Ben Golub, an economics professor at Northwestern University, tweeted the following the other day:

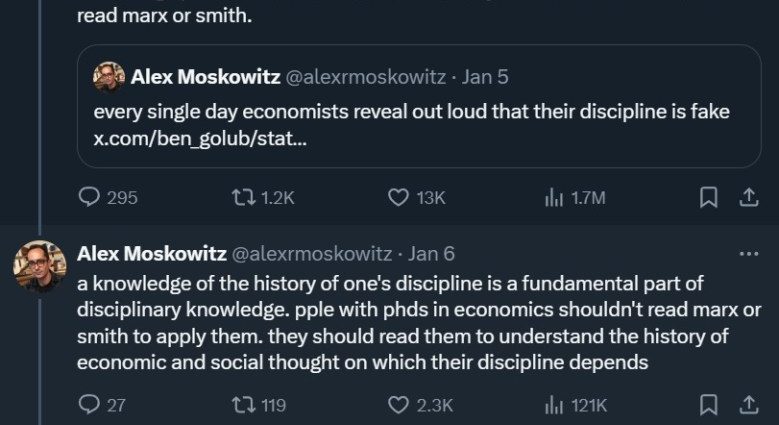

Mount Holyoke English teacher Alex Moskowitz responded to the discovery that most economists don’t learn Smith and Marx by , calling finance “fake”,  , declaring , that it “hasn’t effectively historicized its own techniques of knowledge creation”:

Moskowitz is correct, correct? If economists all be required to learn, “work through”, and know Adam Smith and Karl Marx? Because the majority of people haven’t done this, is the skill “fake”?

First of all, it’s important to point out that studying history of thought isn’t usually helpful. Just as physicists typically don’t read Isaac Newton’s works of art or study John Nash’s unique documents to know game hypothesis, doctors typically don’t study the functions of Galen.

The most important concepts in scientific remain single, divorced from the thought procedure of their progenitors. Everyone can simply pick up Newton’s Laws or Nash Equilibrium and use them to solve real-world problems, without knowing where those instruments came from. This is why they’re but effective.

Think you’re an analyst working for Amazon, using sport theory to layout online markets. Now imagine that an English teacher at a liberal arts college tells you that your entire area is “fake” because you haven’t read Marx. I imagine that practice would be a little strange.

Let’s leave off the topic of whether and when economists should study the history of financial idea and point out that they do examine it as well, just not in the manner that Alex Moskowitz may want.

When I was an economics PhD student, I was assigned a whole bunch of old foundational papers that were influential in framing modern economic thinking. To illustrate what the economics canon actually entails, I’ll give four examples:

1. Paul Samuelson’s ( 1958 )” An Exact Consumption-Loan Model of Interest with or without the Social Contrivance of Money.”

In economics, there’s an important kind of model called the “overlapping generations” or , OLG model, which is basically a model of how old people, young people, and middle-aged people interact in the economy. In terms of those generational interactions, you can think about a lot of economic phenomena.

For example, young people generally have to borrow to get started in life — student loans, starter homes, cars, and such. People work and save when they’re middle-aged and young, and then have to spend down their wealth when they retire. This creates some interesting interactions because the old people can only consume by selling their accumulated assets — houses, stocks, etc. — to the younger and middle-aged population.

Paul Samuelson wasn’t the first to think about this, but he was the first to formulate it in a really simple mathematical model that a lot of people could work with — and which is still , commonly used today. He demonstrated in this paper that if there was rapid population growth, problems could arise because there were so many young people who needed to borrow more than the younger generation could lend. In this case, the best thing to do would be to transfer money from each young generation to each old generation in turn, so they’d have enough money to lend each other.

You might be able to identify this as the fundamental tenet of Social Security.

2. Paul Samuelson’s” The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure” ( 1954 ) is the author of.

One of the most important concepts in public economics is the idea of a , public good , — something that the private sector won’t provide enough of on its own, and so which the government ought to provide ( if it can ). Paul Samuelson was not the first to consider this broad concept, either, but like with the OLG model in the previous example, he was the first to provide a mathematical illustration of how this might operate.

