Cambodian PM falsely claims MFP would expel migrants

Cambodian leader stirs anxiety among countrymen ahead of election in which he is almost unopposed

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has falsely claimed that the election-winning Move Forward Party plans to expel Cambodian workers from Thailand.

The veteran strongman made the claim at a rally attended by 17,000 workers from an industrial park in Kandal province on Saturday, the Khmer Times reported.

He said any plan by Thailand to expel foreign migrant workers especially those from Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar — may have a dramatic impact not only on the three countries’ economy, but also on the Thai economy which relies heavily on foreign labour.

Hun Sen himself will also face the voters in national polls on July 23, albeit without any meaningful challengers since the Supreme Court dissolved the country’s only remaining major opposition party.

“Under the caretaker government, led by Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, millions of illegal foreign workers have been granted legal status, but if they are expelled, there will be impact on the Thai economy,” Hun Sen said.

It is not clear how Hun Sen reached the conclusion that migrant workers were in danger of being forced to leave Thailand. However, one Thai administrative provision related to migrant workers was recently extended to ensure policy continuity during the period between the election and the formation of a new government.

None of the parties campaigning for the May 14 election in Thailand made any mention of policies to repatriate migrant labourers. In fact, the country’s recovering economy continues to face a labour shortage in sectors such as tourism and construction.

Successive governments have taken many steps to ensure a smoother path to legal migration and basic labour rights, working with neighbouring countries, for workers who want to come to Thailand.

Hun Sen also offered some unsolicited political advice to Move Forward, saying that the winning party should look further as “winning the election does not mean you become the Prime Minister. Up to 376 votes are needed to form a government, not just 151 votes”.

A group that helps Cambodian migrant workers in Thailand acknowledged that they were worried about their status as rumours had circulated that they would no longer be able to work in the country.

A small group of Thai people biased towards Cambodian workers have been spreading fake news, indicating that they have to return home immediately as Cambodian workers are no longer wanted in Thailand, said Ry Chay, first vice-president of The Charity Association of Cambodia.

“They distort the official information around, saying Thai authorities don’t need Cambodian and Laotian migrant workers anymore and spread it out across the country,” he told the Khmer Times.

“I get so many calls every day from Cambodian workers in Thailand who are concerned about the news, as they still want to work in Thailand. I explained to them by phone and on my Facebook page and now 60% of them have understood the information from Thai authorities.”

He said some confusion had arisen after Thai authorities informed employers that they no longer needed to register their quota of workers at the Department of Labour in Bangkok. They can now do it at the department offices in the province where their business is located.

“The Thai authorities now allow employers who need Cambodian and Laotian migrant workers to apply in their respective province, which is easier for them,” Ry Chay said.

The cabinet last week approved an extension to employment contracts that allows more than 200,000 migrant workers to keep their jobs.

The contract extension, under the terms of a broader memorandum of understanding that regulates migrant labour, will last only as long as the current government remains in its caretaker capacity.

The measure is subject to review once a new administration is formed.

According to Deputy Prime Minister Wissanu Krea-ngam, without the extension the migrant workers would have had to return home and wait until a new government took power before they could come back to resume their employment in Thailand.

A new lens on Southeast Asian street photography

If there’s one region in the world that has a lot of photographers, said publisher Suridh “Shaz” Das-Hassan, it’s Southeast Asia. With that, it’s no wonder that his latest venture is a photo journal of street photography from the region.

Though London-born and raised, Das-Hassan lived in Southeast Asia for 12 years, bouncing between Cambodia, Thailand and Indonesia. He eventually landed back in London where, along with two partners, Das-Hassan began a publishing house called Soi Books.

In Thai, the word soi means “side-street”. So it’s fitting that Soi Book’s most recent project is an upcoming, biannual journal named Plaza that will feature street photography spotlighting the everyday lives of people living throughout Southeast Asia. The arthouse-style images are in black-and-white, many with a high-grain, gritty style. The resulting frames are saturated with character, taking the focus from any individual person to a reflection of a familiar archetype, a memory or the shape of a feeling from a long time ago.

Coming from a background in film and documentary-making, Das-Hassan knows the power images hold. And with a life spent between the U.K. and Southeast Asia, he knows the talent that comes from this region and what its artists can capture through the medium of photography.

