China may face a dreaded âbalance sheet recessionâ

As Janet Yellen kicks China’s economic tires in Beijing this week, she may be surprised by how often the attention is veering toward neighboring Japan.

It just so happens that Yellen’s first China trip as US Treasury secretary coincides with intense debate about Asia’s biggest economy experiencing a Japan-like “balance sheet recession,” one that, if true, will be devilishly hard to reverse.

The reference here is to economist Richard Koo’s oft-cited observation about why Japan plunged into deflation and stagnation in the 1990s. Specifically, this is when economic insecurity prods a critical mass of households and companies to prioritize boosting savings and paying down debt over consuming and investing.

Unlike a formal recession, where gross domestic product (GDP) contracts, the balance sheet variety condemns an economy to underperform for several years.

It’s clear that as 2023 unfolds, “investors are concerned that China may have entered a liquidity trap or is experiencing a balance sheet recession,” says economist Carlos Casanova at Union Bancaire Privée, with the caveat that for now “these fears might be overstated.”

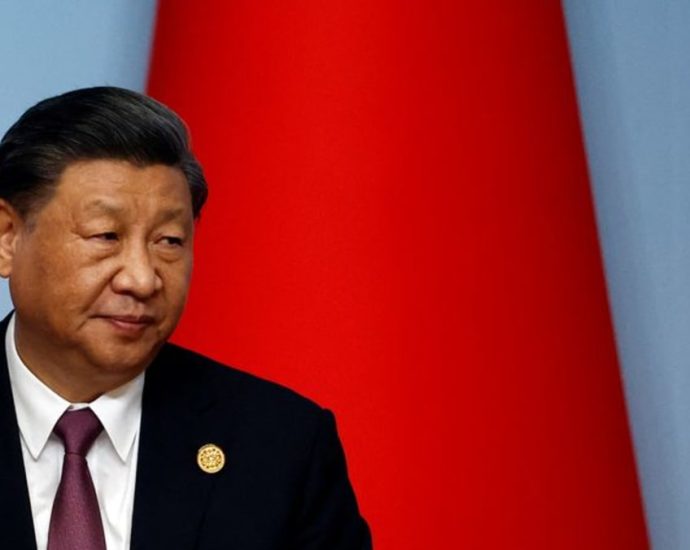

Yet the trouble with Japan-like economic funks is how souring sentiment can take on a life of its own. Herein lies the greater risk for Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang.

“Chinese policymakers are going about tackling the different factors underpinning weak sentiment,” Casanova explains. “Given the scattered nature of this support, it may take time for upside pressures on domestic asset prices to build and the Chinese yuan to stabilize.”

Koo, too, thinks China “is entering a balance-sheet recession,” partly because “people are no longer borrowing money” due to worries about the growth outlook and stability of asset markets. As households and companies focus on reducing debt, China’s growth can’t return to pre-Covid levels, he worries.

“I hope Chinese policymakers understand and respond to these challenges, because this might be the last chance for China to reach the living standards of the First World,” Koo explains.

Economist Ting Lu at Nomura Holdings worries that “China’s real estate sector is now starting to look somewhat similar to Japan in the 1990s.” As of May, for example, contract sales among the mainland’s 100 top developers were down roughly 57% versus pre-Covid-19 levels in 2019.

Though Japan’s plunge into deflation had several causes, cratering land prices — and the high degree of exposure to those prices among the nation’s biggest banks — was a key catalyst. The overhang set in motion the bad loan crisis that was core to Japan’s multi-decade malaise.

Economist Alicia Garcia Herrero at Natixis says land sales are “one of the most important components of China’s local government revenue.” She adds that “given the challenges faced by China’s property market are largely structural, i.e., slower income growth, population aging, we expect the land sales revenue to continue being under stress down the road.”

Xi’s policymakers have sought to downplay such concerns. In March, Chinese Finance Minister Liu Kun argued that a 2 trillion yuan (US$276 billion) drop in land sales would only result in a 300 billion yuan loss to local governments’ fiscal positions. That neat assessment may or may not add, however.

Clearly, economists can take the Japan-China comparisons too far. In 2021, economist Lan Xiaohuan published a best-selling book, “Embedded Power: Chinese Government and Economic Development”, detailing the unique dynamics of local property markets.

As Lan explains, “the real power is not ‘land as fiscal finance,’” but “using land as collateral to accelerate bank lending and other forms of credit. When ‘land as fiscal-finance’ meets the capital market and adds leverage, it becomes ‘land finance’” with Chinese characteristics.

Extreme opacity is an added problem. Along with privately-owned real estate companies, the top power brokers are state-owned entities known as Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs), which borrow to finance infrastructure, industrial parks and housing across Asia’s biggest economy.

