Myanmar junta stealing from desperate migrant pockets

Tougher times await Myanmar migrant workers in Southeast Asia. Two recent orders issued by Myanmar’s junta State Administration Council (SAC) in September will result in higher costs of moving, living and working abroad for migrant workers and a fall in their disposable income and savings.

The first is the order that Myanmar migrant workers who migrate from September 2023 with the assistance of employment agencies will have to remit at least 25% of their salaries every month. These remittances must be sent through the official channel recognized by the SAC at an exchange rate significantly lower than the market rate.

The World Bank estimated the volume of remittances at US$1.9 billion in 2022, down from $2 billion in 2021 (the year that followed the coup) and $2.67 billion in 2020 (the year before the coup). Hundreds of millions of dollars or more are remitted informally and via unknown channels.

This forced remittance order by the SAC may not affect all Myanmar external migrant workers. It is practically impossible to force every one of about four million migrant workers to remit a quarter of their incomes through official channels.

The second order is the amendment of Union Tax Law 2023. It orders Myanmar nationals abroad to pay taxes, in the foreign currency they earn, starting from October 1, 2023. These taxes will be calculated at a flat rate of 2% on their total incomes or at up to 25% of their chargeable incomes (incomes after deducting tax exemptions and tax reliefs) — whichever is lower.

These forced taxes effectively amount to double taxation for Myanmar migrants who also pay income taxes where they work. This order will affect all Myanmar migrant workers, as every national abroad must show proof of tax payments or pay a lump-sum income tax when they renew their passports, which are only valid for five years. The same requirement has to be fulfilled by those who renew their passports in Myanmar.

The September orders will generate a substantial amount of foreign currency for the SAC. Though not explicitly stated, they have two targets. First, the military junta wants to discipline and punish external Myanmar migrants who are seen as major financial supporters of the resistance against the military regime.

Second, the SAC needs additional funds to support its war machine against the resistance. UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews, reported that the junta has imported war materials worth at least $1 billion since the coup.

Since 2021, the junta has become increasingly cash-strapped due to international economic sanctions and the mass boycott of goods and services produced by military-affiliated enterprises in Myanmar.

Prior to these two new orders, Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore were already subject to a growing set of securitized regulations issued by the SAC. These regulations included suspensions and delays in renewing and obtaining Myanmar passports and new migration documentation requirements introduced after the coup, such as the Overseas Worker Identification Card.

As a result of these new regulations and an increase in corruption after the coup, brokerage services have thrived in both within Myanmar and in Thailand and Malaysia, resulting in additional costs for Myanmar migrant workers.

The case of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand is particularly important. Thailand is home to at least 2 million Myanmar workers, not including several hundreds of thousands of workers who have entered and stayed irregularly. Only 350,000 of them are employed through the official Memorandum of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand.

Faced with forced remittances and income taxes, many Myanmar workers, who might have otherwise regularised their status in Thailand and obtained documentation from Myanmar immigration and labor authorities, may choose the irregular, undocumented pathway.

Aspiring migrants who are still in Myanmar and would also have chosen the official pathway might now consider irregular migration. The porous border between the two countries facilitates irregular migration.

Despite the unavoidable deduction from their incomes abroad, hundreds of thousands of people remain driven to emigrate from Myanmar. The situation at home seems increasingly grim, with no visible end to the unprecedented domestic political conflict and humanitarian crisis, as well as their severe impacts on the country’s economic situation and labor market.

While there is some irregular migration from Myanmar to Malaysia, it is not as big as in Thailand, and there is no irregular migration from Myanmar to Singapore. Documented workers, such as those in Singapore, cannot simply opt for the undocumented pathway like their counterparts in Thailand and Malaysia. They have already faced or will face the SAC rules and regulations.

Brokerage services will further thrive because many Myanmar migrant workers will have to seek passport, embassy and consulate brokers, resulting in higher fees. A significant portion of the incomes and savings of Myanmar migrant workers will be lost from forced remittances, income taxes and increasing brokerage fees.

Nyi Nyi Kyaw is Research Chair on Forced Displacement in Southeast Asia at the Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development, Chiang Mai University.

This article was originally published by East Asia Forum and is republished under a Creative Commons license.