“I did a lot of migration documentaries, corruption films,” he said, reflecting on his own time in Southeast Asia. “It’s natural to marry those issues and these things, trying to see them through the prism of art, trying to basically talk about quite sensitive issues through the prism of art.”

From that, Das-Hassan believed a street-level approach to documenting life in the region was the way to go. Plaza features photographs of locals, taken by locals themselves.

“It’s very important to give an idea of Southeast Asia through the prism of people from Southeast Asia,” he said.

Ahead of the publication of Plaza’s first-ever issue, Southeast Asia Globe caught up with Das-Hassan to speak about the process behind starting the journal, Soi Books, and the publishing industry in Southeast Asia.

What is Plaza?

It’s a black-and-white Southeast Asian street photography journal. I think in a few releases, we might start changing it up and diversifying until its particular areas may concentrate on certain things. So it will probably end up being a series.

Why make a journal of photography from Southeast Asia?

I’m half-Indonesian and I was based in Southeast Asia for 12 years. I feel as a creative, and an artist, and a photographer, that the consistency of releases is what I always feel the region kind of needs.

Where will Plaza be published from?

There’s three of us: myself in London, Ryo [Sanada], who is half-Japanese and based in Brussels, and Steve [Aston], who is based in Jakarta. We’ve worked together for many years. That way, we can cover the territories, the operations, and try to get our books to retailers specifically in Southeast Asia. It’s not the easiest getting books into shops there, as you can imagine.

I suppose we’re a remote publishing company and we have printers we work with everywhere, in China, Turkey, in the U.K. We have distribution places around the world.

How did Soi Books come together?

We all had a stint in advertising in Southeast Asia to some degree. Ryo and I ran a gallery in Bangkok for about a year. Then we opened a creative agency in Singapore for a few years. Steve worked in advertising in Singapore and then Indonesia for a long time.

The circle is quite small as an expat in Southeast Asia, you start to know, like, “Oh, these are the people in Bangkok, these are the people in Phnom Penh, in Jakarta”. We always wanted to work together as a trio and come back post-pandemic, not really wanting to work in brand-land.

We wanted to go back to something a little bit more like art and a little bit more dynamic. Now we get to do our books, illustration books, potentially kids’ books down the line. We also get to do more political stuff and more social stuff, that’s something that we’re looking at.

Why did you start the street photography initiative now?

We were always documentary filmmakers, but we fell into publishing as authors many years ago. We did books on graffiti in Asia.

We’ve done a lot of books for a lot of different publishers. And then over the years of running our own studio, running our own business and then with Covid-19, it got tiring. We were just like, actually let’s just start our own publishing company. That basically means you can do the subjects that you want to do.

We can basically build our own list of titles you want to release. Because if you’re a major publisher that doesn’t necessarily want to invest in a compilation of photographers from Southeast Asia, then we can because we know there’s a number good for it. We know people dig it and we’re not gonna do huge numbers, but we’ll do a solid amount of numbers.

Speaking of, how did you go about finding the photographers for Plaza?

It is literally just research. We’re lucky enough to be working in the region a lot. I do have a lot of creatives, meaning street artists, illustrators, graffiti writers, photographers, people working in development literally around the region from China down to Papua. So it’s not too difficult to just hammer people on Instagram or email them.

If there’s one region in the world that’s got a lot of photographers in Southeast Asia. So it’s actually more of a case of discerning who’s relevant and not. It’s very important to actually give an idea of Southeast Asia through the prism of people from Southeast Asia.

Obviously, there’s a few expats but the lion’s share of it is essentially very hyper-local people.

Are there any specific photographers that stand out to you? Why?

There’s a guy called Edmond Leong in Malaysia. I think he’s fantastic, he’s like 19 or 20, a fantastic young photographer. I got that energy of wanting to do work, got a whole community of photographers around. I think he’s done some wonderful work.

There is a girl in Indonesia, in Sulawesi, Aziziah [Diah]. She does some great work, just really honest, real work. It kind of touches into development. She’s done a lot of the land grab stuff in Sulawesi, which you probably know about from Phnom Penh. She stands out.

Yeah, there are so many good and talented photographers. We’re just trying to get a good cross-section. There’s a Thai girl called Pokchat Worasub and she’s very much an artist like a super, super artist.