In this paper, he shows that if something is , “nonrival”  , ( if one person using something doesn’t stop someone else from using it ) and , “nonexcludable”  , ( if you can’t prevent people from using it )— then the private sector won’t build enough of it. A lighthouse is a classic example, because using one ship doesn’t necessarily mean stopping others from using it because everyone can see the light and you can’t really stop any particular ship from using it. So building a lighthouse is a dicey investment for any private company— you’re basically encouraging a whole bunch of free riders.

The economics profession debates the solution, and whether it’s to have the government step in and build the lighthouse or whether there’s a private arrangement that could work just as well. And whether you actually need both nonrivalry and nonexcludability in order to get some of the key features of public goods is another open question. However, Samuelson’s original paper essentially predominated the literature on public goods, so its influence is difficult to overstate.

3. George Akerlof’s ( 1970 ) book” The market for lemons” is a good example.

Anyone who has bought a new car knows that when you drive it off the lot, the resale price instantly drops far below the purchase price. Why? It’s the same car that it was an hour ago! People will assume something is wrong with a car if you try to sell it right away after buying it, according to the most likely response.

This insight was the basis for Akerlof’s paper. It’s about how markets can naturally deflate as a result of asymmetric information, which sellers are aware of but buyers are not. In the case of used cars, the process is called “adverse selection” — meaning that sellers want to sell low-quality stuff for more than it’s really worth by concealing how crappy it is.

Akerlof demonstrated how a buyer’s refusal to accept full payment for a used car may lead to a “lemon,” which is why used car dealers keep their high-quality vehicles completely off the market. He used some simple mathematical examples to illustrate this.

How do you solve the lemon problem? Paying for mechanics to check whether a car is in good condition is one option, but that also costs money. Another way might be for the government to pass laws requiring used car dealers to tell prospective buyers important information about a car’s quality.

There is a clear use for health insurance as well. Adverse selection can also happen when a buyer conceals information from a seller, insurance customers will naturally try to hide how sick they are from an insurer, in order to get a lower premium.

This results in healthy people having to pay too high premiums, which keeps them off the market. Laws like the Affordable Care Act ( Obamacare ) that penalize people for not buying health insurance are aimed at preventing the exit of healthy people from the market, based on exactly the kind of principle Akerlof talks about in his paper.

4. ” Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care”, by Kenneth Arrow ( 1963 )

This one is intriguing because, despite the author’s fame for mathematical economics, this paper essentially consists of no math; rather, it’s just an essay making various logical arguments. Arrow is trying to explain why health care — including health insurance — isn’t like other markets. He basically just gives a number of reasons why health care is different. These reasons include:

- People with more insurance may be more reckless, but there are also information asymmetry, the aforementioned adverse selection, and “moral hazard” ( i .e., people with more insurance may be more reckless ).

- Health care involves , extreme risks, including the risk of death. Arrow implies, but doesn’t specify, that both patients and providers may not be competent to make wise decisions in that kind of extreme uncertainty.

- Humans have strong , moral norms , around health care — we tend to believe that basic medical care is a universal a human right, that doctors shouldn’t act like profit-seeking businesspeople, a moral disgust at the idea of forcing people to pay for health care before they receive it, and so on.

- Externalities and causes like communicable diseases put another person in danger if one person becomes ill.

- Increasing returns to scale , and , restrictions on the entry , of new healthcare suppliers create barriers to entry and inhibit competition.

- Medical professionals regularly engage in price discrimination, charging customers different prices based on their ability to pay.

All of these factors make the market for health care an absolute mess compared to most markets, which is why the industry tends to be so heavily regulated, and is probably why so many rich countries just go ahead and nationalize their health insurance systems.

Anyway, here are four examples of the fundamental economic ideas that are prevalent ( mostly ) everywhere. PhD students in modern econ departments will be assigned. Reading papers like these is how economists “historicize their methods of knowledge production,” according to Moskowitz, meaning they produced both ideas and methods that are still relevant to economics research today.

This is in contrast to the ideas of Karl Marx, which have mostly fallen by the wayside.

Is this because contemporary economists are neoliberal advocates of the free market who oppose government intervention in favor of the power of markets? No, of course not. Every single article I just mentioned addresses the issues with government intervention in the wake of market failures.

The papers don’t rely on Marxist concepts like the labor theory of value, alienation, exploitation, commodity fetishism, or the inevitable collapse of capitalism. There are many issues with markets that Marx never even considered, but the world of economic ideas is not governed by a one-dimensional axis between Marxism and neoliberalism.

