China’s expanding naval presence in the Pacific Ocean and the South and East China Seas has become a major focus for Australia, the US and its allies.

Australia’s latest strategic defense review, for instance, was prompted, in part, by the rapid modernization of China’s military, as well as its increasing naval presence in the South China Sea.

According to the US Department of Defense’s most recent annual report to Congress, China’s navy has been strengthened with the addition of 30 new warships over the past 12 months. By 2030, the total number of ships is expected to increase to 435, up from the current 370.

But China is not the only potentially adversarial maritime power that is flexing its muscles in the Indo-Pacific region. Russia is becoming a cause for concern, too, even though the 2023 strategic review did not mention it.

My latest research project, Battle Reading the Russian Pacific Fleet 2023–2030, recently commissioned and published by the Royal Australian Navy, shows how deeply the Russian military is investing in replenishing its aging, Soviet-era Pacific Fleet.

Between 2022 and October 2023, for instance, it commissioned eight new warships and auxiliaries, including four nuclear-powered and conventional submarines. On December 11, two new nuclear-powered submarines formally joined the fleet, in addition to the conventional RFS Mozhaisk submarine, which entered service last month.

These figures may not look as impressive as the new Chinese vessels mentioned above, but it’s important to recognize that the Russian Navy has the unique challenge of simultaneously addressing the needs of four fleets (in the Arctic and Pacific oceans and Black and Baltic seas), plus its Caspian Sea flotilla.

Furthermore, Russia’s war in Ukraine has not had a considerable impact on the Pacific Fleet’s ongoing modernization or its various exercises and other activities. Between early 2022 and October 2023, for instance, the Pacific Fleet staged eight strategic-level naval exercises, in addition to numerous smaller-scale activities.

Rebuilding its powerful navy, partnering with China

In addition to rebuilding its once-powerful navy, the Russians are committing enormous resources to building up naval ties in the Indo-Pacific and strengthening their key maritime coalitions.

In recent months, for instance, a naval task group of the Pacific Fleet embarked on a tour across Southeast and South Asia. This tour made international headlines but was effectively overlooked by the Australian media.

The Russian warships spent four days in Indonesia, then staged their first-ever joint naval exercises with Myanmar and another exercise later with India. The ships then visited Bangladesh for the first time in 50 years, followed by stops in Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

The tour signals a widening of Russia’s scope in the region, though its most important naval partner remains China.

According to my findings, between 2005 and October 2023, the Russian and Chinese navies have taken part in at least 19 confirmed bilateral and trilateral (also involving friendly regional navies) exercises and three joint patrols.

The most recent was carried out in mid-2023, when the Russian and Chinese joint task force was deployed to the North Pacific, not far from the Alaskan coast.

Canberra’s preoccupation with China should not make us blind to other potential adversaries that could threaten our national security in the medium to long term.

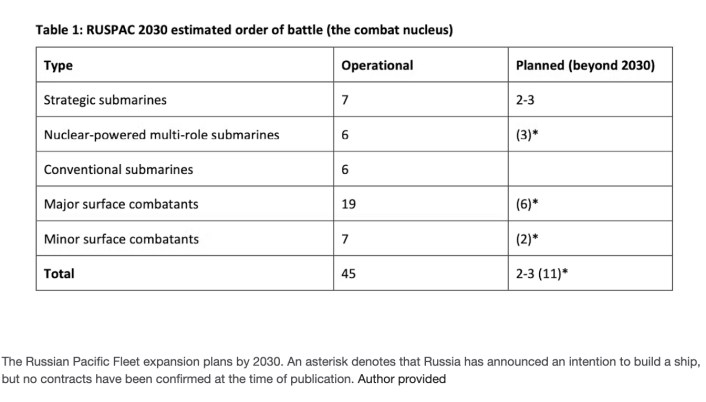

According to my estimates, by the time the Royal Australian Navy commissions its first Hunter class frigate and the first Virginia-class, nuclear-powered attack submarine begins operations in 2032, the replenished Russian Pacific Fleet would have a battle force of at least 45 core warships.

This is expected to include 19 nuclear-powered and conventional submarines, supported by minor combat and auxiliary elements. Most of these units would be newly designed and built.

This clearly shows that if war someday breaks out in the Pacific, the Russian Pacific Fleet could present a formidable challenge to Australian and allied naval fleets in the western and northwestern Pacific, as well as the Arctic.

Australia’s decision to acquire nuclear-powered platforms from the United States and United Kingdom suggests our intent to support and engage in long-range maritime operations with our allies, possibly as far as the northern Pacific and Arctic oceans.

And in times of crisis short of open war, Russia will also have more assets to support operations around Southeast Asia and in the Indian Ocean, extending its reach closer to the Royal Australian Navy’s areas of immediate concern.

Finally, the deepening naval cooperation between China and Russia could become a risk factor in its own right as the two countries seek to counter the AUKUS security pact. This is especially true with the possibility of expanded joint naval operations in the Pacific.

Despite the tyranny of distance between Australia and Russia, we are no longer irrelevant in Moscow’s strategic planning. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu made this clear in recent remarks blasting AUKUS as a threat to stability in the Asia-Pacific region.

This means Australia’s navy and its maritime ambitions are increasingly being viewed as a risk factor to the Kremlin.

During the Cold War confrontation in the Asia-Pacific, the Soviet Union’s naval power in the region was a primary point of strategic concern for Australia, the US and its allies. This is once again proving to be true.

Alexey D Muraviev is Associate Professor of National Security and Strategic Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.