LGFVs’ outsized revenue role is now among the “main obstacles for broad-based macro support” for an economy losing momentum, says Casanova. They’re at the core of “PBOC concerns about financial risks” along with “households remaining on the fence” about “deploying pandemic surpluses due to weak sentiment.”

However, Casanova notes, “without additional targeted measures, those two reinforce each other, resulting in a deflationary spiral and making it harder for the economic recovery to broaden its base.”

Yet Koo argues that China has a key advantage over Japan: it can learn from Tokyo’s mistakes.

The key lesson, Koo says, is that stimulus treats the symptoms of China’s troubles, not the underlying ailment. While it’s vital that Beijing steps forward to ensure that giant building projects are completed, reforms to repair the property sector and build robust social safety nets are the key to avoiding “Japanification” risks.

Stabilizing property is vital to improving the quality of economic growth and reducing the frequency of boom-bust cycles. Social safety nets are needed to prod households to save less and spend more.

The good news is that China has “a fairly strong administrative system which can put losses where they should be — where they can be easily absorbed,” Raghuram Rajan, former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, told Bloomberg.

It may help, too, that the economic reform portfolio is now in Li’s hands. Unlike his predecessor, the newish premier appears to have Xi’s full confidence. That top-level buy-in is vital if Li is to pull off a monumentally difficult balancing act.

Li must support growth in the short run while maintaining the progress China has made in reducing extreme leverage and getting under the economy’s hood to recalibrate engines from exports to domestic consumption. Naturally, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) will play a key role in smoothing out GDP.

Markets need to be “thinking about the likelihood of further easing ahead,” says economist Rob Carnell at ING Bank referring to benchmark Chinese interest rates. He adds that “we’re going to get plenty more of those” moves to add liquidity in coming months “to keep [the] yuan on the back foot.”

Economist Joey Chew at HSBC Holdings says “some think that more concrete, non-monetary stimulus measures will only come out at or after the Politburo meeting in end-July. If so, some foreign-exchange policy smoothing may be needed in the meantime as we head into the dividend outflow season for China.”

Not everyone is convinced big stimulus moves are coming. Goldman Sachs economist Maggie Wei notes that recent meetings with greater China region investors unearthed lots of doubt. “Local clients did not expect major policy easing measures or structural reform measures to be rolled out in the July Politburo meeting” later this month, Wei says.

To some extent, the yuan’s 5% drop this year limits the PBOC’s options. Indeed, additional rate cuts might weaken the yuan to levels that exacerbate trade tensions with Washington and Tokyo. At the same time, a weaker yuan would increase default risks for China’s bigger property developers.

“The lesson from Japan’s lost decades is that without a timely debt clean-up and demand stimulus, the deleveraging mindset could become entrenched in the private sector and, after a certain point, even zero interest rates would not be able to help,” says economist Wei Yao at Societe Generale. It follows that “such a danger seems increasingly relevant for China, as evident in households’ strong appetite for savings.”

In the interim, interest margins among mainland banks “will be under persistent downward pressure if more of their lending capacity is used for extending loans to LGFVs at below-market rates,” Yao says.

China also faces an imponderable that Japan didn’t in the 1990s: a full-blown trade war with Washington.

Yellen’s presence in Beijing this week speaks to the high drama complicating Li’s job in stabilizing the economy. To some observers, Yellen’s trip is meant to reduce the geopolitical temperature following US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s recent visit.

“I would say it’s a little bit like good cop, bad cop, Blinken being the bad cop,” former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff told the BBC. “And now Yellen going in as the good cop trying to say, look, you know, we have a lot in common. Let’s see what we can do together.”

Even so, Yellen manages to throw some sharp elbows. On Friday, she chided Beijing for policies toward US companies and a recent move to limit the export of gallium and germanium, niche minerals used in some chip-making.

“During meetings with my counterparts,” Yellen said, “I am communicating the concerns that I’ve heard from the US business community — including China’s use of non-market tools like expanded subsidies for its state-owned enterprises and domestic firms, as well as barriers to market access for foreign firms. I’ve been particularly troubled by punitive actions that have been taken against US firms in recent months.”

Xi’s government, of course, has its own gripes about US President Joe Biden’s efforts to make American manufacturers less reliant on Chinese production.

In the meantime, though, it’s hard to refute that “China’s economic development model resembles that of Japan over 30 years ago with high savings and high investment, but with restrained consumption and rigid institutions weighing increasingly on macroeconomic success,” notes George Magnus, a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre.

