Tokyo needs to focus on its role as a middle power

In 2018, we convened the Asia’s Future Research Group because of concern about the intensification of US-China geopolitical rivalry and the increasing risk of military clash in the Asia-Pacific region. The lack of balance in Japanese public discourse about how Japan should address this evolving strategic environment in Asia deeply troubled us.

We saw that not only Asia’s future but also Japan’s future was at a strategic crossroads. We therefore invited scholars and experts on Japanese foreign policy and international relations to join a multiyear project in order to develop a realistic and moderate Japanese strategy for Asia.

In December 2022, the Japanese government adopted a new “National Security Strategy” for the first time in a decade. Although it does not ignore the need for diplomatic dialogue and cooperation, what stands out is the strong emphasis on power politics (including military capabilities) and geopolitics as well as economic security.

The new strategy stresses the centrality of Japan’s self-defense capabilities and the US-Japan alliance. However, there exists a significant disparity between the paradigm presented in the new strategy document and Japan’s own capabilities.

Consequently, the US-Japan alliance is deemed essential to fill this gap; and in that sense, there is an element of logical consistency in the new strategy. Accordingly, strengthening the US-Japan alliance ends up being the strategy’s a priori premise and its absolutely indispensable prescription.

Our serious concern that the new paradigm will leave Asia entangled and divided in the future.

Japan’s long-held emphasis on a multifaceted and multilayered approach to Asia policy continues to be a constructive way to address the new regional and international challenges that have emerged. The transnational challenges that have become particularly prominent in recent years have acutely demonstrated the need for an unprecedented level of international cooperation. Nevertheless, recent foreign policy discourse around the world has tended to focus more on great power competition than on interstate cooperation.

In this context, Japan should maintain and promote security cooperation with the United States – but at the same time, it should also exercise leadership to help mitigate the competition between the US and China in Asia through constructive diplomacy, thereby reducing the danger of great power war in the region. Without this, there can be no solution to transnational problems and no progress toward a world free of nuclear weapons.

Such efforts and practices are consistent with the concept of “middle power diplomacy,” which aims toward a more autonomous foreign policy – one that is close to, but not solely

dependent on, the United States.

Approach toward Asia and the promotion of middle power diplomacy

One of the most important goals of Japan’s policy toward Asia is to promote further prosperity in the region through international trade, investment, and technological advances while making economic activities more environmentally sustainable and ensuring that the benefits of economic development are distributed more equitably.

To achieve this future vision, cooperation with countries that share values and similar political and economic institutions is crucial. Relations with the United States remain an important pillar of Japan’s foreign policy. However, using the rationale of strengthening the US-Japan alliance, Japan should not neglect countries that are not allies or partners of the United States.

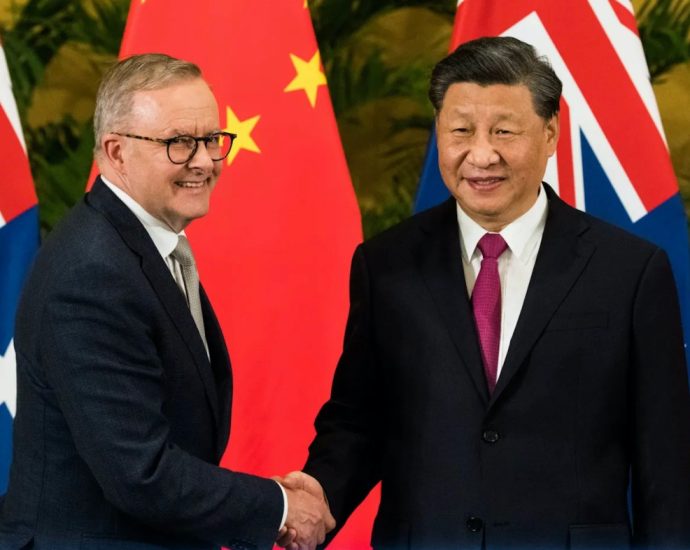

To mitigate great power competition and prevent it from escalating into great power wars, Japan should deepen cooperative relationships with middle powers in the Asian region, such as South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and become a driving force of middle power cooperation.

