Unraveling Pakistanâs economic crisis

Pakistan is on the brink of an economic meltdown that threatens the nation’s fragile financial credibility and paves the way for potential political, humanitarian, and social upheaval.

Marked by widespread civil-disobedience movements, dwindling foreign-exchange reserves, soaring prices of essential commodities such as wheat, onions, milk and meat, persistent power blackouts, and an upcoming election, Pakistan faces a perfect storm of challenges.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s government is grappling not only with internal political turmoil resulting from the ousting of the administration led by Imran Khan but also external pressures from intergovernmental agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

A struggling economy

The disruptions caused by the pandemic had a severe impact on economies worldwide, including Pakistan. Supply-chain disruptions affected various sectors, from retail to automobile manufacturing.

The resurgence of Covid-19 in China, the world’s second-largest economy and a significant player in global value chains across South and Southeast Asia, has added to the spillover effects on the global economy.

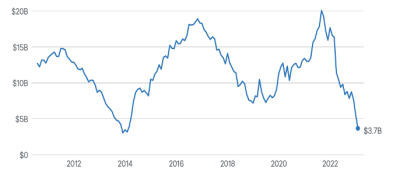

Consequently, by February, Pakistan’s foreign-exchange reserves hit an unprecedented low of US$3.19 billion, enough to cover only two weeks of import expenses, falling significantly short of the IMF’s mandated three-month import cover.

The situation is further aggravated by Pakistan’s daunting task of repaying a massive debt of $73 billion by 2025, amid a volatile political landscape and uncertain reliability of lending nations. The country’s total debt burden of $126 billion consists mainly of external loans obtained from China and Saudi Arabia.

Figure 1: Trends in Pakistan’s Foreign Reserves

Security concerns stemming from violent separatist groups in Sindh and Balochistan have strained the strong relationship between Pakistan and China, possibly causing the latter to suspend its developmental initiatives under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

This further hurts Pakistan’s international reputation, as it is already considered a breeding ground for terrorism, hampering its prospects for foreign investment and assistance.

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has been a relatively stable supporter, except for occasional demands for immediate debt repayment.

While the relationship between the Saudi royal family and Pakistan has evolved into a strategic partnership, with Pakistan strengthening Saudi Arabia’s military and Riyadh making critical investments in Pakistan, the future of this friendship is undeniably based on geopolitical and religious interests.

Endless debt

Pakistan’s historical and cultural ties with its key allies, China and Saudi Arabia, run deep despite present circumstances suggesting otherwise.

China’s involvement in Pakistan’s development and trade dates back to the 1960s when Beijing extended interest-free credit of around $85 million (equivalent to several billion dollars today) for technological and infrastructural projects. Bilateral trade agreements were also signed to accelerate industrialization in Pakistan after the Sino-Indian war.

China and its commercial banks account for about 30% of Pakistan’s total external debt, exceeding $100 billion. This proportion surpasses the financial support received by debt-ridden Sri Lanka from China, which accounts for 20% of its total public external debt.

Moreover, the recent disbursement of an additional $700 million from the China Development Bank (CDB) in early 2023 further amplifies Pakistan’s burden of external debt obligations this year.

Figure 2: Pakistan’s Total External Debt (in US$ million) from 2006 to 2022

Pakistan’s chances of defaulting on its foreign obligations this year are more imminent than ever. The nation’s dollar-denominated bonds have reached an all time low. This problem is exacerbated by the country’s low foreign-exchange reserves and upcoming repayments amounting to $7 billion in the coming months.

Additionally, negotiations with the IMF for a bailout have been slow and uncertain, leading to failure to avert a debt default and stabilizing sharply declining bond prices, which have fallen by about 60%.

Pakistan’s reliance on external loans, primarily from China and Saudi Arabia, has further compounded its economic challenges.

While these alliances have historically been strong, recent security concerns in such regions as Sindh and Balochistan have strained the relationship with China. The threat posed by violent separatist groups not only endangers the safety of Chinese nationals but also jeopardizes the future of key developmental initiatives under the BRI and CPEC.

Granting permission for Chinese security firms to operate within Pakistan would come at the expense of the Pakistan Army’s ability to protect foreign nationals.

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia has been a long-standing partner for Pakistan, providing critical support in various sectors. However, occasional demands for immediate debt repayment add to Pakistan’s financial strain, making it challenging to maintain a stable economic trajectory.

In conclusion, Pakistan finds itself at a critical juncture, with its economy on the verge of collapse. The country’s fragile financial credibility is at stake, and the consequences could be far-reaching, affecting not only the economy but also the political, humanitarian, and social fabric of the nation.

It is imperative for the government to address the internal political turmoil and effectively navigate the external pressures from intergovernmental agencies.

Additionally, a thorough evaluation of Pakistan’s foreign partnerships, particularly with China and Saudi Arabia, is necessary to determine their viability and ensure a sustainable path forward.

A more detailed article by this author can be found here: Debt ad Infinitum: Pakistan’s Macroeconomic Catastrophe.