Chinaâs default drama cries out for faster reforms

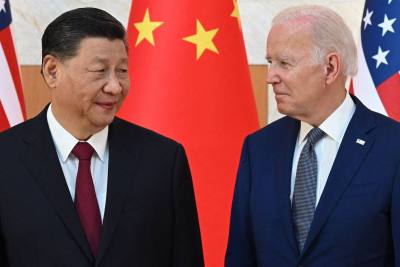

Seeing “China Evergrande Group” trending on global search engines is the last thing Xi Jinping needs as 2023 goes awry for Asia’s biggest economy.

News that exports plunged 14.5% in July year on year was the latest blow to China’s hopes of growing its targeted 5% this year. It’s the biggest drop since February 2020, when Covid-19 was sledgehammering trade and production worldwide.

Yet the default drama at Country Garden Holdings is a reminder that the call for help is coming from inside China’s economy.

This week, Country Garden was trending in cyberspace as it faced liquidity troubles akin to those of the humbled China Evergrande in 2021.

The whiff of trouble that tantalized markets in recent weeks proved true amid reports noteholders failed to receive coupon payments due on August 7.

That has global investors worried about an Evergrande-like domino effect. “If Country Garden, the biggest privately owned developer in China, goes down, that could trigger a crisis in confidence for the property sector,” says Edward Moya, senior market analyst for Oanda.

Analyst Sandra Chow at advisory firm CreditSights notes that “with China’s total home sales in the first half of 2023 down year-on-year, falling home prices month-on-month across the past few months and faltering economic growth, another developer default – and an extremely large one, at that – is perhaps the last thing the Chinese authorities need right now.”

The risk is slamming investor sentiment toward China. And it spotlights the urgent need for Chinese leader Xi and Premier Li Qiang to repair the shaky property sector and accelerate state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform.

A more vibrant and resilient property market is crucial to China’s economic recovery in the short run and reducing the frequency of boom-bust cycles in the longer run. The sector, if running smoothly, can generate as much as one-third of China’s gross domestic product.

Earlier this month, Li pledged to “adjust and optimize” Beijing’s approach to building a healthier, more stable property market. Li has urged major cities to devise measures to stabilize markets in their own jurisdictions.

That followed a pledge by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to provide developers with 12 additional months to repay their outstanding loans due this year.

This week’s default chatter raised the stakes. On August 3, Moody’s Investors Service slashed Country Garden’s credit rating to B1, putting it in the “high risk” category.

“This downgrade reflects our expectation that Country Garden’s credit metrics and liquidity buffer will weaken due to its declining contracted sales, still-constrained funding access and sizable maturing debt over the next 12 to 18 months,” says Moody’s analyst Kaven Tsang.

Country Garden’s stock has cratered over the last week after the company’s warning of an unaudited net loss for the first six months of 2023. Clearly, Country Garden has been grappling with liquidity chaos for some time.

As the company noted in a July 31 exchange filing, it “will actively consider taking various countermeasures to ensure the security of cash flow. Meanwhile, it will actively seek guidance and support from the government and regulatory authorities.”

A day later, Country Garden reportedly canceled an attempt to raise US$300 million by selling new shares.

As analysts at Nomura wrote in a note, “recent signals from top policymakers… suggest Beijing is getting increasingly worried about growth and have clearly recognized the need to bolster the faltering property sector. They are starting a new round of property easing and may introduce some stimulus to redevelop old districts of large cities.”

More important, though, is for Xi and Li to tackle the underlying cracks in the financial system. The sector’s troubles are structural, not cyclical.

Thanks partly to slowing urbanization and an aging and shrinking population, demand for new housing is on the wane. When economists worry about a Japan-like “lost decade” in China, the unfolding property crisis is Exhibit A.

The more that already massive oversupply increases, the more difficult it’s becoming for Beijing’s stimulus to flow through to construction activity.

And the more the property sector acts like a giant weight around the economy’s ankles, the more China’s financial woes look like Japan’s bad-loan crisis.