While defending fundamental human rights and democratic principles, Japan should recognize the diversity of political systems in Asia and be sensitive to the different historical trajectories and sociocultural traditions in each country. Japan should resist moves to divide Asia into a struggle between democracies and autocracies and avoid an overly ideological approach to foreign policy.

Japan should also be cautious about defining the Asian region solely in terms of the “Indo-Pacific,” a concept that has recently been used frequently in international political

discourse.

While the concept of the Indo-Pacific has the advantage of emphasizing the importance of freedom of navigation and the security of long sea lanes vital to international trade, it has the drawback of viewing the Asian region primarily in maritime terms. The Indo-Pacific concept diminishes the importance of continental Asia and suggests an intention to counter or contain China.

Rather than concentrating on a single geographical concept, Japan’s diplomacy should reflect a multifaceted view that also incorporates the perspectives of “AsiaPacific,” “East Asia” and “Eurasia.”

Japan should reinvigorate its middle power diplomacy to build a more stable, peaceful and prosperous future for Asia. South Korea, which shares basic strategic interests and political values, is Japan’s most important partner in middle power diplomacy.

Japan can also build on the meetings involving Japan, Australia, India, and the United States – the Quad meetings – and take the lead in promoting a “middle power coalition” of Japan, Australia, and India. Inviting other Asian middle powers, such as South Korea and the ASEAN nations, to the mix would lead to the formation of a region-wide middle power alignment.

Japan should energetically engage China on the basis of partnerships with middle power countries in Asia and Europe to achieve stability in bilateral relations between Japan and China and cooperation on urgent transnational issues.

Regional economics

The Asian region has achieved remarkable economic development since World War II. At the same time, economic liberalization and rapid globalization that have driven this development have brought to the surface problems such as widening economic disparities and environmental degradation.

To mitigate such side effects and socio-political costs, Japan must place greater emphasis on sustainable development goals, which focus more on social and environmental protection.

In addition, the negative impact of the Covid-19 global pandemic and the disruption of international supply chains due to the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as China’s “weaponization of trade” and economic coercion have become prominent as new challenges of economic security.

Devising an effective response to these challenges is now an urgent priority for Japan and many Asian countries. Therefore, Japan’s regional economic diplomacy requires policies from three separate perspectives: economic liberalization, sustainable development and economic security.

Japan has played an important role in the Asian region in areas such as financial governance, trade promotion and development assistance cooperation, including infrastructure development. Building on this past success, Japan should continue to play a leadership role in rule making and cooperation in each of these areas as a leading economic power in Asia and a global middle power.

For example, Japan can make a meaningful contribution to implementing and expanding the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which is widely regarded as a high-standard free trade agreement in terms of trade liberalization and order building.

It can also help to devise an effective international debt restructuring program for Sri Lanka, which defaulted last year.

In the area of infrastructure development, Japan should continue to promote and realize its proposal to standardize the international principles of “quality infrastructure investment.” Encouraging China to follow these principles would help steer China’s investment

and support for infrastructure development toward sustainable economic development in the developing countries in Asia.

In addition, while various frameworks for regional economic cooperation exist in Asia, Japan’s basic position should be “open regionalism” and the prevention of a fragmented Asia.

From this perspective, Japan should promote cooperation under the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), as a founding member. But Japan should also consider joining the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA), which was launched by small and medium-sized Asia-Pacific countries (Singapore, Chile, and New Zealand) and is expected to expand its membership in the future, as well as the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Regional security

In order to maintain peace in Asia and to uphold Japan’s security, a certain level of deterrence is essential, but this raises the potential of a security dilemma. For deterrence to be effective, it is necessary not only to properly develop defense capabilities but also to provide some assurance to potential adversaries that their core interests will not be threatened.