So, it was just trying to marry the world of super high art and maybe reportage to some degree, and try to create a platform where both can exist in the same place.

Are there any specific themes that have come up in the photographs?

The first issue is very much an overview of Southeast Asia. You know, you’ve got urban life – just a little bit of how people live, essentially. It’s street photography from the lens of photographers who live there.

Things that will come up again, urban life, housing, etc., these things are there in the visuals for you to take out yourself. We’re not putting heavy amounts of text in here. I feel that the book should exist in the world of photography, if that makes sense.

How else do you think this space has changed in the past couple of years or maybe since Covid, or even further back? Has it always been difficult to publish or is that a new thing?

I think actually it’s changed a lot. There is an element of things that feel slightly more conservative these days than really they were 10, 15 years ago, but there were good, great shops that just don’t really exist around the region.

You’ve got social media, you’ve got TikTok, so many dynamic ways of engaging the audience. It’s not just emailing the shop and they’re gonna buy some stuff. And that’s super, super, super frustrating.

I think in some respects you have to hardcore engage with social media in Southeast Asia, but then it doesn’t always translate to more cerebral stuff, if that makes sense. It’s quite hard to translate a compelling picture. I mean, it works with the photographer, but not so much in a sales kind of way, or a marketing way, for a title.

Do you think it will change?

I think it will change. I do think because of socials and more people doing interesting stuff, it will change. But who knows when and how.

In short, I think it was easier, and it’s a lot more difficult now.

Will the next issue have the same photographers, or will it be a whole new round? What about the subsequent ones after that, are they all going to be different every time?

What might happen is that a key bunch kind of stay with us, that we work with here and there. We already have some interesting people who aren’t in this one lined up for the next one. You want to basically hit 70% new people or 30% of people who worked in the last one, I think just to keep it fresh. I do think what we might do is like start going for a specific theme on the next one.

The first one is just basically a good solid street photography kind of vibe. I think the next one, we might push for something more stylised. Just push the bow out even more in terms of our layout and start seeing what works for the audience and getting feedback until we hit what we think Plaza is and that’s it.

The first issue of Plaza should be out in July, with availability by the end of the year in parts of Southeast Asia plus the U.S. and Europe, and can be purchased through the Soi Books website.

Over 100 dead bodies remain unclaimed after Indian rail disaster

BALASORE, India: Indian authorities made fervent appeals to families on Tuesday (Jun 6) to help identify over 100 unclaimed bodies kept in hospitals and mortuaries after 275 people were killed in the country’s deadliest rail crash in over two decades. The disaster struck on Friday, when a passenger train hitContinue Reading

About 83 bodies remain unidentified four days after Indian rail crash

The trains had passengers from several states and officials from seven states were in Balasore to help people claim the bodies and take the dead home, the police official added. MISSING BODIES However, all the help proved inadequate for some families. Niranjan Patra was shocked when authorities informed him thatContinue Reading

China, Russia launch joint air patrol, alarms South Korea

The joint aerial patrols, which began before Russia sent its troops in Ukraine and Beijing and Moscow declared their “no-limits” partnership, are a result of long-expanding bilateral ties built partly on a mutual sense of threat from the United States and other military alliances. In the May 2022 patrols, ChineseContinue Reading

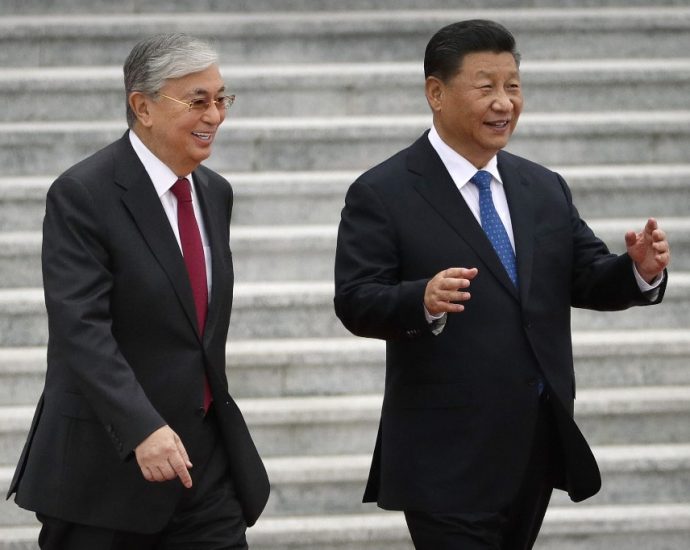

China-Central Asia: responsible statecraft according to planÂ

Francesco Sisci, a Sinologist and senior researcher at the Center for European Studies at Renmin University of China, is a highly accomplished China hand and award-winning academic who has contributed much to our understanding of economic trends and political thinking in China and across Eurasia over the past years.