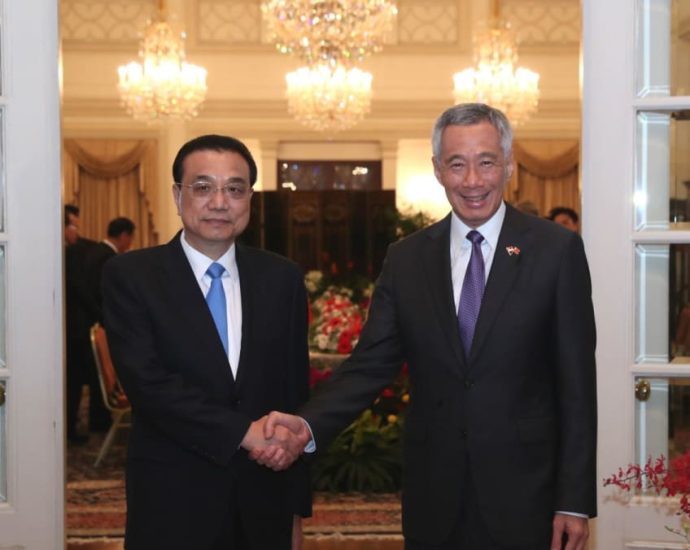

PM Lee Hsien Loong sends condolences over death of former China premier Li Keqiang

SINGAPORE: Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong on Saturday (Oct 28) expressed his condolences over the death of former Chinese premier Li Keqiang, calling him a “statesman who served his country with great dedication”.

Mr Li died of a heart attack on Friday, aged 68, about seven months after retiring from a decade in office.

“Under his leadership, China overcame many challenges, pressed on with reform and opening-up, and achieved economic development that dramatically improved the lives of the Chinese people,” Mr Lee wrote in a letter to China’s Premier Li Qiang.

He noted that he first met the former premier in 2005 in Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning province, and worked closely with him over the years to strengthen the partnership between Singapore and China.

“I warmly recall his official visit to Singapore as premier in 2018, which gave our bilateral cooperation a timely boost,” said Mr Lee.

Ten years of the Belt and Road

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which now includes 44 African countries, got under way 10 years ago. President Xi Jinping launched it in 2013 with a first speech in Kazakhstan and a second one in Indonesia. The initiative is something of a trial-by-doing development policy enigma: it keeps China watchers chasing Xi’s next move to help define just what it is.

The two speeches, however, give some lasting guidance. The Kazakhstan speech outlined five elements of the “Belt”:

- strengthening policy communication,

- road connectivity,

- currency circulation,

- people-to-people ties,

- promoting unimpeded trade.

In Indonesia, the five points were more abstract and diplomacy-oriented. They were framed as pursuing win-win cooperation, mutual assistance and affinity and remaining open and inclusive.

So, what’s happened since then? As an economist with a keen interest in the political economy of China-Africa relations, I have studied the Belt and Road Initiative since its inception.

Among the more tangible achievements so far is fostering “road connectivity.” China has helped to finance and construct highways, rail and energy projects in various countries. People, goods and commodities flow more smoothly in many places than before, within and between countries.

But at a cost. Most of these projects have been funded by loans from Chinese banks, including the China Export-Import Bank and China Development Bank.

Marking the 10th anniversary at a forum in October, Xi outlined the progress of the initiative. He also made a commitment to raise the quality of development cooperation, and provided more details on people-to-people ties and on areas of policy dialogue especially.

Much is made of a fall in spending on the Belt and Road Initiative. But if these promises take shape, the early big spending years may come to reflect a down payment. That down payment was made in times of low interest rates and kick-started some important and highly visible infrastructural projects.

Xi’s announcement at this year’s forum offered old and new news for the Belt and Road Initiative and its signatories. For African signatories (and their regional organizations and development banks) to make the most of what China is now offering, they need to understand the origins of the Belt and Road Initiative and also what has and has not changed since.

In addition, Xi’s announcement comes at a time when China’s relationship with the African continent is changing, as I outlined in a recent article.

The change sees the China-Africa relationship move beyond a focus on oil, extractive commodities and large infrastructure projects. It shifts attention to industrial production, job creation and investments that lead to African exports, and productivity-enhancing agricultural and digital technology opportunities.