Magnus adds that “China’s chronic over-investment and misallocation of capital, particularly in the property sector, pose a potentially bigger economic problem than Japan’s banking crisis in the 1990s.”

On the bright side, Magnus says, “China has some advantages over Japan, such as a state-owned financial system that can prevent significant banks from failing and a closed capital account that can protect the country’s banking system and the economy from the risk of significant capital flight. This however might not prevent China from taking the same economic trajectory [of] Japan.”

That requires urgent and creative moves to repair the property market, create robust social safety nets and put China on a path toward more productive economic growth. China can surely avoid Japan’s lost decades, but there’s not a moment to waste in shifting the narrative about the economy’s downward trajectory.

Follow William Pesek on Twitter at @WilliamPesek

China’s Xi urges greater innovation amid tech curbs from US

BEIJING: China’s President Xi Jinping, on an inspection tour of a major industrial province, renewed his call for greater innovation and technological self-reliance, as the United States intensifies curbs on Chinese access to advanced technologies. China should accelerate the upgrades of key technologies and core products, state-run Xinhua news agencyContinue Reading

22m meth pills, 620kg ice seized; 17 arrested

The Narcotic Suppression Bureau (NSB) seized 22 million methamphetamine pills and 620 kilogrammes of crystal methamphetamine, or ice, and arrested 17 suspects in seven cases between June 12 and July 5, the deputy national police chief said on Friday.

The NSB also impounded 12 vehicles and assets worth 8 million baht, suspected to be acquired through the drug trade, for further investigation, Pol Gen Chinapat Sarasin said in a press conference.

The seven cases were as follows:

• On June 12, acting on a tip-off that a large quantity of drugs would be delivered from Tha Uthen district in Nakhon Phanom province, a police team followed a Chevrolet pickup truck from an intersection in Sakon Nakhon province to a house in Muang district, Khon Kaen province. A subsequent raid led to the discovery of 2 million meth pills in the vehicle, and the driver was arrested. An investigation is ongoing to identify other members of the network.

• On June 13, two suspects were arrested after police searched a pickup at Wat Khok Krataithong in tambon Champa of Tha Rua district, Ayutthaya province. The officers found 500kg of crystal meth.

Further investigation led to the arrest of two additional suspects at a market in tambon Kut Nok Plao in Saraburi’s Muang district. Both suspects admitted that they had acted as an advance team on the lookout.

The drug belonged to a drug network of a Hmong ethnic group in the North.

• On June 19, a car was stopped in front of a company on Highway 201 in Muang district of Chaiyaphum. During the search, police found three sacks containing 120kg of crystal meth in the car. The driver, who had been hired to deliver the drugs from Bueng Kan province, confessed that he had done so five times previously. Investigations are underway to uncover the network.

• On June 28, police intercepted a pickup in front of a convenience store in Lop Buri province and found 3 million meth pills hidden under the front seat and in the rear of the vehicle. The driver was arrested. His accomplice, who was driving in another pickup on the lookout, was arrested at Moo 1 village in tambon Sam Phaniang in Ban Phraek district, Ayutthaya province.

• On July 1, a pickup was stopped and searched at an intersection in Muang district of Chiang Rai province, resulting in the discovery of 6 million speed pills. Two men were arrested, and it was found that the drugs had been delivered from Chiang Mai’s Mae Ai district.

• On July 3, six suspects were arrested at a petrol station in Muang district, Nakhon Ratchasima province, with three pickups. Found in the three vehicles were 5 million meth pills in 12 sacks. The suspects had delivered the drugs from an area near the Mekong River in That Phanom district, Nakhon Phanom province, heading for Bangkok. Following an investigation, the suspects’ assets worth about 8 million baht were impounded for further examination.

• On July 5, a pickup was intercepted on Mittraphap road in tambon Tanot in Non Sung district, Nakhon Ratchasima province. Fifteen sacks containing 6 million meth pills were found, and the drive was arrested. The drugs had been transported on the Mukdahan – Maha Sarakham – Nakhon Ratchasima route.

In the month of June, the NSB seized a total of 18 million meth pills, 1,983kg of ice, 46kg of heroin and 5,856 ecstasy pills in 18 cases. A total of 30 suspects were apprehended during this period.

The seized drugs are undergoing examination at designated offices and will be stored at the Public Health Ministry for destruction.

Police display illicit drugs seized from seven cases during a media briefing at the Narcotic Suppression Bureau head office on Friday. (Video: Police TV)

Fukushima water release plan clears last regulatory hurdle in Japan

By then, the radiation level “is projected … to be scientifically irrelevant”, he added. The discharged water is treated to remove almost all radioactive elements apart from tritium, which is commonly found in nuclear plant wastewater pumped into the sea. The water will be diluted with seawater before release, andContinue Reading

Thai elephant under ‘normal conditions’ in Sri Lanka

Ambassador says no plans to bring back Thai elephant from Sri Lanka

Pratu Pha, a 49-year-old male elephant, has been living under normal conditions in Sri Lanka, and Thai authorities have no plans to bring back the jumbo to Thailand, according to the Thai ambassador to this island country.

