Within pockets of an ever-growing Asia – particularly in the Southeast – the superpowers U.S. and China are jostling to cement influence.

More than ten years ago, former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for a “pivot to Asia”, emphasising a growing focus on the continent as China’s rise took a more centre-stage position within her country’s diplomatic playbook.

Fast forward to now, where, for the first time in three years, a U.S. ambassador to ASEAN confirmed by the Senate has finally stepped into the fold. He comes bearing a reminder for Southeast Asia that the U.S. is eager to maintain its influence in the region.

“The U.S. is all in on Southeast Asia. We’re committed to being a durable and reliable partner,” Ambassador Yohannes Abraham told Southeast Asia Globe.

The ambassador highlighted the commitment of President Joe Biden’s administration to Southeast Asia through two leader-led engagements. These have consisted of the first ASEAN-U.S. Special Summit and Biden’s visit to Phnom Penh last November, which led to the launch of a comprehensive strategic partnership with ASEAN leaders.

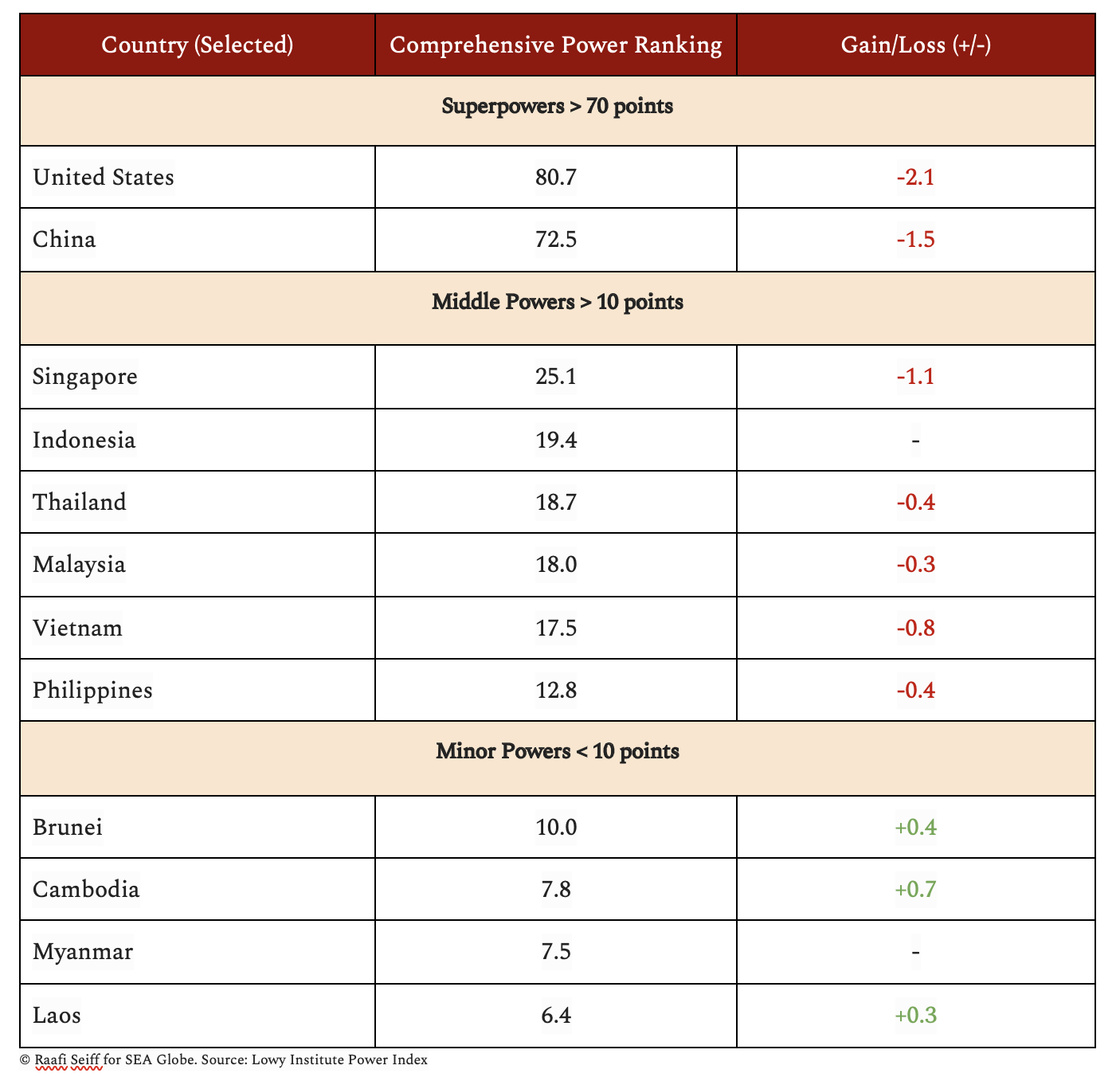

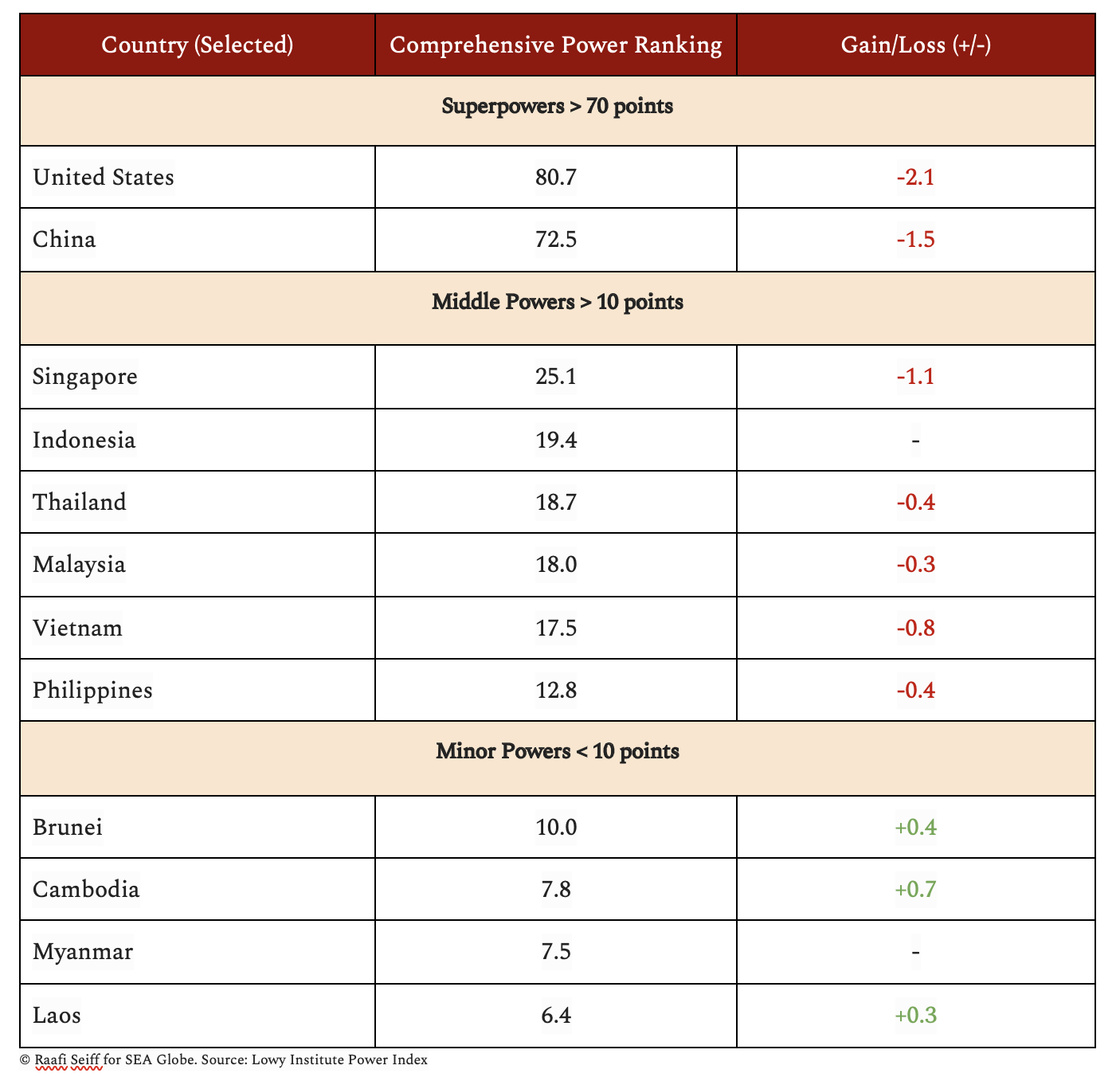

Last month, the Australian think tank Lowy Institute released its annual Asia Power Index that aims to determine which country has the most influence in Asia. The index ranks countries and weighs them based on “comprehensive power” through multiple factors ranging from economic capability to economic relationships, from military capability to cultural influence.