Also, in pursuing defense cooperation between Japan and the United States, Japan should not hesitate to actively and openly express its views on security issues to the United States. A healthy alliance is not one in which Japan simply submits to US policies and intentions, but rather one in which Japan confidently engages in strategic dialogue with the United States on a more equal footing.

Regarding various Asian security issues, Japan should skillfully balance deterrence and diplomacy and pursue policies that contribute to reducing tensions and preventing crises.

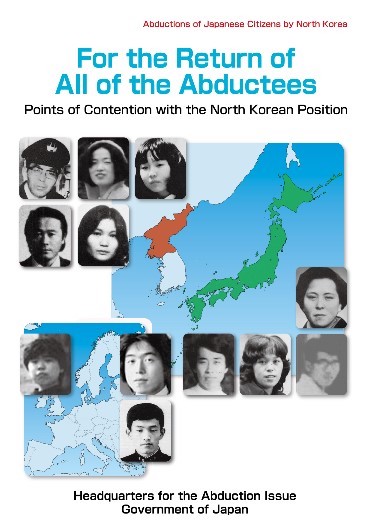

With regard to North Korea, Japan should seek a realistic, gradual, reciprocal and step-by-step approach toward the ultimate goal of denuclearization of North Korea by making concrete progress on the resolution of the abduction issue.

With regard to the Taiwan issue, it is necessary to avoid a military crisis by maintaining conditions under which the status quo is preserved until the day comes when China and Taiwan can find a peaceful solution to the unification issue. To this end, it is important that both Japan and the United States convey to China in a credible manner that they clearly oppose any unilateral use of military force by China and at the same time have no intention of supporting Taiwan’s permanent separation or independence from China.

Meanwhile, the Senkaku Islands issue is one of the major factors undermining stability and cooperation in Sino-Japanese relations, and Japan should be creative in discussing with China various ideas for reducing tensions over those islands. Japan should politically revive and try to implement the Japan-China joint press release of June 2008 and the understanding on joint development in order to make the East China Sea a “sea of peace, cooperation, and friendship.”

The first pillar of Prime Minister Kishida’s “Hiroshima Action Plan” is the continued non-use of nuclear weapons. To strengthen this pillar, the Japanese government should publicly urge the nuclear weapon states to adopt a doctrine of “no first use” of nuclear weapons. By doing so, it will help institutionalize a global norm against the use of nuclear weapons.

By participating as an observer in the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, Japan can demonstrate international leadership toward nuclear disarmament as a long-term goal. Japan’s participation as an observer would not undermine US nuclear deterrence but rather serve as a bridge between the nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states.

Transnational challenges

Japan has heretofore made considerable contributions through international organizations and bilateral aid to address transnational issues such as global warming, pandemics of infectious diseases, and refugees from conflict in unstable regions. Based on this track record, Japan should continue to demonstrate its leadership in this area as a responsible major Asian country and a leading global middle power.

In addition, as an economically developed liberal democracy, Japan has an international responsibility to defend and promote universal human rights. In this regard, the concept of “human security,” which Japan has long advocated, is effective in dealing with these transnational challenges in Asia, where many countries tend to emphasize national sovereignty and a variety of political systems exist.

Therefore, Japan needs to promote more inclusive and effective regional and international cooperation, while keeping this concept as a basic principle and acting as a bridge across the geopolitical and ideological divides that have become more pronounced in recent years.

Specifically, Japan should work with other Asian countries to ensure that public health cooperation, such as Covid-19 vaccine provision, is not unnecessarily drawn into the intensifying Sino-American strategic competition.

On climate change, given that both Japan and China are major carbon emitters in Asia, Japan should directly cooperate with China in the development and promotion of environmental technologies. This would not only enhance their ability to meet their own emission reduction targets, but also contribute to helping other Asian countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

In the area of human rights and humanitarianism, Japan should first and foremost improve its own human rights and human security situation and lead by example. While refraining from bringing up human rights and democracy as ideological tools in the geopolitical competition with China, Japan should adopt practical humanitarian approaches that are in line with local realities.