Ambassador Poj Harnpol said on Friday that he visited Pratu Pla at Wat Sri Dala Maligawa, or the Temple of the Tooth Relic, in Kandy City on Thursday. The visit was made at the invitation of Pradeep Nilanga Dela Nilame, the temple caretaker. The “ambassador elephant” is under the care of the temple.

During the visit, Mr Poj told the temple caretaker that Thai authorities would collaborate with Sri Lanka by sharing knowledge in elephant care and developing veterinary resources.

According to Mr Poj, the pachyderm lives in an open courtyard with cement and soil surfaces, marked by ropes to indicate boundaries. The elephant’s front legs are chained to two big trees, while one of the hind legs is lightly chained, allowing it to move and stand naturally.

Pratu Pha can consume food such as leaves from kithul trees, grass and sugarcane as normal, said the ambassador. During his observation period of over 30 minutes, the elephant did not display any signs of aggression, and a mahout was able to feed the animal from a distance.

Mr Poj emphasised the importance of improving the landscape and ensuring adequate water sources and water tanks for the elephant’s well-being.

“Although the general condition is satisfactory to some extent, Pratu Pha’s living conditions could still be improved,” said the Thai envoy. “We acknowledge the efforts being made by the temple, but the situation cannot be changed in a day. We will work towards better care.”

In an interview with Sri Lankan media, Mr Poj assured that Thailand has no plans to bring back Pratu Pha, also known as Thai Raja.

He said the repatriation of ailing elephant Sak Surin, or Mutha Raja, to Thailand for medical treatment had raised awareness about the rights and improved care of elephants and other animals. Thailand and Sri Lanka would focus on future cooperation, he added.

Pratu Pha was sent gifted to Sri Lanka 37 years ago, while Sak Surin and another male jumbo, Sri Narong, were sent there 22 years ago as goodwill gifts.

Earlier, there were social media reports that the Sri Lankan government would sue Thailand if it intended to bring back Pratu Pha and Sri Narong.

On Thursday, Attapol Charoenchansa, acting chief of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP), said Thailand had no policy to reclaim the “ambassador elephants” in Sri Lanka.

Thai elephant in ‘normal conditions’ in Sri Lanka

Pratu Pha, a 49-year-old male elephant, has been living under normal conditions in Sri Lanka, and Thai authorities have no plans to bring back the jumbo to Thailand, according to the Thai ambassador to this island country.

Ambassador Poj Harnpol said on Friday that he visited Pratu Pla at Wat Sri Dala Maligawa, or the Temple of the Tooth Relic, in Kandy City on Thursday. The visit was made at the invitation of Pradeep Nilanga Dela Nilame, the temple caretaker. The “ambassador elephant” is under the care of the temple.

During the visit, Mr Poj told the temple caretaker that Thai authorities would collaborate with Sri Lanka by sharing knowledge in elephant care and developing veterinary resources.

According to Mr Poj, the pachyderm lives in an open courtyard with cement and soil surfaces, marked by ropes to indicate boundaries. The elephant’s front legs are chained to two big trees, while one of the hind legs is lightly chained, allowing it to move and stand naturally.

Pratu Pha can consume food such as leaves from kithul trees, grass and sugarcane as normal, said the ambassador. During his observation period of over 30 minutes, the elephant did not display any signs of aggression, and a mahout was able to feed the animal from a distance.

Mr Poj emphasised the importance of improving the landscape and ensuring adequate water sources and water tanks for the elephant’s well-being.

“Although the general condition is satisfactory to some extent, Pratu Pha’s living conditions could still be improved,” said the Thai envoy. “We acknowledge the efforts being made by the temple, but the situation cannot be changed in a day. We will work towards better care.”

In an interview with Sri Lankan media, Mr Poj assured that Thailand has no plans to bring back Pratu Pha, also known as Thai Raja.

He said the repatriation of ailing elephant Sak Surin, or Mutha Raja, to Thailand for medical treatment had raised awareness about the rights and improved care of elephants and other animals. Thailand and Sri Lanka would focus on future cooperation, he added.

Pratu Pha was sent gifted to Sri Lanka 37 years ago, while Sak Surin and another male jumbo, Sri Narong, were sent there 22 years ago as goodwill gifts.