This dynamic is a clear and present danger to China’s ability to surpass the US in GDP terms, a changing of the economic guard many thought might happen as soon as the early 2030s. Yet so is the slow pace of SOE reform as China’s economic model shows growing signs of trouble.

Xi and Li clearly understand the urgency. In recent months, Xi’s Communist Party set out to help boost the valuations of SOE stocks, which represent a huge share of China’s overall market.

According to Goldman Sachs Group, SOEs in sectors from banking to steel to ports account for half the Chinese stock market universe. Yet Xi’s talk of creating a “valuation system with Chinese characteristics” is a work in progress, at best.

The SOE conundrum is a microcosm of Xi’s challenge to balance increasing the role of market forces and boosting investment in listed state companies, while also pulling more international capital China’s way.

In his second term in power, from 2018 to 2023, Xi more often than not tightened his grip on the economy at the expense of private sector development and dynamism.

The most drastic example was a tech sector crackdown that began in late 2020. It started with Alibaba Group founder Jack Ma and quickly spread across the internet platform space.

Since then, global money managers have grown increasingly more cautious about investing in Chinese assets. This, along with a steady flow of disappointing economic data, is undermining Chinese stocks, which are among the worst-performing anywhere this year.

That has given Xi and Li all the more reason to ensure that the practices of China’s largest state-owned giants come into better alignment with global investors’ interests and expectations.

China needs a huge increase in global investment to realize its vision for a 5G-driven technological revolution. Monetary stimulus can’t get China Inc there any more than Bank of Japan stimulus can revive Japan’s animal spirits.

Given the fallout from Covid-19 and crackdowns of recent years, China’s biggest tech companies are no longer cash rich or self-supporting. And the transition from SOE-driven to private sector-led growth has become increasingly muddled.

“If SOEs are able to pick and integrate the right targets, control risk effectively and promote innovation, outcomes should be credit-positive for the firms involved and beneficial for China’s growth,” says analyst Wang Ying at Fitch Ratings.

The global environment hardly helps, as evidenced by recent declines in export activity. US efforts to contain China’s rise – whether one calls it “decoupling” or de-risking” – is an intensifying headwind.

On August 9, US President Joe Biden detailed new plans to curb American investments in Chinese companies involved in perceived as sensitive technologies such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence.

Though nominally aimed at preventing US capital and expertise from flowing into mainland technologies that could facilitate Beijing’s military modernization, the limits are sure to have an added chilling effect on market sentiment.

Lingering pandemic fallout hardly helps. Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a Washington-based think tank, argues that China is suffering “economic long Covid” that could mean its condition is even weaker than global markets realize.

In a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Posen said that “China’s body economic has not regained its vitality and remains sluggish even now that the acute phase – three years of exceedingly strict and costly zero-Covid lockdown measures – has ended.

He warns that the “condition is systemic, and the only reliable cure – credibly assuring ordinary Chinese people and companies that there are limits on the government’s intrusion into economic life – can’t be delivered.”

Xi is, of course, trying. The campaign, which recently fueled a jump of over 50% in some SOE stocks, is accompanied by a slogan of buying into a “valuation system with Chinese characteristics.”

Last month, Chinese Vice Premier Zhang Guoqing said the government is redoubling efforts to deepen and hasten SOE reform.

Zhang, a member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China Central Committee, said the aim is to boost core competitiveness and prod SOEs to innovate, achieve greater self-reliance and raise their science and technology games.

More recently, Liu Shijin, a former vice minister and research Fellow of the Development Research Center, said government agencies must begin viewing entrepreneurs not as “exploiters” but as growth drivers.

But pulling off a transition toward private sector-driven growth would be much easier to pull off if China’s underlying financial system was more stable. The biggest risks start with the property sector.

“The problems of China’s property developers are only getting more severe,” says economist Rosealea Yao at Gavekal Dragonomics.

“The sales downturn is likely to throw many more private-sector developers into financial distress — a risk underscored by Country Garden’s recent missed bond payments. Unless sales can be stabilized, developers will be trapped in a downward spiral.”