As a regular contributor to Asia Times, Sisci has written scores of articles that were remarkable for their prescience and insight.

He went well beyond the conventional wisdom of the time when he wrote, in 2016, that “the rise of Asia, after the rise of China, is the future of the [European] story. Europe, with or without the EU, is more and more a part of the larger Eurasian continent that is emerging with China, which in turn has kindled the growth of the rest of Asia and is powered by new, fast, and cheap communications and transportation.”

His gift for such smart and pithy formulations helps account for why so many people follow his writing.

Which is why this writer was disappointed by his essay published on May 22 in Asia Times titled “Russia’s Zugzwang and Gorbachev vindicated”; it contains some gross inaccuracies about Central Asia’s relationship with China, and vice versa.

Sisci writes: “Last week’s summit of the five ex-Soviet Central Asian republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan) in Xian, China, indicates that China wants to step into the [Central Asian] region sensing that Russia is losing its grip there.”

One is left with the impression that China up until last month had been asleep at the switch and only recently roused itself to exploit the presumed vacuum in Central Asia occasioned by Russia’s distraction elsewhere. Such a view is puzzling, because China’s diplomatic and economic engagement with the Central Asia Republics has been deep and sustained for the past 30 years.

Sisci also seems oddly unaware that Sino-Russian relations have only deepened since the 2001 Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation Between China and Russia.

Reporting on the China-Central Asia Summit held on May 18-19 in Xian, Silk Road Briefing noted: “The Central Asian and Chinese governments approved US$3.72 billion in regional grants, signed 54 major multilateral agreements, created 19 new regional platforms and signed a further nine multilateral cooperation documents.”

These agreements did not materialize overnight.

China announced its strategic Belt and Road Imitative to the world in Astana, Kazakhstan, in 2013. Since then, transport corridors and logistics hubs have proliferated across Eurasia.

What’s more, oil and gas have been flowing eastward from the shores of the Caspian for more than two decades, and, as Aljazeera reports, “two-way trade between China and Central Asia hit a record $70 billion last year, with Kazakhstan leading with $31 billion.”

Sisci understates the case rather severely when he says China “wants to step into the region” as if it were virgin territory. In fact, the China-Central Asia Summit capitalized on and enshrined years of economic cooperation and level-headed diplomacy.

Multilateral platforms

Sisci fails to grasp the multilateral nature of the China-Central Asia Summit, that is, its prevalent ethos of “all for one and one for all,” which the participating states see as a complement to bilateral relations, not as their poor cousin.

The regional heads of state – Presidents Xi Jinping of China, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev of Kazakhstan) Sadyr Japarov of Kyrgyzstan, Emomali Rahmon of Tajikistan, Serdar Berdimuhamedov of Turkmenistan and Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan) – would not have agreed to meet in Xian on a whim, or without having prepared for the event well in advance.

They saw it was the culmination of a long diplomatic process aimed at long-term regional peace and prosperity.

Years of preparation and a shared future

With that in mind, the Xian Declaration of the China-Central Asia Summit asserted: “The parties are unanimous that the development of fruitful multifaceted cooperation between the states of Central Asia and China meets the fundamental interests of all countries and their peoples.

“Against the backdrop of changes unprecedented in a century, the parties, based on favorable prospects for the peoples of the region, reaffirm their desire to jointly create a closer community of a common destiny for Central Asia and China.”

To underscore the fruitfulness of the Xian Summit, for example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan announced that “President Tokayev returned with some 47 business and investment-related deals totaling some US$22 billion with Chinese enterprises and investors.” Kazakhstan hailed the Central Asian Summit and Tokayev’s state visit to China as constituting a “new level of cooperation between the two countries.”

Similarly, Turkmen President Berdimuhamedov, making his third trip to China in 18 months, underscored that “Turkmenistan attaches great importance to and is willing to further strengthen its Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with China.” China and Turkmenistan had been working together long before the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian war.