I don’t know how much economics Alex Moskowitz has studied, but my bet is that he doesn’t actually know a great deal about the foundational economic thought of Paul Samuelson, Kenneth Arrow, or George Akerlof— or about modern econ research in general. So why does he think he is qualified to say that Marx belongs in the discipline’s foundational canon?

Part of the reason, of course, is that Moskowitz personally , likes and values , Marx’s ideas. He has conducted research on Marx’s ideas and links them to those of other leftist philosophers, and he also teaches classes on Marx‘s ideas. It’s natural that Moskowitz would want economists to study a thinker he likes.

I like Ursula K LeGuin, so I might suggest to English professors to view her as one of their founding intellectuals. In fact, my suggestion might be justified, and some English profs , do  , teach LeGuin.

However, my suggestion would be that of an amateur outsider because I haven’t done an English PhD or existed inside of humanities academia. ( And I would probably make the suggestion with a little more playfulness and a little less aggression than Moskowitz uses in his comments about economics. )

Because Marx wrote in a literary, discursive, non-mathematical style that Moskowitz, a humanities scholar, is able to understand ( or at least, more easily persuade himself that he understands ), Moskowitz might ask that economists include him in their canon.

Samuelson, Arrow, and Akerlof expressed many of their ideas in the language of mathematics, which Moskowitz, given , his educational background, probably doesn’t understand very well. A natural response to something is to prioritize research until you are prepared to comprehend it over something that is opaque to you, but it’s also a form of , the streetlight problem.

So I think the salient question here isn’t” Should Marx be part of the foundational economics canon”?, but rather,” Why should an English professor feel qualified to decide who should be part of the foundational economics canon”?.

And of course, politics is likely to be the answer. I don’t want to put words in Moskowitz’s mouth, of course, but he does seem like a sort of a leftist fellow:

In my opinion, non-STEM academia is seen by many leftist academicians in the humanities and social sciences as a single, cohesive enterprise, not a collection of efforts to advance knowledge in various fields, but a collective political struggle against capitalism, settler colonialism, white supremacy, and so on. In this cosmology, economists are acceptable if and only if they revere the econ-adjacent thinkers whose ideas most closely dovetail with the leftist activist struggle — e. g., Karl Marx.

And in fact, I believe that this is the most significant justification for economists to read Marx. His vision of history as a grand revolutionary struggle is a cautionary tale of what can happen when pseudo-economic thought is applied too cavalierly to political and historical questions.

Brad DeLong is an economist who has read Marx and given his writings a lot of thought. In a 2013 post,  , DeLong tried to explain , what he thought Marx got right and what he got wrong in terms of his economic thought:

Marx the economist had six important things to say, some of which are still very valuable today after more than a century and a half, and some of which are not…

Marx…was among the very first to recognize that the fever-fits of financial crisis and depression that afflict modern market economies were not a passing phase or something that could be easily cured, but rather a deep disability of the system…

Karl Marx was one of the first to realize that the industrial revolution would allow for the existence of a society where we people could be lovers of wisdom without being supported by the labor of a large number of illiterates, brutalized, half-starved, and overworked slaves…

Marx the economist got a lot about the economic history of the development of modern capitalism in England right–not everything, but he is still very much worth grappling with as an economic historian of 1500-1850. His observations that the benefits of industrialization take a long time to begin, in my opinion, are the most significant.

] But ] Marx believed that capital is not a complement to but a substitute for labor… Hence the market system simply could not deliver a good or half-good society but only a combination of obscene luxury and mass poverty. This is a question that is empirical. Marx’s belief seems to me to be simply wrong …

Marx [thought ] that people should view their jobs as ways to achieve honor or professions that they were created or as ways to help others. This leads to a very risky path for societies that attempt to abolish the cash nexus in favor of public-spirited benevolence so that they do not end up in their happy place.

Marx believed that the capitalist market economy was incapable of delivering an acceptable distribution of income for anything but the briefest of historical intervals. But “incapable” is undoubtedly too strong. [S] ocial democracy, progressive income taxes, a very large and well-established safety net, public education to a high standard, upward mobility channels, and all the panoplies of the twenty-century social-democratic mixed-economy democratic state can dissuade Marx’s notion that great inequality and great misery must be accompanied by great inequality and great poverty.

