize the working-age population impact of aging and provide for sustainable public finances.

Leaving aside Japan, Australia and New Zealand, which have “aged” — defined as a doubling of the over 65s as a share of the total population to 14% — over half a century or more, most other countries are aging much faster, that is, over 20–25 years. This phenomenon has triggered the now well-known warning of “getting old before getting rich.”

On average, Asia still falls short of the 7% threshold of over 65s as a share of the population, but the United States Census Bureau estimates that by 2060 42 of the 52 countries in Asia will have broken through the 14% level. The bulk of states will proceed to age more rapidly.

Asia has aging hares, like Japan, China and South Korea, as well as tortoises, like India and Indonesia, and offers a disparate group of countries with different aging conditions and varying capacities to address the effects.

Shrinkage in the working-age population is now well-established in Japan, South Korea and China, and others will follow. These aging behemoths are already increasing investment and production in younger Asian economies, like Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia and Bangladesh — for both economic and geopolitical reasons.

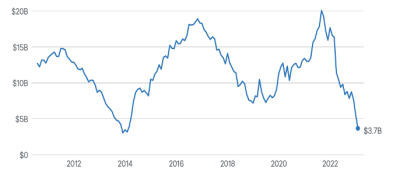

Another striking domestic demographic choke point is the outsized Chinese real estate sector, already buckling under the deadweight of bad debt and overcapacity. The expected 25% fall in the cohort of first-time property buyers over the next decade or two will crimp household formation and housing demand, forcing the sector to shrink.

India’s working-age population, by contrast, is expected to expand by more than the stock of working people in Europe today. Its challenge is to ensure adequate job creation and education for its new cohorts of young workers. This also goes for Indonesia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, but replicating China’s so-called demographic dividend experience may prove difficult.

What then can be done? Immigration is especially sensitive to the political climate. Countries with high immigration rates, such as Australia, New Zealand and Singapore are in a better position to compensate for downward working-age population pressures but even for them, immigration alone will not suffice.

Japan’s tentative opening to higher immigration is notable, but no other countries can look to immigration as a viable contributor to the aging challenge.

Labor force participation experiences are highly diverse, and not always comparable because of poor labor market statistics, exacerbated by the proliferation of informal economies in poorer countries and unpaid care work.

Male labor force participation rates tend to be high at 85–90%, but female rates range from about 30% in Southern Asia to over 80% in parts of East Asia. Apart from tackling cultural and institutional barriers to women in work — which even Japan has moved firmly to counter — the provision of affordable and widely available childcare is a critical success factor.

Labor force participation for older workers in Asia has increased for women — from a lower starting point — but not men. Countries will have to raise the age of pension eligibility to help sustain the working-age population and secure the viability of pension systems. In China, India, Malaysia and Thailand, the retirement age of 60 or less is far too low.

Although Asia’s economic growth is still a beacon in the world economy, its lackluster productivity growth remains a scar from both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

With China set for at least more pedestrian growth if not more troubling headwinds, the search for higher productivity growth becomes all the more important against the backdrop of aging and uncertain supply chains.

Macroeconomic management will also have to accommodate rising public social spending running at about 7% of GDP, or roughly a third of average public social spending in developed market economies. Asian countries have a lot of catching up to do if they try to compensate for weakening familial care and address the needs of the sharp rise in older citizens.

The redistributive power of social programs in much of Asia is limited, either because of low generosity even where coverage rates are high, or because benefits tend to be focused on former workers who had formal employment contracts. But many states have low coverage rates and markedly lower wage replacement rates for women than for men.

There are also widespread disparities in the availability of affordable healthcare. Poorer countries, but also China, have weaker public sector health spending and higher household out-of-pocket expenditures.

The major challenge will be the ubiquitous spread of non-communicable diseases as populations age, potentially mitigated by the promising effects of artificial intelligence on the diagnosis, treatment and care of illnesses.

Demographics are proceeding at different rates, but it is no accident that richer Asian countries are in a better place thanks to better preparation. Countries with flexible social, political and economic institutions, and more ambitious age-related agendas, will come of age more successfully.

The biggest demographic shock for most may be the China–India population cross-over which has occurred this year, with longer-term consequences we can only guess.

George Magnus is Research Associate at the China Centre, Oxford University, and at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. This article was originally published by East Asia Forum and is republished under a Creative Commons license.