This model, called the “Hunan model”, is named after the province in southern China that is leading the push. This also helps to explain why China’s lending is moving from bilateral development finance to include more commercial and trade finance lending.

Comparing promises 10 years on

Xi made eight major commitments at the October 2023 forum. More than half of these draw directly from the policy focus areas announced a decade ago.

- Xi promised to build a multidimensional Belt and Road connectivity. He referred to roads, rail, port and air transport and related logistics and trade corridors.

- He promised to open China’s economy more to the world. Higher trade levels would be one way. Alongside a new emphasis on the digital economy, Xi added that China would establish pilot zones for e-commerce-based cooperation. In Africa, a guide to those may be provided by the two existing digital commerce hubs set up by Alibaba in Ethiopia and Rwanda under its electronic World Trade Platform Initiative.

- He spoke of “practical cooperation.” This seems to refer to financing for expensive infrastructure projects, smaller livelihood projects and technical and vocational training. This has an aspect of crossover with currency circulation, people-to-people ties, unimpeded trade and more.

- Xi’s recent speech also promised to support people-to-people exchanges. This is a direct take from the first launch speech of 2013. But he added detail about establishing arts and culture alliances. Also that China would host a “Liangzhu Forum” to enhance dialogue on civilization.

- Finally, in line with the earlier commitment to elevated policy dialogue, Xi promised to strengthen institutional building for international Belt and Road Initiative cooperation. This relates to building platforms for cooperation in energy, taxation, finance, green development, disaster reduction, anti-corruption, think tanks, media, culture and other fields.

Where extending sovereign lending may present a challenge at the moment while the legacy of debt sustainability issues is addressed, Chinese policy banks are continuing to lend to institutions of the Global South.

For example, in the lead up to the forum the China Development Bank agreed on a US$400mn loan to Afreximbank to support small and medium enterprise trade efforts, with an eye on the goal of “unimpeded trade” and Africa’s own regional integration efforts under the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Beyond the promises made in Xi’s speech to this year’s forum, elevated funding for China’s policy banks was announced. Further, agreements made between participants also signal commitment to the original principles of the Belt and Road Initiative.

For example, Xi’s speech in Kazakhstan in 2013 called for elevated currency circulation. China has not only developed its mobile payments ecosystem, but is now testing its emerging central bank digital currency, the eCNY, at home and abroad.

New promises

There are three new policy promises added to those of a decade ago.

- China will promote green development, including green infrastructure, green energy, and green transportation. It will hold a Belt and Road Initiative Green Innovation Conference and establish a network of experts. China also promised to provide 100,000 training opportunities in areas of green development.

- China will continue to advance scientific and technological innovation. It will hold a conference on Science and Technology Exchange, and increase the number of joint laboratories that support exchange and training for young scientists. Xi also promised that China would propose a Global Initiative for Artificial Intelligence Governance, and promote secure artificial intelligence development.

- China will promote integrity-based cooperation. This would include publishing details of Belt and Road achievements and prospects and establishing a system of evaluating compliance.

These new areas are of increasing economic importance to China, amid rapid population aging especially, and competition with high-income countries.

The future

Where the twin launch speeches of the Belt and Road Initiative had very broad agendas, Xi’s speech at the 10-year anniversary revealed progress on earlier themes and a push to elevate the quality of development. There was more detail especially on people-to-people ties and on areas of policy dialogue to be fostered.

He added some new areas such as artificial intelligence governance, green development, e-commerce, and greater emphasis on scientific and tech cooperation. These new areas are becoming more economically important to China.

Comparing the new policy signals with the earlier ones suggests that the initiative is by design adaptable.

Further, since the Covid pandemic, some countries that had benefited from China’s new level of Belt and Road lending have run into debt problems and interest rates have risen. This signals China’s increased interest in lending to regional and locally present multilateral development and commercial banks that are relatively well-positioned to target local entrepreneurs and development.

In Africa, this offers a new chance to evolve strategies that can sustainably tap Chinese resources towards fostering the independent advance of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and local socioeconomic development.