This summary, which seems eminently fair to me, establishes Marx as a peripheral, mildly interesting economic thinker — a political philosopher who dabbled in economic ideas, perceiving some big trends but getting others badly wrong, and ultimately leaving little mark on the field’s overall methodology or basic concepts. ( See Brad ‘s s slides , s video , s other commentary. )

But it’s not actually for his economic ideas that we remember Marx — it’s for his political philosophy of class warfare and revolution. And in this regard, I believe DeLong has just enough vile words to say:

Large-scale prophecy of a glorious utopian future is bound to be false…The New Jerusalem does not descend from the clouds… But Marx clearly thought at some level that it would …

Marx believed that social democracy would inevitably collapse before an ideologically-based right-wing assault, that income inequality would rise, and that the system would eventually collapse or be overthrown…

Add to these the fact that Marx’s idea of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” was clearly not the brightest light on humanity’s tree of ideas, and I see very little in Marx the political activist that is worthwhile today.

Everywhere attempt has been made to implement Marx’s proletarian revolution in an epic human tragedy. Here ‘s , what I wrote for Bloomberg , back in 2018:

It’s difficult to forget the tens of millions of people who were starved to death in Cambodia’s killing fields, under Mao Zedong, and the tens of millions who were purged, starved, or sent to gulags by Joseph Stalin, or the millions who were murdered there. Even if Marx himself never advocated genocide, these stupendous atrocities and catastrophic economic blunders were all done in the name of Marxism…20th-century communism always seem to result in either crimes against humanity, grinding poverty or both. Venezuela, the most dramatic socialist experiment of the twenty-first century, is currently experiencing complete economic collapse.

This dramatic record of failure should make us wonder whether there was something inherently and terribly wrong with the German thinker’s core ideas. Marxists will claim that Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot were merely perverted caricatures of Marxism and that the real thing hasn’t been tried.

Others will cite Western interference or oil price fluctuations…Some will even cite China’s recent growth as a communist success story, conveniently ignoring the fact that the country only recovered from Mao after substantial economic reforms and a huge burst of private-sector activity.

All of these justifications sound hollow. There must be inherent flaws in the ideas that continue to lead countries like Venezuela over economic cliffs…The brutality and insanity of communist leaders might have been a historical fluke, but it also could have been rooted in]Marx’s ] preference for revolution over evolution…]O ] verthrowing the system has usually been a disaster.

Successful revolutions typically follow the American Revolution, which preserves largely intact local institutions. Violent social upheavals like the Russian Revolution or the Chinese Civil War have, more often than not, led both to ongoing social divisions and bitterness, and to the rise of opportunistic, megalomaniac leaders like Stalin and Mao.

The successful” socialism” that people cite, the modern-day Scandinavian societies, are actually social democracies, as I pointed out in that post. They achieved their , mixed economies , through a slow evolutionary process that was absolutely nothing like the revolutionary upheavals predicted and advocated by Marx.

Economists should read Marx, and they should read him with all of this history in mind. It’s a vivid reminder of how social science ideas, applied sweepingly and with maximal hubris to real-world politics and institutions, have the potential to do incredible harm. The biggest instance of social science malpractice that the human race has ever seen is probably Marxism.

This should serve as a warning to economists — a reminder of why although narrow theories about auctions or randomized controlled trials of anti-poverty policies might , seem like small potatoes, they’re not going to end with , the skulls of thousands of children smashed against trees.

Modern economics, with all of its mathematical formulae and statistical regressions, is a model for academic study, appropriately tamed, and anchored in the quotidian search for truth, hampered by guardrails of methodological humility.

The kind of academia that Alex Moskowitz represents, where the study of Great Books flowers almost instantly into sweeping historical theories and calls for revolution and war, embodies the true legacy of Marx— something still fanged and wild.

Notes

1. As it happens, I , have  , read Marx ‘s ,” Das Kapital”. I wasn’t really thinking about it in terms of its relationship to contemporary economic theory, so it happened when I was an undergrad physics major. Also, like most German philosophy of the time, I found it both pointlessly dense and frustratingly vague.

This article was originally published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack, and is republished with kind permission. Become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.