Earlier, there were social media reports that the Sri Lankan government would sue Thailand if it intended to bring back Pratu Pha and Sri Narong.

On Thursday, Attapol Charoenchansa, acting chief of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP), said Thailand had no policy to reclaim the “ambassador elephants” in Sri Lanka.

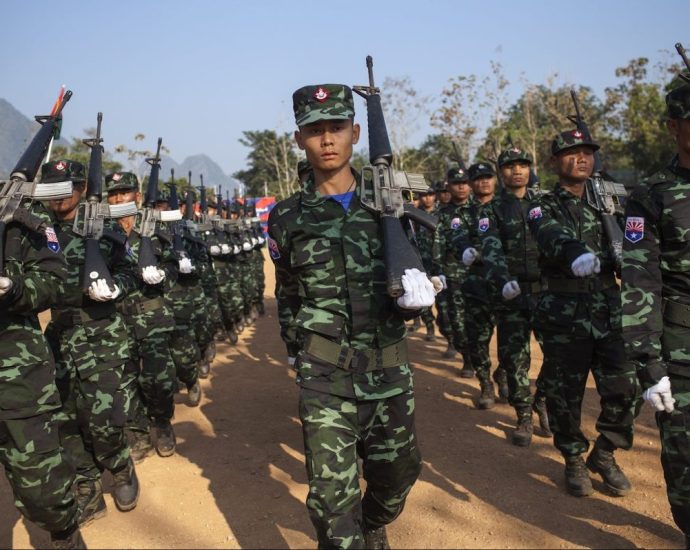

Blowing the bridge on Myanmarâs shifting civil war

At the onset of a monsoon season unlikely to see much respite in Myanmar’s raging civil war, the month of June was especially unkind to a coup regime struggling to impose its will on a nation in revolt.

The State Administration Council (SAC) junta’s woes were compounded by additional US sanctions on a listing banking sector, Chinese-brokered talks with three key ethnic armies that ended in failure and the first defections of entire military units to the anti-coup opposition, undercutting the regime’s already tenuous hold on a swathe of eastern Kayah state.

Attracting less attention amid the apparent confusion of a “war of a thousand cuts” was a string of attacks, also in the east of the country, that viewed together should have worried army headquarters in Naypyidaw rather more than the loss in Kayah of two ethnic Karenni Border Guard Forces (BGF) battalions of transparently dubious loyalty.

Underpinned by a notable new level of strategic planning and tactical execution, the opposition’s June strikes highlighted an operational approach which, as it gains traction across a multi-front war, is calculated to aggravate the central vulnerability of an army trapped between a crippling lack of manpower and overly extended areas of operations.

The attacks also belied suggestions that unchallenged regime airpower can impose a military stand-off in which a better-resourced SAC needs only to wait out ethnic and political fissures in the opposition camp.

Bridges in the crosshairs

Not by coincidence, the series of coordinated assaults through the month zeroed in on bridges.

While geographically scattered, the attacks conveyed a clear message: For the first time, joint ethnic and Bamar resistance forces have conducted operations reaching into the national heartland to target infrastructure that is essential to the resupply of an army already facing a critical shortage of transport helicopters and that cannot be defended by airpower.

Beginning at dawn on June 1, the first operation involved a wave of synchronized assaults by forces of the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA)’s 1st Brigade and allied, newly-formed People Defense Force (PDF) units on posts at both ends of the Donthami bridge.

A major span across the Donthami River near Thaton, the bridge is situated on the Asian Highway where it passes through Mon state linking Yangon to the Karen state capital of Hpa-an and the trade hub of Myawaddy on the Thai border.

The clashes reportedly continued for some 90 minutes and backed up traffic for a lot longer. While media reports of 45 army troops killed were likely inflated, the aggressive assaults probably intended to overrun the posts guarding the bridge had most certainly occurred.

Less than a week later, on June 6, a second operation in Kyaukkyi township of Bago region underscored the fact that the Donthami raid had not been a one-off.

Launched again at dawn, the action brought together a joint task force from the KNLA’s 3rd Brigade and allied PDFs and reportedly saw a police station and four army posts overrun followed by the demolition of the Bonthataw bridge across the Sittang River.

While accounts of up to 30 soldiers and police killed remain unconfirmed, drone images of the collapsed easternmost section of the bridge where the wide concrete structure meets the riverbank left no doubt that road connectivity between Kyaukgyi, east of the river and Kyauktaga on the west bank, a town on the main Yangon-Naypyidaw road and rail line, had been severed for at least the coming months.

On the same day, KNLA-led forces also reportedly blew a smaller bridge at Nat Ywar in Htantabin township, north of Kyaukgyi, not far from the transport hub of Toungoo city. That marked the second bridge destroyed in Htantabin in the space of ten days.