Yao cites three reasons why a continued downturn in sales could push many private sector property developers into financial distress.

First, private developers have been mostly shut out of capital markets and thus unable to roll over maturing bonds since late 2021, when China Evergrande fueled investor concerns that other highly leveraged private sector developers would also be unable to repay their debts.

“Private sector developer issuance in the onshore bond market is now minimal, and has collapsed in the offshore market as well,” Yao says. “Companies with state ownership, by contrast, still mostly retain the faith of onshore bonds with bondholders demonstrating that they are not entirely risk-free.

“The combination of both weak revenues and lack of refinancing ability has led many firms to default or negotiate repayment extensions since the start of 2022, and the number of defaults and extensions remains elevated this year.”

Two, cash liquidity positions of private sector developers are deteriorating. According to the annual reports of 86 non-state-owned developers, she notes, short-term liabilities exceeded cash on hand by 725 billion yuan ($100 billion) in 2022, compared to a shortfall of 171 billion yuan ($23 billion) in 2021.

“This,” Yao says, “suggests that the firms may have insufficient liquidity to repay their maturing debts – though Country Garden boasted more cash on hand than its short-term liabilities at the end of 2022, suggesting this measure could understate the problem, as developer reserves may be shrinking rapidly this year.”

Third, many private-sector developers are not just illiquid – they are getting closer to insolvency. That is mostly due to rising impairment charges as the companies are forced to recognize that assets on their balance sheets have declined in value, often under pressure from auditors.

“Such charges deplete the asset side of companies’ balance sheets, pushing them closer to a situation in which the value of their liabilities could exceed the value of their assets — similar to the more traditional path to insolvency through negative net profits reducing equity,” she adds.

Again, Xi and Li clearly know what needs to be done to put China on more solid economic and financial ground. They just need to accelerate badly needed reform moves – before more indebted property developers like Country Garden hit investor confidence in the country’s prospects and direction.

Follow William Pesek on Twitter at @WilliamPesek

Man jailed for setting fire to neighbour’s HDB flat over prayer altar dispute

SINGAPORE: A man was jailed for 13 days on Thursday (Aug 10) for setting fire to a neighbour’s flat after a dispute over a prayer altar. Patrick Francis, also known as Pandian, pleaded guilty to one charge of mischief by setting fire to his neighbour’s main door past midnight onContinue Reading

Pakistan: Negotiate with PTM for stability

In the aftermath of rampant militancy and long military operations in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) led by Manzoor Pashteen emerged as a powerful socio-political force in the Pashtun belt of Pakistan.

The PTM as a prominent voice of war-butchered Pashtuns started peaceful struggle to advocate and ensure the due rights and security of Pashtuns in Pakistan. However, the myopic thinking of Pakistan’s powerful establishment, which seeks to silence or suppress the PTM, will pave way to detrimental consequences at ethnic and provincial levels.

By ignoring the legitimate grievances of the Pashtun community – demanding an end to enforced disappearances, profiling, extrajudicial killings, discrimination, and removing landmines in tribal areas, the establishment risks exacerbating ethnic tensions, fueling radicalization, and undermining the stability it seeks to establish.

The Pashtun belt, straddling regions in Pakistan and Afghanistan, has long been plagued by conflicts, political and economic marginalization, and the absence of state institutions. Pashtuns have faced a multitude of challenges, including terrorism, militancy, and subsequent military operations.

The rise of militancy, and the Pakistani military’s counter-operations in Swat and tribal region have resulted in the displacement of millions of Pashtuns, loss of thousands of lives, and destruction of infrastructure.

Undoubtedly, these factors have contributed to a sense of alienation and a lack of trust in the government and military. The PTM emerged as a response to these injustices, demanding a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, justice, and an end to enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

The PTM emerged in 2018 after the Karachi Police’s extrajudicial killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud, a young Pashtun from South Waziristan. The movement gained momentum as it highlighted the injustices faced by the Pashtun community, particularly in the FATA. The PTM’s demands for truth, justice, and an end to the culture of impunity resonated with the Pashtun population.