Kyrgyz President Japarov noted that “Kyrgyz-Chinese relations are at the highest level today.” Tajik President Rahmon also expressed satisfaction with the state of Sino-Tajik relations. In short, China has been deeply engaged in Central Asia for a long time.

January 2022 unrest in Kazakhstan

Commenting on President Xi’s keynote address, Sisci says: “It is unclear if India, Russia, Iran, or just the United States should be considered [as forces of] ‘external interference’ [in Central Asia].” Be that as it may, he then goes on to assert that “In January 2022, shortly before the Ukrainian invasion, Russia supported a coup in Kazakhstan [my emphasis], and some Kazakh leaders ran to Beijing for help.”

The historical record is clear. Kazakhstan, with the assistance of the members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, a Russian-led military alliance that includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, put down an attempted coup in January 2022 against Tokayev’s duly elected government.

It was the CSTO that supported the Kazakh government against the attempted coup – not a coup backed by the CSTO against the Kazakh government.

As for some Kazakh leaders running off to Beijing, it is not clear precisely what Sisci means by this. Suffice to say that President Xi stressed on January 10, 2022, in a personal message to President Tokayev, that “China firmly opposes any forces undermining Kazakhstan’s stability, threatening Kazakhstan’s security, and damaging the peaceful life of the Kazakh people.”

As Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev said at the Xian Summit: “Today, Central Asia is different – it is united and strong, open to dialogue and full-scale partnership.”

Bilateral and multilateral relationships between the countries of Central Asia and China are stronger than ever. That is good news for some, and bad news for others, but what is clear is that, as a Chinese proverb says, a meter of ice does not form in a single day.

China did not step into Central Asia to fill a power vacuum. Rather, the China-Central Asia Summit confirmed that – like it or not – Eurasian integration marches on, thanks in part to Central Asia’s responsible statecraft over the past decades.

Francesco Sisci responds: I am very grateful for the generous comments and I certainly have the monopoly of truth and righteousness, therefore I’d be very happy to be proven wrong. This is the way I learn.

Still, a couple of points. Surely, I didn’t express myself clearly in the Zugwang story. Yes, China’s strategy in Central Asia started a long time ago and gained momentum with the BRI. Yet I think it is important to see when things take a different twist, and the recent summit, it seems to me, moved in a different direction, something that by exaggeration I called replacing Russia influence in Central Asia.

It is an exaggeration at the moment but remarks a change in direction that appears to me clearly. Again, I may be wrong and I won’t belabor it, as I already tried to make my point in the article.

China is right in trying to walk a fine line with Russia, but the power vacuum is there and needs to be taken care of. Russia in January 2022 sponsored a coup in Kazakhstan; it doesn’t seem to me that now it has the same clout in the region.

I see major political defeats for Russia in the west, where the political goals of the Ukraine invasion have been shattered, and in the east where China, rightly, is moving ahead more quickly than before. We shall see in a few months if I was wrong.

China, Russia launch joint air patrol amid Asia-Pacific tensions

BEIJING: China and Russia conducted a joint air patrol on Tuesday (Jun 6) over the Sea of Japan and East China Sea for a sixth time since 2019, coinciding with an increase in military manoeuvres and drills by the United States and its allies in the Asia-Pacific. The patrol is partContinue Reading

Pita says iTV shares transferred, no bar to being PM

Pita Limjaroenrat, leader of the election-winning Move Forward Party (MFP), said on Tuesday his iTV shares were transferred to relatives’ names to ensure he could be the next prime minister, amid attempts to block him from entering government.

He was confident there was nothing to disqualify him from serving as an MP or becoming prime minister at the head of a new coalition government.

Mr Pita wrote on Facebook on Tuesday morning that the Prime Minister’s Office terminated its contract with iTV on March 7, 2007, and iTV had not been a media organisation since then.

The constitution prohibits a shareholder of a media organisation from running in a general election. Mr Pita’s 42,000 iTV shares recently led to complaints challenging his eligibility to be an MP at the 2019 general election, to approve his party’s candidates and to lead the next government.

Mr Pita wrote that after the contract’s termination, iTV’s frequency was re-allocated to the Public Broadcasting Service of Thailand (Thai PBS), and iTV did not have a frequency for any media role.