Lauren Johnston is an associate professor at the China Studies Center, University of Sydney, and an affiliate researcher at the South African Institute of International Affairs.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

South Korea’s reserve forces need to emulate the US

Under the existing Republic of Korea-United States defense arrangement, in the event of war in the Korean theater of operations, combined component commands – air, naval, ground and marine corps – under the Korea-US Combined Forces Command play vital roles in maintaining the rock-solid combined defense posture that defends the lives of innocent citizens in Korea.

One exceptional element within such commands is the Combined Ground Component Command, led solely by the four-star ROK ground operations commander – unlike other component commands that are mostly commanded by US generals.

The CGCC, comprised of about 350,000 ROK soldiers and a couple of war-time augmented US divisions, is a striking exception to the Pershing Principle, which states that no US troops are commanded by any foreign military power and therefore it epitomizes the US commitment to defending democracy in Korea.

However, the CGCC is at a critical juncture – not due to external aggression but because of Korea’s extremely low birthrate of 0.7 per woman. In 2023, personnel who previously would have been exempted from military service – such as cancer patients and others with incurable diseases – are exponentially being assigned to active service or at least supplementary service.

At the current rate, the number of conscripts available in any given year in the 2030s is projected to be around 180,000. This falls short of what is needed to maintain a combat-ready posture, especially when considering the “3-1 rule (ratio) of land combat” against the 1.2 million North Korean active personnel.

Hence, Korea must beef up its reserve force, estimated at 2.7 million, to strive to maintain the readiness posture. This is in stark contrast to a decade ago when the number of new conscripts exceeded the established annual threshold of 300,000.

Back then, the military also adhered to an unspoken rule that reserve training should not be challenging. However, times have changed.

As part of the recent Ministry of National Defense’s (MND) re-enlistment pilot program, personnel including discharged reserve soldiers, non-commissioned officers and officers are increasingly answering the call.

While the current registered number brought in under the pilot program (only a few hundred) is not substantial, what is truly problematic is that those few reserve forces cannot completely assume active duties. They can only conduct reserve tasks, which hinders the integration of the active and reserve forces.

Moreover, due to the MND pushing for more demanding reserve training, the on-site commanders increasingly rely on symbolic incentives such as dismissing the top-performing squads early or presenting awards.

This has generated resentment among young servicemen who feel they have legally fulfilled their obligations during their active service, but are, all of a sudden, forced to do more without any tangible benefits.

Meanwhile, those who are not eager to be dismissed early have no motivation to train hard.

The rigid separation between the active and reserve components (and between peacetime and war) inhibits the overall enhancement of the ROK armed forces’ capabilities and defense readiness posture.

As in the case of the US reserve force system, facilitating re-enlistment into active positions and establishing a standing reserve force even during peacetime for integrated training of active and reserve servicemen is crucial. This approach enhances interoperability between the active and the reserve and independent mission capabilities of the reserve force in the absence of an active force – as seen in Ukraine’s war against Russia, driven by reserve forces.

The Yoon Suk Yeol administration has been gung-ho about ROK’s prospects as a “global pivotal state.” Regarding many areas of governance and statecraft, Yoon’s determination seems well-received, both domestically and internationally.

A consequence, though, is that the ROK armed forces must take on more significant roles in the region as per the raised expectations of the West. However, achieving this goal is unattainable without the ROK Army, which is not only the largest standing army in East Asia’s democratic countries but also the first responder against authoritarianism in the region, adeptly utilizing both its active and reserve forces as the situation demands.

A new reserve system must then prioritize material incentives over symbolic ones, as many younger servicemen are no longer solely motivated by patriotism and camaraderie. The aforesaid approach of assigning extra duties to young soldiers without offering tangible rewards would backfire. Implementing a legislative framework for an institutionalized reserve system, supported by monetary compensations and other benefits, is essential.

Ensuing financial challenges are a concern. However, while such apprehensions related to maintaining a standing reserve force during peacetime are valid, neglecting to enhance the capabilities of the reserve component would incur greater costs at the onset of war.

The sheer number, 2.7 million, may appear substantial, but the overwhelming majority of these 2.7 million ROK reserve servicemen primarily serve as riflemen and have limited access to the latest weaponry and advanced systems – communication, fires, administrative and so on – that the active component operates. This significant disparity in capabilities and expertise could lead to catastrophic consequences when the active force is absent.