Silencing or suppressing the PTM would be a grave mistake as it would ignore the legitimate grievances of the Pashtun community. The federal government and military establishment fail to recognize that addressing these grievances is essential for achieving sustainable peace and security in the Pashtun belt.

By dismissing the PTM’s demands, the government and military risk alienating the Pashtun population further, and perpetuating a cycle of violence and instability.

The PTM plays a crucial role in countering radicalization by providing a peaceful platform for Pashtuns to voice their concerns and grievances. By suppressing the movement, the military establishment undermines this constructive outlet, and inadvertently pushes disillusioned Pashtuns towards more radical alternatives.

The PTM’s emphasis on non-violence and peaceful protest serves as a vital counter-narrative to extremist ideologies. Silencing the PTM would create a void that could be filled by radical elements equal to exacerbating security challenges in the Pashtun belt.

Evidently, Pakistan’s key security institution is moving wrong to recognize the importance of building trust and inclusivity in the Pashtun belt. By ignoring and countering the PTM, the establishment reinforces a perception of discrimination and marginalization among Pashtuns.

This further deepens the divide between the state and the Pashtun community, hindering efforts to establish a stable and secure environment. Embracing the PTM’s demands for inclusivity and addressing the grievances of the Pashtun community would foster trust, encourage cooperation, and contribute to long-term security stability.

Subduing the PTM could potentially escalate tensions in the Pashtun belt. The movement has garnered significant support, and mobilized a large number of Pashtun youth and intelligentsia who feel marginalized and victimized.

By attempting to silence the PTM, the federal government and military establishment risk provoking a backlash and further radicalization among Pashtuns. The grievances of the Pashtun community cannot be ignored or suppressed indefinitely, as doing so would only add fuel to existing tensions and potentially lead to violence.

For peace, dialogue and negotiation are essential in resolving the grievances of the Pashtun community. Instead of viewing the PTM as a threat, the civil-military leadership should engage in meaningful discussions to understand and address the concerns raised by the movement.

Open dialogue can lead to a better understanding of the issues at hand, and pave the way for mutually beneficial solutions. The use of power would serve to stifle dialogue, and perpetuate a cycle of violence and mistrust.

Without a single iota of doubt and confusion, it is utterly clear that the demands of the PTM are within the framework of the constitution of Pakistan.

One of the core demands of the PTM is an end to enforced disappearances. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, in the US, the Pakistani military launched large-scale operations against the militants in the former FATA.

Enforced disappearances on the basis of suspicion became routine. Thousands of Pashtuns have gone missing, with their families left in anguish and uncertainty.

By suppressing the movement, the military perpetuates a culture of impunity and denies justice to the victims and their families. This not only undermines the rule of law, but also fuels resentment and mistrust among the Pashtun population.

The government and military must acknowledge these grievances and take concrete steps to investigate and address cases of enforced disappearances.

The military operations in the Pashtun belt have resulted in the displacement of millions of Pashtuns. Many have lost their homes, lands, and livelihoods. Tens of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) are still living in BakaKhail camp in North Waziristan in an extremely poor state of life.

The rehabilitation of IDPs is crucial for building peace, stability and preventing the resurgence of militancy. The government can demonstrate its commitment to the well-being of the Pashtun community and pave the way for sustainable peace.

Moreover, the Pashtun belt has been a hotbed of militancy and terrorism for decades. The PTM’s demands for peace and stability align with the government’s objectives. By listening to the PTM, the military and government can gain valuable insights into the root causes of militancy and develop more effective strategies to counter it.

Involving the local population to tackle the menace of militancy will enhance intelligence gathering, build trust, and promote a sense of ownership over security matters.

Undeniably, the PTM is powerful. The chief of the PTM, Manzoor Pashteen, is powerful. He is the voice of millions of Pashtuns across Pakistan. His energetic anti-war narrative has preoccupied Pashtuns both emotionally and ideologically.