He said that from March 16, 2007 he held iTV shares on behalf of relatives in his capacity as manager of his late father’s estate.

“But now there are attempts to revive iTV as a mass media organisation, to attack me,” Mr Pita wrote.

He said that in its 2018-2019 financial statement, iTV was defined as a holding company but in two following financial statements it was defined as a TV organisation.

At the iTV shareholders’ meeting on April 26 this year, a shareholder asked if iTV was a media organisation. “Was the question politically motivated?… Was it an attempt to revive iTV as a mass media organisation?” Mr Pita asked on Facebook.

The irregularities prompted him to discuss the issue with relatives who had him holding iTV shares on their behalf, and they concluded that he should transfer the shares to relatives to prevent any issues from “attempts to revive iTV as a media organisation”, Mr Pita wrote.

“I am highly confident there is nothing to disqualify me from the election or being a candidate for prime minister,” he wrote.

He denied the share transfer had an ulterior purpose.

“From now on I will proceed with preparing the transition to the successful formation of the Move Forward government with Pita as the prime minister,” he wrote.

“No one and no power can block the consensus that fellow people expressed in the May 14 election through as many as 14 million votes,” Mr Pita wrote, referring to the support his party received through the ballot box at the general election.

Reporters waited outside Pheu Thai Party headquarters on Tuesday morning to question Mr Pita when he arrived there for a meeting with coalition allies. He avoided them, entering through the back door.

Apple unveils new Mac Studio and brings Apple silicon to Mac Pro

The new Mac Studio starts at US$2,066

The M2 Ultra Mac Pro starts at US$7,176

Apple introduced the new Mac Studio featuring M2 Max and the new M2 Ultra, and Mac Pro featuring the new M2 Ultra.

Mac Studio

Based on Apple’s tests, Mac Studio with M2 Max is up to 50% faster than the…Continue Reading

Ocean sanctuaries to shape geopolitics in S China Sea

Ahead of June 8, World Oceans Day, marine scientists and ocean stakeholders continue to sound alarms over the state of the oceans amid threats from climate change, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, rising sea levels, and habitat destruction.

The Economist World Ocean Outlook offers grim news about fish stocks, one-third of which are overexploited, while the anticipated global warming by 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels spells ecological disaster.

In response to these grave ecological challenges, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China are set to chart a new course for marine protected areas (MPAs) to support the health of the South China Sea and to shape a science-based multilateral cooperative agenda to preserve its marine resources.

The science is clear: Create a place of refuge in which marine life can thrive, providing more fish for all. It’s a practice that offers promise. In the face of dire environmental challenges, more governments are committed to protecting up to 30% of the ocean territory by 2030.

According to the World Resources Institute, this is especially important in Southeast Asia, which is home to nearly 34% of the planet’s most biologically diverse coral reefs.

The region’s global center for coral-reef fish, mollusks and crustaceans has experienced unprecedented threats. China has been at the forefront of the unsustainable exploitation of fish stocks and increasingly assertive in its destruction of marine habitats.

With 2,000 blue-water commercial trawlers and more than 100,000 fishing vessels, the evidence is compelling that Chinese fishing operations are contributing to the collapse of fisheries in the region.

Marine protected areas offer a safety net that is proving to be a non-threatening measure for claimant nations to support. With the stakes becoming so much higher in the contested South China Sea, these ocean sanctuaries integrate economic growth, instill environmental sustainability and sustain the seas.

Beijing faces reality

China knows that it is in dangerous waters since it has already hit its Ecological Conservation Red Line that now reflects Beijing’s urgency to protect marine spaces from development.

Over the past two decades, it has lost more than 73% of its mangrove cover and more than 80% of coral reefs. There’s increasing evidence from Chinese scientists that the marriage of policy and science is essential to navigate the perilous waters.

“I think ocean science cooperation is the best way to move, collecting and stimulating the common interests in the region to address the challenges of ocean science, regional climate, extreme weather and climate disaster and marine ecosystems,” Yu Weidong, an oceanographer and professor at Sun Yat-sen University’s School of Atmospheric Sciences, said in an e-mail communication on July 9, 2021.