According to an official report carried May 30 on the state-run website myanmar.gov.mm, “PDF terrorists” had already destroyed an iron bridge on a road leading to a much larger bridge over the Sittang on May 26.

The most disruptive attack, however, was again on the main Asia Highway artery in the early hours of June 29 when sappers of the KNLA 1st Brigade and PDFs brought down a 24-foot (7.3 meter) wide section of the Kyone Eit Bridge in Mon state’s Bilin township.

Daylight images of the scene indicated that a major explosion had collapsed two-thirds of the bridge into the canal below, destruction that later took the life of an unfortunate motorist who at speed or in pre-dawn darkness drove his car into the newly-opened abyss.

Deliberately, however, the demolition squad had laid charges that left one 12-foot wide lane supported by two concrete pillars still navigable for road passage but inevitably resulting in major traffic bottlenecks.

The bridge blast was followed up by clearly well-prepared attacks by armed drones on regime officials inspecting the damage later in the morning, in which two were killed and some 27 others, mostly police and soldiers, wounded – a blitz which incidentally served to underscore the lethal advances in the resistance’s drone capabilities.

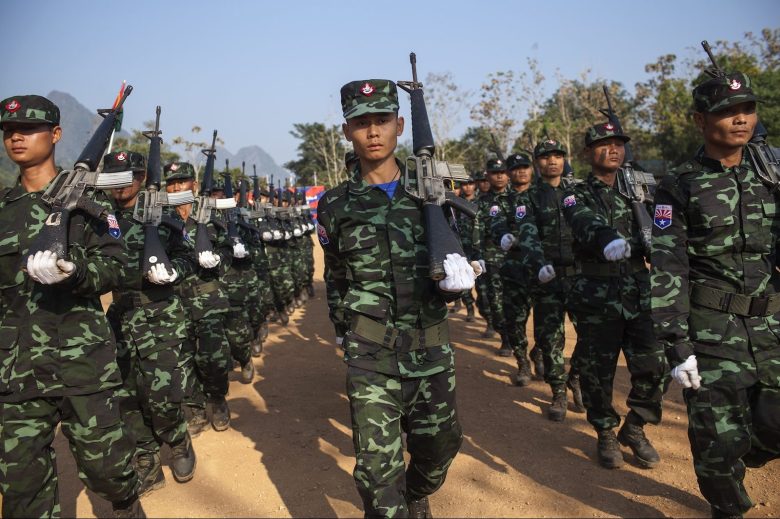

Evolving resistance

Against the backdrop of the typically chaotic, come-as-you-please attacks on regime facilities that for many PDFs in central Myanmar are still the preferred approach to war, June’s Karen-led bridge raids stood out at the tactical level as striking examples of planning and execution that the National Unity Government’s (NUG’s) Ministry of Defense would do well to disseminate as lessons-to-be-learned across resistance ranks more broadly.

As complex operations requiring effective integration of disparate elements, success hinged on careful target selection and planning; up-to-date intelligence; reaching targets in darkness but on time; and then synchronizing the roles of several teams with different tasks at different locations, including those conducting preliminary assaults on posts calculated to disperse the impact of retaliatory artillery strikes and the follow-on demolition squad equipped with military-grade explosives and the training to use them to effect.

In the case of the Sittang bridge operation of June 6, all of that needed to be followed by withdrawal in daylight amid an alert and angry enemy reacting both on the ground and from the air.

Strategically, the geography of operations, presumably loosely coordinated between the NUG’s regional commanders and relevant KNLA brigades, was no less telling.

In the Sittang valley, the sabotage of key bridges increases pressure on isolated regime positions in a corridor of territory running north-south between the resistance-dominated Karen hills in the east and the river in the west. Linking this string of small garrisons is an already vulnerable secondary road between Toungoo in the north and Shwegyin in the south.

Kyaukgyi sits halfway along the corridor, a lynchpin town that the destruction of the Bonthataw bridge has now largely cut off from resupply by road from west of the Sittang. The coming months of the rainy season are likely to see stepped-up interdiction of the road by guerrilla forces now operating along its entire length, and possibly the abandoning or fall of the isolated regime positions it connects.

As commanders on both sides of the conflict are fully aware, a few short kilometers across the river on its west bank lie the main road and rail arteries linking Yangon to the capital Naypyidaw and the central city of Mandalay.

Those national arteries, in turn, are overshadowed by the central spine of the Bago Yoma mountains where in earlier conflicts Karen and communist guerrillas established base areas and springboards for attacks.