For example, through existing frameworks such as the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, Japan can share best practices with other countries on improving government transparency and reforming legal and judicial systems and foster and support civil society actors involved in providing humanitarian assistance to victims of human rights abuses.

Major recommendations

Based on the above ideas, here are our specific recommendations for Japanese policy toward Asia:

- In order to develop middle power diplomacy, lead the promotion of a “middle power coalition” of Japan, Australia, and India, which could drive the agenda-setting of the Quad (Japan, Australia, India, and the United States), and further strengthen functional cooperation with the Republic of Korea, ASEAN, and other middle power countries.

- In response to the South Korean government’s decision regarding the “conscripted labor issue,” make continuous efforts to improve relations with South Korea.

- Regarding debt restructuring measures for Sri Lanka, encourage China to participate continuously in the newly established “Creditor Committee for Sri Lanka” and cooperate by disclosing necessary information.

- Encourage the return of the United States to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and make diplomatic efforts toward the goal of simultaneous accession of China and Taiwan, which have formally applied for membership.

- Explore the appropriate timing with a view to joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

- With regard to rulemaking in the digital sector, consider applying for membership in the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA), while promoting cooperation in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF).

- Strengthen and deepen the doctrine of strictly defensive defense in the direction of enhancing deterrence by denial rather than focusing on counterstrike capabilities, which are less effective and have greater side effects.

- Encourage North Korea to conduct another investigation into the abduction victims and establish a liaison office in North Korea to carry out such an investigation, with the aim of resuming negotiations for the normalization of diplomatic relations with North Korea.

- Since a gradual, realistic, incremental, and reciprocal approach is needed to achieve the ultimate goal of denuclearization of North Korea, seek as a first step a freeze of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile development programs.

- Based on paragraph 3 of the 1972 Japan-China Joint Statement, while opposing unilateral changes in the status quo from either side of the Taiwan Strait, clearly state that Japan does not support Taiwan’s independence.

- Acknowledge the reality of the existence of an issue between Japan and China regarding the Senkaku Islands and discuss with China ways to ease and resolve tensions over the islands.

- Urge the nuclear-weapon states to adopt a doctrine of “No First Use” of nuclear weapons and participate as an observer in the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

- Encourage inclusive transnational cooperation in the public health sector and work to reduce the negative impact of geopolitical tensions, ideological differences, and sovereignty conflicts on such cooperation.

- Cooperate with China to promote environmental technologies and develop low-carbon infrastructure in third-country markets to address the climate change crisis in Asia.

- Regarding human rights and human security, focus on improving the human rights situation at home while promoting a non-ideological, humanitarian approach that is practical in line with local realities in order to broaden support and cooperation among Asian countries

This article is excerpted with permission from the report “Asia’s Future at a Crossroads: A Japanese Strategy for Peace and Sustainable Prosperity,” published this week by the “Asia’s Future” Research Group. The group’s convenors are Yoshihide Soeya, professor emeritus of political science and international relations at at the College of Law of Keio University, and Mike Mochizuki, who holds the Japan-U.S. relations Chair in Memory of Gaston Sigur at the Elliott School of International Affairs of George Washington University and is also a non-resident fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

Other authors and editors are Kuniko Ashizawa, who teaches international relations at the School of International Service, AmericanUniversity, and at the Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University; Miwa Hirono, a professor at the College of Global Liberal Arts at Ritsumeikan University; Saori Katada, a professor of international relations and the director of the Center for International

Studies at the University of Southern California; Kei Koga, an associate professor at the Public Policy and Global Affairs Program, School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, and concurrently a nonresident fellow at the US National Bureau of Asia Research and a member of the Research Committee at Japan’s Research Institute for Peace and Security; Jong Won Lee, a professor at the Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies, Waseda University; Kiyoshi Sugawa, a senior research fellow at the East Asian Community Institute; Takashi Terada, a professor of international relations at Doshisha University; Ambassador Kazuhiko Togo, a visiting professor at the Global Center for Asian and Regional Research, University of Shizuoka; and Hirotaka Watanabe, a professor at the Department of Political Science, Teikyo University.