For Pashtuns, Manzoor is turning into a symbol of courage, resistance and Pashtunwali. Any intended attempt of the military establishment to derail or counter Manzoor Pashteen will prove disastrous and vibrantly dangerous on ethnic grounds. For stability, integrity and security, it is time to negotiate with the PTM.

Singapore Chess Federation ex-treasurer awarded S$120,000 in defamation suit over sexual misconduct allegation

FEMALE TRAINER’S RESIGNATION

One section of the defamatory letter referred to the resignation of a female chess trainer, Ms Anjela Khegay.

The letter alleged that Ms Khegay resigned from SCF on Aug 31, 2015 due to an “incident”, involving sexual misconduct of a verbal nature, at the federation’s Bishan office the day before. Ms Khegay subsequently filed a police report.

The letter further stated that Mr Nisban was one of two council members implicated in the incident, and that the president Mr Lau decided to withhold a report from other council members “despite the gravity of the matter”.

The reality was that Mr Nisban was in the room when the other council member who was implicated, Mr Tony Tan Teck Leng, made a remark to Ms Khegay which she found insulting.

On Jan 22, 2016, Mr Nisban’s lawyers sent a letter of demand to the 51 signatories, informing them that the statements in the letter were untrue and asking if they would dissociate from the statements.

Some subsequently withdrew their support. Mr Nisban sued the remaining for libel but 18 of them settled the matter, leaving the 21 defendants.

Not all 51 people who signed the requisition request were shown or had read the letter. Several claimed that they were only shown the signature sheet.

“SAME BRUSH OF SHAME”

In her judgment, District Judge Tan found that naming Mr Nisban in the letter “had the effect of tarnishing both council members with the same brush of shame”, even though Mr Nisban played a different role in the incident.

She ruled that a SCF member reading the letter would take it to mean that Mr Nisban was one of two council members accused by Ms Khegay of sexual misconduct; that the misconduct was serious enough to cause her to resign and lodge a police report; and that court proceedings could be pursued against them.

Most of the defendants argued that the word “implicated” in the letter merely meant “being involved”, but the judge said it was clearly meant to convey being involved in something bad or wrong.

“It cannot be argued that a statement to the effect that the plaintiff was accused of sexual misconduct and subject to police investigation would not lower the plaintiff in the eyes of right-thinking members of the SCF, or even the society at large,” District Judge Tan added.

Ms Khegay was also well-known in the SCF community, being a woman international master – the second-highest title in the chess world that is exclusive to women.

SCF members would be concerned about her sudden resignation, especially “chess parents” whose children she was training, said the judge.

The judge further noted that Mr Leong’s “unprecedented defeat” in the 2015 election was a shock to him, with “sufficient damning written evidence” that revealed his animosity towards his successor Mr Lau.

When it was suggested during the trial that the extraordinary general meeting that the letter called for was an act of revenge, Mr Leong did not deny it could be construed as such, said District Judge Tan.

She reiterated that Ms Khegay did not allege anything against Mr Nisban in her police report.

“In her resignation letter addressed to the SCF President, she had complained of the insulting and disturbing remark made to her by Tony Tan which she found to be totally unacceptable and inappropriate for any female,” the judge noted.

ISSUE OF MALICE

Mr Nisban also claimed the defendants had been motivated by political machinations and ill will as part of a plan to push through a vote of no-confidence in the SCF’s new leadership.

He also said there was a “hostile environment” within the executive council due to differences between two camps – Mr Leong and his supporters on one side, and on the other the likes of Mr Lau and Mr Nisban.

One defendant, Mr Kenneth Tan Yeow Hiang, showed his “complete indifference and reckless disregard” about the truth of the defamatory statements, said the judge.

He was a former SCF president as well as an ex-brigade commander in the Singapore Armed Forces. He also served as assistant managing director of the Economic Development Board, group managing director of UOB bank as well as director and chief of staff of Citibank.

The District Judge ruled that Mr Kenneth Tan, having failed to convince Mr Lau to voluntarily step down, signed the letter to support Mr Leong’s bid to oust Mr Lau and the executive council.