To the south in Mon and Karen states, the strategic threat posed by the KNLA-PDF alliance is far more immediate: aggressive guerrilla operations already threaten road connectivity between major cities.

The June bridge attacks marked a significant escalation of pressure exerted earlier in the dry season by the KNLA’s Thaton-based 1st Brigade and its affiliated PDFs on highways connecting Yangon, Mawlamyine (Moulmein) and Hpa’an.

Operations in the Thaton-Bilin zone in Mon state mirror a trend seen further east along the main road to the Thai border, where the KNLA’s 6th Brigade and PDFs have been constantly active in and around the highway towns of Kyondo and Kawkareik.

The cumulative impact of this activity has been a sharp spike in army casualties and the sacking of the commanders deemed responsible.

In early April this year, Major General Myat Thet Oo, commander of the Mawlamyine-based Southeastern Regional Military Command, was relieved of his post and later consigned to see out his career as ambassador to Laos.

His boss, Lieutenant General Khun Hlaing, head of Bureau of Special Operations No 4 which oversees operations in both Karen and Mon states, was also abruptly fired.

Roadblocking the regime

At a stage of the war when the capture of urban centers by opposition forces is neither practical nor desirable, a strategy of squeezing key lines of communication connecting them is emerging by default as an optimum way forward.

As evidenced in June across the KNLA’s wide Karen-Mon-Bago area of operations, the approach requires loose operational coordination at the regional level rather than any overarching and ultimately counter-productive attempt to impose strategic coordination on ethnic armed organizations operating in different parts of the country and facing very different military and political constraints.

In some cases, the pressure of constant ambushes central to this insurgent strategy has forced the military to essentially abandon key roads where the cost in lives and vehicles has come to outweigh the value of keeping them open.

The road between Kalay, a regional operations command center in northwest Sagaing and the crossroads town of Gangaw in Magwe region to the south, offers a striking case in point.

An extended 120-kilometer-long artery skirting the Chin Hills, which from late 2021 through 2022 was the scene of weekly clashes and army reprisal attacks on villages, the road has been abandoned this year as the military pulled back to its Kalay redoubt.

Along major highways the regime cannot afford to surrender, the alternative resistance scenario involves a campaign of ongoing ambush and disruption reinforced where possible by the blowing of bridges and the hemorrhaging of army manpower such assaults inflict.

This reality has already emerged both along so-called “IED Alley”, the highway between Sagaing City and Monywa, headquarters of the military’s Northwestern Command; and in a very different shape involving larger, better-organized and better-equipped Karen and PDF forces along the Asia Highway in Mon and Karen states.

The strategy’s success can be measured as military movements become fewer and concentrated in larger convoys that require the escort of armored fighting vehicles and helicopter gunships.

The military has already been forced to resort to this expedient in western Chin state and along stretches of the Ayeyarwady River in the Sagaing-Kachin border region where gunship escorts have been deployed to protect riverine movement of supply barges headed north.

Air war folly

These trends are emerging against the backdrop of the Myanmar Air Force’s failure to achieve appreciable impact on the battlefield.

Despite record numbers of sorties flown this year, at huge cost in ordnance dropped and fuel expended, the brunt of the MAF’S air war has fallen on civilians while resistance forces operating in small units without easily identified logistics hubs have suffered seemingly minimal casualties.

Indeed, the overall impact of the MAF’s campaign has been primarily psychological: terrorizing civilians while bolstering the morale of embattled penny-packet regime outposts.

In far more lethal conflicts from World War II onwards, air assaults on civilian populations have ultimately proved counter-productive, fanning popular resolve to fight. Scrambling to support positions under mounting pressure, but ultimately too numerous all to be defended from the air, the military prong of MAF strategy represents at best a “finger in the dyke.”

In protracted conflicts that fail to provide sufficient daily drama easily measured in lives lost or kilometers gained, the international news industry is inclined to declare a “stalemate” and move on. Over the past year, Myanmar has been no exception to this tendency sometimes wrapped in the reassuring conclusion that the war is one that “neither side can win.”

How or even if Myanmar’s popular opposition can “win” remains to be decided but it would be folly to discount the remarkable mobilization, sustainability and access to armaments it has achieved in two short years – advances that, as indicated in June, continue to evolve in ways that are not immediately obvious but undoubtedly significant.

In the context of a civil war that is in many ways unprecedented, speculation into the future is of dubious value. But if current trajectories are any guide, it might focus more usefully less on who will win and more on how and when the nation’s floundering military will lose.

Robodebt: Illegal Australian welfare hunt drove people to despair

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA landmark inquiry in Australia has found an illegal welfare hunt by the previous government made victims feel like criminals and caused suicides.