Some might propose a mass-manufacturing of drones and robots, but once (and if) both sides’ drones face attrition, traditional infantry urban warfare would most definitely ensue. The presence of numerous cities with millions of citizens and critical infrastructure and buildings acts as a multi-layered defense north and around Seoul.

Furthermore, North Korea’s significant special warfare forces, expected to be deployed to the rear areas south of Seoul and Camp Humphreys, necessitate a bolstered reserve force to counter them. This underscores the justification for maintaining a robust reserve force to secure the rear areas.

The state of affairs in East Asia is tempestuous. The ROK armed forces have been serving as the aegis of Korean citizens. However, ROK military brass may soon have to deploy its force overseas to defend other democracies.

In such scenarios, the dwindling active force cannot be deemed sufficient. To face these evolving challenges, strengthening and utilizing the reserve is imperative.

James JB Park ([email protected] / [email protected]) is a former staffer of the South Korean Blue House and former member of the National Security Council staff, as well as a reserve captain in the ROK Army. He is currently on deferment for his MA at Columbia.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the ROK government, the presidential Blue House or the ROK military.

This article was originally published by Pacific Forum. It is republished here with permission.

Splitting the atom’s supply chain

Uranium enrichment and the nuclear fuel industry make up a globally integrated complex concentrated in the hands of a few key players. A geopolitically-driven divorce is on the horizon, however.

At the outset of the invasion of Ukraine last year, US Senator John Barrasso, a Republican of Wyoming, led an effort to ban Russian-origin uranium and nuclear products following the West’s break with the fossil fuel industries that had been filling the Kremlin’s war chest.

The bill stalled, but it highlighted America’s reliance on Russian nuclear imports and the need for a comprehensive supply chain rework. When countries are already scrambling to secure supply for nationally critical materials like rare earths or semiconductors, doing so for nuclear fuel – which powers one-fifth of US electricity generation– is not a bold proposition.

Rosatom, Russia’s sprawling state-owned champion, dominates chokepoints in the front end of the nuclear fuel cycle – 38% of global uranium conversion and 46% of enrichment. This not only gives Moscow leverage over downstream “critical infrastructure” abroad but supports its wider energy statecraft agenda.

Since 2007, nuclear reactor exports have become a key channel in Russia’s foreign influence strategy, accounting for about half of the 53 units under construction worldwide.

Additionally, leading US small-modular reactor companies like TerraPower and X-energy require high-assay, low-enriched uranium (HALEU) for their designs, and that is only commercially available from Russia.

The National Nuclear Security Administration has the ability to downblend weapons-grade material into HALEU for civil use but conflicting national security directives necessitate that it be considered a temporary solution at best.

This year, Barrasso is making more headway. The “Nuclear Fuel Security Initiative” (NFSI) breezed through the Senate as an amendment to the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act rather than as a stand-alone bill.

This would allow Congress more discretionary authority to ensure that disruptions in the nuclear fuel supply chain neither (1) impact existing commercial reactor operations, nor (2) impede the development of advanced nuclear reactors.

A companion bill banning Russian uranium (with allowances through 2027) is working its way through the House.

Opening the HALEU bottleneck is an acute priority, but the imperative should also address the broader, energy security implications of growing Russian and Chinese influence over Kazakhstan and its industry behemoth, Kazatomprom – the world’s largest uranium miner.

A disruption to the West would equate to a crisis. Nearly all producers are fully booked for years, and soaring uranium spot prices hint that warehoused sources may be depleted.

To avoid sleepwalking into a larger dilemma brought on by a captive Kazakh uranium industry, policymakers not only should empower the Department of Energy to reshore enrichment but also should firm up the broader nuclear fuel supply chain with trusted partners.

A Sino-Russo-Kazakh nuclear industrial complex?

Once known as the steady “floor” for global supply, Kazatomprom has been beset by geopolitical risks, and is on its fourth CEO in two years.

First, its primary transport route through Russia was impacted by international sanctions. Now, the bubbling Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict threatens to complicate the Trans-Caspian Route it had promoted as an alternate solution.

With access to Europe constricted and US influence in Central Asia waning, Kazakhstan has little choice but to be more accommodating towards its two assertive neighbors, who are already (by far) its most important partners in trade.