“His attitude in simply endorsing the requisition letter wholesale which he believed was prepared by Leong, or for which Leong was mainly responsible, without proper verification of the sexual misconduct allegations is evidence of malice,” she said.

‘COMBATIVE ATTITUDES’ DURING TRIAL

In determining the amount of damages to award Mr Nisban, the judge accepted his argument that the sexual misconduct accusations were particularly grave because they called his character and decency into question.

His wife and sons also “had to bear the shame and embarrassment” of being linked to the allegations, especially since Ms Khegay coached his son, said District Judge Tan.

While Mr Nisban was not a public leader or well-known figure in Singapore, he was well-known within the SCF community and had a reputation to protect.

As for aggravated damages, the judge said this was clearly warranted due to the defendants’ conduct during the trial. They also raised defences that were reckless or bound to fail.

“The trial also revealed the combative attitudes, as well as the disdain and contempt displayed by a number of the defendants towards the plaintiff,” she added.

For example, Mr Alphonsus Chia, former vice-president of Singapore Airlines and ex-CEO of defunct carrier SilkAir, insisted that Mr Nisban “cooked up” the accusation in the letter. He also challenged Mr Nisban to “bring it on”.

The defendant Mr Kenneth Tan also openly declared that Mr Nisban was a “less than straight” person, added District Judge Tan.

She ordered that all parties file submissions on the issue of costs.

The trial spanned 22 days and was spread across February 2021 to October 2022. Mr Nisban was represented by Mr Lau Kok Keng, Mr Daniel Quek and Ms Edina Lim from law firm Rajah & Tann Singapore.

Woman accused of assaulting preschool toddlers and trapping them in dark room, behind table

SINGAPORE: A woman is accused of abusing two toddlers at a preschool by trapping them either in a dark storeroom or behind a table, as well as assaulting them.

A second woman is accused of allowing one of the children to be ill-treated on one occasion.

The two accused parties and the preschool cannot be named in order to protect the two victims.

The alleged abuser, 28, was given six charges on Aug 3 of ill-treating two children in her care under the Children and Young Persons Act.

She is accused of trapping a two-year-old boy under a table at the preschool for about 15 minutes on Jun 22, 2022.

She then placed him inside a dark storeroom for six to seven minutes, before throwing four foam blocks into the storeroom from above while he was trapped inside, charge sheets allege.

That same day, she allegedly poked the face of a girl who was one year and eight months old, before slapping her face and pulling her onto her feet to push the child to the ground multiple times.

She also allegedly hit the girl’s face with foam blocks, rubbed tissue paper into her face forcefully, slapped her and pinched her cheeks violently.

The woman is accused of abusing the two toddlers again on a second occasion on Jun 27, 2022.

She allegedly pulled a chair that the two-year-old boy was seated on, causing him to fall to the ground. She then placed him on a chair and pushed him into a table.

That same morning, the woman allegedly shoved a table laden with objects onto the girl, trapping her. She then shoved the table multiple times into the girl who was one year and eight months old at the time.

Over about half an hour, the woman allegedly hit the girl multiple times on her face with a plastic divider while the toddler was trapped behind and underneath the table.

About 10 minutes after this, the woman allegedly turned her attention back to the boy, pinching his face forcefully and slapping him.

The woman’s lawyer told the court when she was charged that she was five months pregnant.

The second woman involved, also aged 28, faces one charge of failing to protect the girl from being ill-treated. This was in relation to the incident where the girl was hit with a plastic divider.

The cases are pending. The penalty for each charge of ill-treating a child under the Children and Young Persons Act, or permitting such ill-treatment, is a jail term of up to eight years, a fine of up to S$8,000, or both.

A neocolonial history of the UN Security Council permanent five

One of the underlying principles of the UN Charter is the protection of the sovereign rights of states. Yet since 1945, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the Soviet Union/Russia, France, the UK, the US and China) have consistently used military force to undermine this notion.

And while acts of seizing territory have grown rare, ongoing military domination allows imperialism to manifest further through economic, political, and cultural control.

