In April 2023, Asia Times released a study of US trade dependencies under the title, “The Great Re-Shoring Charade.” We found that the United States imported less from China only because it imported more from countries dependent on Chinese semi-finished goods, components and capital goods.

In effect, America’s “friend-shoring” partners assembled finished goods out of imported Chinese components and shipped them on to the United States.

Despite the Trump tariffs and the Biden Administration’s commitment to “re-shoring,” China’s dominance of global supply chains in manufacturing has grown, not shrunk, during the past several years. That’s because capital investment in US manufacturing continues to shrink.

In the meantime, the research departments of several major institutions have confirmed our results in painstaking detail. These include the International Monetary Fund, the Bank for International Settlements, and the Peterson Institute, a private think tank in Washington.

IMF economists wrote on November 1, 2023:

While US-China decoupling in bilateral trade is real, supply chains remain intertwined with China. Over the period, China’s share of US imports fell from 22% to 16%. The paper shows that the decline is due to US tariffs. US imports from China are being replaced with imports from large developing countries with revealed comparative advantage in a product. Countries replacing China tend to be deeply integrated into China’s supply chains and are experiencing faster import growth from China, especially in strategic industries. Put differently, to displace China on the export side, countries must embrace China’s supply chains.

A team of researchers at the Peterson Institute wrote on Sept. 3, 2023:

For the United States, a goal of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework is to establish a network of “trusted partners” in Asia to reduce reliance on China.

But diversifying the region’s supply chains – an objective repeated by Treasury secretary Janet Yellen during her Beijing visit in July – could prove elusive. Analysis of data from bilateral trade flows from 2010 to 2021 provides clear evidence that IPEF diversification goals push against long-term market trends. IPEF countries now rely more heavily on a smaller set of import sources and export destinations than they did a decade ago, and their import and export patterns have become far less diversified across partners, most notably for middle-income countries emerging as alternative sites for production currently located in China.

And in October, Bank for International Settlements researchers published an examination of supplier and customer relationships at the firm level, concluding:

Firms from other jurisdictions have interposed themselves in the supply chains from China to the United States. The identity of the firms that have interposed themselves in this way can be gleaned from the fact that firms from the Asia-Pacific region account for a greater portion of suppliers to US customers than in December 2021, as well as accounting for a greater portion of the customers of Chinese suppliers.

All of these studies used different methodologies. The Bank for International Settlements effort is the most comprehensive, using supplier and customer data at the level of individual firms in all the major sectors of manufacturing. The Asia Times study, the first to appear, employed time-series analysis, comparing China’s exports to intermediary countries with those countries’ exports to the United States, a simple but robust methodology.

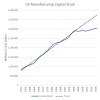

China’s growing dominance of global supply chains is the result of chronic US underinvestment in manufacturing. In constant dollars, US manufacturers’ orders of nondefense capital goods (excluding transportation) are where they were twenty years ago. Meanwhile imports of capital goods (also in constant dollars) have grown more than fourfold in the past twenty years. The US now imports more capital goods than it makes at home.

If the US set out to increase domestic output in order to reduce its $400 billion a year trade deficit with China, it would first have to import more capital goods.

America’s capital stock of manufacturing equipment has barely changed since the recession of 2000. In current dollars, the difference between the long-term trend and the stagnation of the past twenty years adds up to roughly $1 trillion – almost five years’ worth of total corporate spending on manufacturing equipment.

Until the United States invests in manufacturing technology, infrastructure and education, its dependency on Chinese supply chains will only grow. It should be no surprise that re-shoring turns out to be a charade, a soporific offered by politicians in place of a real solution.