In May, Rosatom took a bite out of Kazatomprom, acquiring a 49% stake in its prized Budenovskoye-6 and -7 uranium deposits. Several executives quit as a result, fueling speculation that it was a “backdoor deal” imposed by Astana in cooperation with Moscow.

Once developed, this uranium mine complex is expected to become the world’s largest, capable of supporting Rosatom’s downstream dominance in conversion, enrichment, and fuel fabrication for many years to come.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, there were signs of Kazakhstani president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev distancing himself from Vladimir Putin, but the opposite has instead played out. The two have met in person at least a dozen times since, with energy cooperation a frequent focus.

Beijing has also factored Kazatomprom into its energy strategy. China is undergoing a massive buildout of new nuclear power plants, on track to become the world’s top producer by 2030. In his first post-Covid trip abroad, Xi Jinping visited Tokayev to lay the groundwork for deeper bilateral collaboration – with energy, again, a priority area.

Since then, the China National Nuclear Corporation has secured a major long-term uranium supply contract in excess of 50% of Kazatomprom’s total book value.

Additionally, the China General Nuclear Power Corporation has started receiving nuclear fuel assemblies from the Ulba Metallurgical Plant on the Kazakh-Chinese border – a joint venture slated to provide 200 tons of nuclear fuel each year until 2041.

Signs of deepening Russia-China cooperation over nuclear fuel may further fan this hotspot of security concerns. In March, the US House Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces was briefed on reports of Rosatom supplying highly enriched uranium to fast breeder reactors in China, a well-established pathway for weapons of mass destruction.

While there is no indication that Kazakhstan collaborates with Russia or China toward nuclear arms, evidence of an increasingly captive uranium industry presents a glaring liability for energy security in the US and Europe.

Reshoring, friend-shoring and the fuel cycle’s end

All this is coming to a head as demand for uranium is returning in force. With grids around the globe struggling to replace coal reliably with the variable generation of wind and solar, nuclear power is gaining recognition as a necessary component in the clean energy transition at large.

Nuclear plant developers from China, France, South Korea and the US are presently vying for business across Africa, Asia and the Middle East – eager to catch up with Rosatom’s lead.

And the most ominous driver of supply chain bifurcation may be the resuming buildup of nuclear weapons between great powers. China has been expanding its arsenal for years, and with Russia’s recent suspension of the “New START” arms control treaty, the US is pressured to modernize its own capabilities.

America should restore long-term nuclear fuel security before a crisis puts critical infrastructure at risk. The Nuclear Fuel Security Initiative can be maximized by (1) stockpiling uranium as disruption insurance, (2) reshoring critical bottlenecks like HALEU manufacturing and enrichment and (3) proactively friend-shoring the upstream stages of the supply chain among trusted allies.

The first two are already off the ground, with a strategic uranium reserve recently established and Ohio-based Centrus Energy beginning enrichment operations just this month.

But they require greater urgency. The reserve’s current inventory would cover only nine days of US commercial demand, and Centrus has a long way to go in scaling up to create a meaningful shift away from Rosatom.

The United States is fortunate that Canada and Australia are the number 2 and number 4 suppliers of uranium after Kazakhstan. However, the problem is that ramping up enough production to quit Kazatomprom would take many years, given the mining sector’s challenging workforce as well as lending and regulatory conditions.

Friend-shoring through policy incentives or consortium-building can accelerate this process by signaling a commitment to decoupling from the Russian nuclear industry – thereby boosting investor confidence and diverting capital otherwise flowing to marginally cheaper producers, like Namibia or Uzbekistan.

The surprising coup in Niger and its impact on France’s nuclear firm, Orano, should be lesson enough regarding dependence on states with elevated political risk for uranium supply.

Since the dual-use nature of uranium and the oligopolistic conditions of the space will never allow it to become a true commodity market, scruples over government intervention should be saved. The United States allowed Russia to maneuver into its commanding position by privatizing, then outsourcing, this critical supply chain.

Expeditiously rebuilding supply security at home and industrial capacity among allies is the first step to making a comeback in an industry that will undoubtedly remain vital within energy, technology and national security arenas for decades to come.