Known locally as “Robodebt”, it was an automated government scheme which incorrectly demanded welfare recipients pay back benefits.

People received letters saying they were owed thousands of dollars in debt, based off an incorrect algorithm.

More than half a million Australians were affected by the policy.

The scheme ran from 2016 until it was ruled illegal by a court in 2019. It had forced some of the country’s poorest people to pay off false debts.

Many were forced into worse financial circumstances – taking out loans, selling their cars or using savings to pay off a debt they were told they had to pay within weeks. Others described being vilified and feeling shame after being told they owed money.

On Friday, a royal commission inquiry into the scandal issued its final report, describing the scheme as a “costly failure of public administration” with “extensive, devastating, and continuing” ill-effects.

“Robodebt was a crude and cruel mechanism, neither fair nor legal, and it made many people feel like criminals,” Commissioner Catherine Holmes wrote in her 990-page report.

A royal commission is Australia’s most powerful form of public inquiry. This one ran for 11 months and drew hundreds of public submissions.

On Friday, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese condemned the previous government’s scheme as a “gross betrayal” of citizens, which had harmed the most vulnerable.

The inquiry found there were at least three known suicides as a result of Robodebt policy, and it was “confident that these were not the only tragedies of the kind”.

The deaths by suicide included two young men Rhys Cauzzo, 28, and Jarrad Madgwick, 22, whose mothers gave testimony to the commission last year on their behalf. The other was not identified. Kath Madgwick had previously told the BBC she holds the government responsible for Jarrad’s suicide.

Other victims told the inquiry how the stress of a debt demand had caused them anxiety and depression and led them to consider suicide.

One woman said she felt suicidal for a period of months with the debt hanging over her head, with the “lowest point” being the day the debt collector debited the money from her bank account.

“I felt desperate on that day; it was so upsetting that I could not afford to pay for my daughter’s medical expenses and I felt powerless to improve my situation,” she told the inquiry.

Another victim, who had experienced mental illness previously, said that upon receiving a $A11,000 (£6,300, $8,100) debt notice, he was in “complete shock”, because it would “set me back years and years and years”.

He explained that “from a generalised anxiety disorder point of view, it’s just… the biggest trigger you can give to somebody.”

The inquiry’s final report on Friday criticised former Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s conservative government for launching the scheme where “little to no regard was had to the individuals and vulnerable cohorts that it would effect”.

The report also condemned Mr Morrison – who had been minister of the social services department at the time the policy was launched – for “misleading” Cabinet over advice that the switch to an automated system would not require legislative passage.

In response on Friday, Mr Morrison said he rejected “each of the findings which are critical of my involvement in authorising the scheme and are adverse to me”.

He maintained he had “acted in good faith and on clear and deliberate department advice”.

The report also accused the government of persisting with a cover-up of the scheme once its “unfairness, probable illegality and cruelty became apparent”.

“It should then have been abandoned or revised drastically, and an enormous amount of hardship and misery… would have been averted,” it said.

“Instead the path taken was to double down, to go on the attack in the media against those who complained and to maintain the falsehood that in fact the system had not changed at all.”

Commissioner Holmes also described a politicisation of welfare policy that had exacerbated a stigma often felt by recipients of social welfare.

The government also falsely exaggerated incidents of welfare fraud which were “miniscule” or less than 0.1% of cases, the report found.

The Morrison government abruptly ended the Robodebt scheme in 2019 after victims contested the legal basis in the Federal Court of Australia, where it was found to be illegal.

In its backdown, the government was also forced to refund over A$700m of payments to victims. It also settled a billion-dollar lawsuit brought by victims seeking compensation.

If you are feeling emotionally distressed and would like details of organisations in the UK which offer advice and support, go to bbc.co.uk/actionline.

If you are in Australia, you can call Lifeline at 131114, Kids Helpline at 1800 55 18000 or visit the Beyond Blue website.

Related Topics

-

-

18 November 2020

-

Philippines writes off US$1 billion in farmer debt to boost food production

MANILA: Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos on Friday (Jul 7) wrote off US$1.04 billion in land-related debt owed by more than half a million farmers, a move aimed at boosting food production. The “New Agrarian Emancipation Act” he signed into law waived all property-related debt owed by farmers who had beenContinue Reading

China’s Alibaba and Huawei add products to AI frenzy

Chinese tech companies are aggressively developing AI products after the ChatGPT chatbot by OpenAI ignited a generative AI boom. McKinsey estimates that generative AI could eventually add US$7.3 trillion in value to the world economy each year. Alibaba’s image generator will compete with OpenAI’s DALL-E and Midjourney Inc’s Midjourney, US-basedContinue Reading