The Lowy index is by and large a comparative list, sizing up power players exerting influence in Asia. At the same time, the index shows how much – or consequentially, how little – countries in Southeast Asia fare individually against the backdrop of Asia.

Launched in 2018, the index has always shown that the U.S. continues to dominate amongst other countries in Asia, with China constantly made second fiddle.

Rivalry between these two will most likely continue. What is most striking however is that through the Lowy index, the collective power of Southeast Asian nations ranks higher than the U.S. or China. Furthermore, against the political skirmish between Washington and Beijing, Southeast Asia is best positioned to overtake both powers and serve as a bridge to a diverse and growing region.

Analysis from the Lowy Institute has called Southeast Asia’s capacity “diplomatically dynamic”, where even smaller countries have the potential of exercising influence. This is an understatement that acknowledges Southeast Asia’s growth but downplays just how much this can mean for the future of Asia.

With a total population of more than 675 million people, a $3 trillion dollar economy and collective growth projected at 5.3% at 2023, Southeast Asia is more than just a political debutante but a force of nature that is able to chart the course for Asia at large. However, unlocking and maximising the region’s potential at the world stage is equally rife with its own challenges. These are mostly due to the countries’ individual domestic affairs accelerated by increased political tensions in the ramp-up to multiple elections, supply chain disruption, a retained “tech winter” and rising inflation rates worldwide.

The index’s key findings show that more than half of ASEAN member states are placed under the category of middle powers. Meanwhile, Cambodia, Brunei and Laos, while not particularly influential on their own, found the greatest annual gains within the index.

Institutionally, ASEAN dates back to 1967 and consolidates values under the pillars of mutual economic prosperity, political-security and socio-cultural affairs.

However, critics might call the regional bloc out as weak and toothless, which has invariably become a defining characteristic of ASEAN due to the bloc’s priority of consensus-building and staunch avoidance of sensitive issues. This is because there are no certain means to keep each ASEAN member accountable. Although institutions, committees or mechanisms can be created, such efforts are futile without resounding political will from its members.

In addition, fighting for the interests of a regional bloc is difficult in regards to the varying political situations across the region. Myanmar is not escaping its own civil war anytime soon, the Philippines has given the keys of the Malacanang Palace back to the Marcos dynasty and Indonesia’s Elections Commission (KPU) is currently gearing up its case to fight a judge’s ruling that might delay the country’s general elections. This is all happening alongside the fact that ASEAN members are operating on extremely different levels of economic strength.

Perception plays a big role in determining Southeast Asia’s direction and, although the U.S. was able to trump China in Lowy’s Power Index, a recent survey conducted by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute shows that Southeast Asians view China as the most influential economic and political power within the region.

A study from the Pew Research Center shows that Singapore and Malaysia have a more favourable view of China than that of the U.S. Worth noting however is that at the end of the day, Southeast Asians are most concerned about ASEAN’s ineffectiveness and the notion that ASEAN can potentially become an arena of major power competition.

In the popular television series Game of Thrones, the fictional world that the characters inhabit is perpetually locked in conflict between factions vying to take the famous Iron Throne, mostly through bloodshed in service to the ruthless pursuit of power. In Southeast Asia, efforts to maintain influence are more covert, and reluctance in taking any controversial stance is clear because each country, more or less, is busy fighting dragons of their own.

In his remarks to the Globe, Ambassador Abraham echoed Biden’s sentiment where “much of the future will be written by this [Southeast Asia] part of the world”. But the questions remain: by who and for who?

Should Southeast Asia be able to secure stability and, more importantly, serve as a model for good governance, a strong and firm ASEAN can potentially shift existing power structures and give the U.S. and China a run for their money.

Raafi Seiff is a policy researcher and director at Policy+, an emerging think tank which seeks to promote good governance and human rights.