Brandt Kekoa Mabuni ([email protected]) is a resident WSD-Handa fellow at Pacific Forum in Honolulu.

This article was first published by Pacific Forum and is republished with permission. The article is a primer to a longer forthcoming report by the author titled “Splitting the Atom’s Supply Chain: Analysis & 3S Implications for a Disintegrating Nuclear Fuel Industry.”

US, China agree to work toward an expected Biden-Xi summit

Wang told Biden that the objective of his visit was to help “stem the decline” in US-China ties “with an eye on San Francisco”, without giving any details, according to a brief statement from the Chinese foreign ministry. The foreign ministry readouts for Wang’s meetings with Blinken and Sullivan saidContinue Reading

South Korea, US troops hold drills with drones, laser sensors

INJE, South Korea: South Korean and US troops held joint future combat drills involving drones, an unmanned vehicle and wearable laser sensors this week as part of efforts to modernise their militaries, Seoul’s army said on Saturday (Oct 27). The training came as South Korea’s military conducts a series ofContinue Reading

Fire destroys 300 shops at Surin border market

No casualties in blaze at Chong Chom market, which took 5 hours to put out

PUBLISHED : 28 Oct 2023 at 10:50

A fire raged through the Chong Chom border market in Kap Choeng district of Surin late on Friday night, destroying more than 300 shops. No casualties were reported.

More than 10 fire trucks, firefighters and rescue teams from the border district and nearby areas were deployed to combat the fire that broke out at the market in tambon Dan about 9.40pm on Friday.

The raging fire forced local residents to flee in panic. Vendors tried to take their goods and belongings at their shops to flee.

Flames spread quickly as there were many flammable materials such as clothes, beds, furniture, bags, shoes and handicraft products at the market, which housed more than 500 shops.

Local authorities said the fire started in Soi 9 at the market before spreading to other shops. Winds fuelled the fire, which took firemen until 2.50am to bring under control.

An initial survey showed about 320 shops were destroyed. The cause of the blaze was being investigated.

Firemen needed several hours to put out the fire at the cross-border market in Surin. (Photo: Surin public relations office)

More than 300 shops have been destroyed by the fire. (Photo: Surin public relations office)

A huge fire breaks out at Chong Chom border market in Kap Choeng district of Surin at 9.40pm on Friday. Many fire trucks and firemen were sent to the scene to combat the blaze, which was brought under control at 2.50am. (Photos: Surin public relations office Facebook)

Chong Chom border market devasted by fierce fire, over 300 shops burned

PUBLISHED : 28 Oct 2023 at 10:50

A fire raged firecely Chong Chom border market in Surin Kap Choeng district late on Friday night, destroying more than 300 shops. No casualties were reported.

More than 10 fire trucks, firemen and rescue teams from this border district and nearby areas were deployed to combat the fire that broke out at Chong Chom market in tambon Dan about 9.40pm on Friday.

The raging fire forced local residents to flee in panic. Vendors tried to take their goods and belongings at their shops to flee.

Flames spread quickly as there were many flammable materials such as clothes, beds, furniture, bags, shoes and handicraft products at the market, which housed more than 500 shops.

Local authorities said the fire started at soi 9 at the market before spreading to other shops. Winds fuelled the fire. Firemen put the fire under control at 2.50am. No casualties were reported.

An initial survey showed about 320 shops were destroyed. The cause of the blaze was being investigated.

Firemen take several hours to put out the fire at the cross-border market in Surin. (Photo: Surin public relations office)

More than 300 shops are destroyed by the fire. (Photo: Surin public relations office)

A huge fire breaks out at Chong Chom border market in Kap Choeng district, Surin at 9.40pm on Friday. Many fire trucks and firemen were sent to the scene to combat the fire, which was put under control at 2.50am. (Photos: Surin public relations office Facebook)

Gaza war fallout reaches Europe

With one global war still at a stalemate, a new conflict has erupted in the Middle East.

Viewed from Europe, the Israel-Hamas war is a complete minefield. It has exposed vast divisions: among European countries, between political leaders and their publics, and, most of all, between the West and the Global South, to which the West was looking for support over the Ukraine war.