In an era of rapid environmental shifts, and unprecedented economic development, China has joined ranks with ASEAN in undertaking the systematic rollout of marine protected areas. Within these no-development zones, conserving and restoring degraded coastal ecosystems are priorities. This stepped-up protection of its designated marine areas is visible in its more than 270 MPAs.

For Beijing to achieve its objectives of mitigating habitat degradation and reining in the overexploitation of resources, all stakeholders must be engaged. It will take international cooperative action for China to improve the effectiveness of its maritime management and ocean governance.

My publication Dispatches from the South China Sea: Navigating to Common Ground notes that China and its neighbor Vietnam engaged in collaborative marine workshops in the autumn of 2021 in response to the serious damage done to the “Global Commons.”

Chu Manh Trinh, a senior Vietnamese marine biologist and an effective advocate for marine protected areas, especially on Cu Lao Cham, an archipelago off Vietnam’s central coast, says, “The coral reefs in the Paracel and Spratly islands need to be carefully protected for the whole East Sea region,” as Vietnam refers to the South China Sea.

In conversations with me in March in the company of a film crew on the protected island, he spoke about the need for more marine scientists to hold dialogues to protect and conserve natural resources.

Meanwhile, the Marine Conservation Institute initiative for blue parks reveals that only 3.7% of the world’s oceans (2% in strict no-take zones) are protected by 11,169 implemented global MPAs. In Southeast Asia there remain many challenges in implementation of these sanctuaries because of the lack of resources to control catch size, quantity, and management capability.

According to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the top challenges for creating MPAs include poor prioritization of marine areas to protect, faulty implementation of protection measures, and unequal distribution, and loss of income for local communities due to the creation of no-take zones.

Despite these obstacles and disparities revealed in a “Paper Park Index” (PPI) completed by Veronica Relano and Daniel Pauly at the University of British Columbia, which focuses on MPAs that are legally designated but ineffective, their tool offers hope for improved conservation outcomes.

These marine protected areas not only contribute to biodiversity conservation, but also succeed in promoting peace and cooperation. This is particularly true with trans-boundary protected areas, or peace parks, which can be used to solve border disputes, secure or maintain peace during and after an armed conflict, and promote stable and cooperative relationships between neighboring states.

There are excellent models for marine science collaboration in cross-jurisdictional areas, such as the Arctic Council, where Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States promote cooperation on sustainable development.

Also, let’s not forget the Mediterranean Action Plan and the Red Sea, where competing nations have also managed to collaborate and foster sustainable practices seen in networked marine protected areas.

In a regional body of water with very complicated territorial and maritime disputes like the South China Sea, the development of a regional network of MPAs with marine peace parks as components offers the real possibility of decreasing tensions and enhancing cooperation between among claimants. Simply put, this brand of science diplomacy offers a crucible to avoid the worst while looking for the best.

From a political point of view, cooperation in MPAs in a disputed area might be accepted by relevant claimants more easily than in other issues. Unlike oil and gas exploitation and fisheries, the development of a regional network of MPAs does not require commercial extraction and exploitation.

“The practice of networking of MPAs can help protect an ecosystem along with the species that cannot be adequately protected in one country and promote cooperation between neighboring countries to address common issues,” Vu Hai Dang, a researcher at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam, wrote in his PhD dissertation at Dalhousie University in July 2013.

There are policy advances derived from cooperative marine science projects in the South China Sea. For instance, at the regional level, with the support of the Center for Humanitarian Dialogue, a first Common Fisheries Resource Analysis relating to Skipjack Tuna in the South China Sea was completed in September 2022 with the full participation of fisheries scientists from China, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam.

At the bilateral level, the Philippines and Vietnam plan to resume the Joint Oceanographic and Marine Scientific Research Expedition in the South China Sea. This action was initiated from 1994 to 2007 and helped acquire important data about the alarming decline in coral reefs and reef fish in the South China Sea.

The second phase may include additional participants such as China and ASEAN coastal states, which translates into more data for a South China Sea–based network of ecological reserves.

These projects are stellar examples of the compliance with Article 242 of the UNCLOS that obligates states and international organizations to promote international cooperation in marine scientific research for peaceful purposes.

While there remain plenty of obstacles for regional marine scientific research cooperation, the prospects for a trusted chart toward networked marine protected areas contributes to peace-building, offers a surplus of goodwill and provides fish for future generations.