A long war in Gaza threatens to harden these divisions, perhaps even to the point where Western support for Ukraine is affected.

Those divisions were on display this week, when foreign ministers from the European Union met to try to forge an agreement on the Gaza war. The EU has been internally convulsed since the conflict started.

Almost immediately, the head of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, traveled to Israel, without consulting the European Council, which represents all the national governments.

A different duo from Europe then went to Egypt to represent the EU there, before von der Leyen and the president of the European Council, Charles Michel, appeared together in Washington.

Across three continents in a matter of days, there was no consensus over who was representing the European Union, let alone what they were saying.

On Thursday, the bloc’s leaders called for “humanitarian corridors and pauses” to allow aid to reach Gaza, but only after days of bickering over the form of words. They stopped short of calling it a “humanitarian ceasefire,” as had been mooted.

Those divisions extend to their publics. There appears to be a gulf between those in power and those who vote for them. Europe has seen mass public demonstrations against the Gaza war, the largest outpouring of anti-government protests since the Iraq war.

In London, Paris, Berlin, Madrid, Athens and many other cities, tens of thousands have taken to the streets on multiple occasions, criticizing their governments’ support for the war.

Particularly in France and Germany, authorities have appeared surprised by the scale of the protests and unsure how to respond. French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin made a surprising decision to ban pro-Palestinian protests across the whole country, only to be overturned by the highest administrative court.

This week, protests took place in cities across France. Germany has also tried to use legal means to stifle demonstrations, denying requests for protests.

Such protests have had a political impact, with leaders ameliorating the language they use over the conflict, especially toward the Palestinians. But as the war drags on – the expected main ground invasion hasn’t even begun – that balancing act will become harder to maintain.

Inconsistent support for international law

An even bigger division looms with the Global South.

Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, the West has tried to rally support among non-Western countries by framing the invasion as more than a European war.

The Ukraine conflict, they argued, was about international law, and thus capitals far from the conflict – in Beijing, in Abuja, in Cairo – ought to side with Ukraine because it was about upholding the rule of law.

Then came Israel’s response to the Hamas attack. Within days, the United Nations human-rights office was warning that the siege of Gaza and the demand that a million Gazans in the north flee their homes could breach international law. More such warnings followed.

That disconnect between why the Global South was being asked to weather extreme pain over the Ukraine conflict and the extent of public support that European and North American leaders were willing to offer Israel, regardless of its military policy, was noted.

Last week, Russia brought a resolution before the UN Security Council that called for a pause in the fighting, as well as condemning the Hamas attack. Despite major Global South countries – China, Brazil – backing the resolution, and even France, the United States vetoed it.

The danger for Western countries is that this way of acting falls completely in line with what Russia and China have been arguing: that the global order only favors a handful of countries, and the Global South is not in that club. King Abdullah of Jordan put it most starkly: “International law loses all value if it is implemented selectively.”

Indeed, the aspiring leader of the Global South, China, was gifted an opportunity to demonstrate this last week, when a summit marking 10 years of the Belt and Road Initiative was held in Beijing.

Against the background of America’s frantic diplomacy in the Middle East, Xi Jinping presided over a conference with 130 countries represented, including some of the biggest Global South countries, Indonesia, Ethiopia – and, at the center of it, Russia.

That moral aspect isn’t the only issue. There’s also self-interest. Another winter is coming across Europe, and already there are signs that Europe’s attempts to restrict Russian gas sales are eroding.

A week after Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán met with Vladimir Putin in Beijing, it was announced Hungary would buy more gas over the winter.

If the West can’t even hold together countries within the EU, how likely are they to keep a broader coalition, as the Ukraine war plods toward a second winter and eventually a third year?

Taken together, the differences between leaders and publics, within Western blocs and across the Global South, pose an enormous challenge for the West, as it seeks to keep both wars in the public eye.

As the Gaza war escalates, and the front lines in Ukraine freeze, that will be harder, and the shaky coalition of the past 19 months may quietly crumble.

This article was provided by Syndication Bureau, which holds copyright.

Faisal Al Yafai is currently writing a book on the Middle East and is a frequent commentator on international TV news networks. He has worked for news outlets such as The Guardian and the BBC, and reported on the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. Follow him on X @FaisalAlYafai.