System justification theory helps explain how policymakers and the public defend and rationalize unfair systems through the surprising capacity to find logical and moral coherence in any society.

“Reframing” neocolonial policies to reinforce system-justifying narratives, often by highlighting the need to defend historical and cultural ties and maintain geopolitical stability, has been essential to sustaining the status quo of international affairs.

Naturally, the five UNSC members have often accused one another of imperialism and colonialism to deflect criticism from their own practices. Yet prolonging these relationships in former colonies or spheres of influence simply perpetuates dependency, hinders economic development, and encourages instability through inequality and exploitation.

France

In response to comments made by Russia’s Foreign Ministry in February, which singled out France for continuing to treat African countries “from the point of view of its colonial past,” the French Foreign Ministry chastised Russia for its “neocolonial political involvement” in Africa.

The previous June, French President Emmanuel Macron had accused Russia of being “one of the last colonial imperial powers” during a visit to Benin, a former French colony that last saw an attempted coup by French mercenaries in 1977.

Independence movements in European colonies grew substantially during World War II, and Paris granted greater autonomy to its possessions, most of them in Africa, in 1945. Yet France was intent on keeping most of its empire, and became embroiled in independence conflicts in Algeria and Indochina.

Growing public sentiment in France, since referred to as “utilitarian anti-colonialism,” meanwhile promoted decolonization, believing that the empire was actually holding back France economically and because “the emancipation of colonial people was unavoidable,” according to French journalist Raymond Cartier.

France left Indochina in defeat in 1954, while in 1960, 14 of France’s former colonies gained independence. And after Algeria won its independence in 1962, France’s empire was all but gone.

But like other newly independent states, many former French colonies were unstable and vulnerable to or reliant on French military power. France has launched dozens of military interventions and coups since the 1960s in Africa to stabilize friendly governments, topple hostile ones, and support its interests.

French military dominance has been able to secure a hospitable environment for French multinational companies and preferential trade agreements and currency arrangements. More recently, the French military has consistently intervened in Ivory Coast since 2002, as well as in the countries of the Sahel region (particularly Mali) since 2013, and the Central African Republic (CAR) since 2016.

The French-led campaigns have received significant US help. Speaking in 2019 on the French deployments, Macron stated that the French military was not there “for neo-colonialist, imperialist, or economic reasons. We’re there for our collective security and the region.”

But growing anti-French sentiment in former colonies in recent years has undermined Paris’ historical military dominance. Closer relations between Mali and Russia saw France pull the last of its troops out of the country in 2022, with Russian private military company (PMC) forces replacing them.

A similar situation occurred in the CAR months later, and this year, French troops pulled out of Burkina Faso, with Russian PMC liaisons having reportedly been observed in the country.

Frustration with the negative effects of France’s ongoing influence in former colonies has also been directly tied to problems in immigrant communities living in France. The fatal shooting of a North African teenager by police in the suburbs of Paris this June caused nights of rioting, with Russia and China accusing France of authoritarianism for its security forces’ response.

United Kingdom

Shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the UK’s prime minister at the time, Boris Johnson, denounced the Russian president for still believing in “imperial conquest.” Yet like France, the UK has often been accused of using military force to help promote British interests in its former empire, including the dominant role of British banks and financial services and other firms, for decades.

As the only European colonial power not defeated by Nazi Germany, British forces were sent to secure Indochina and Indonesia before French and Dutch forces could return after World War II. But London’s focus soon turned to protecting its own empire and emerging independent states.

British forces helped suppress a communist insurgency in Malaya from 1948-1960, fought in the Kenya Emergency from 1952-1960, and intervened across former colonies in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and Pacific islands.

Additionally, British, French and Israeli forces invaded Egypt in 1956 after the Egyptian government nationalized the Suez Canal, before diplomatic pressure from the US and the Soviet Union forced them to retreat.

Over the next few decades, almost all former British colonies were steadily granted independence, and by 1980 the rate of British military interventions abroad had slowed.

Nonetheless, the 1982 Falklands War somewhat reversed the perception of the UK as a declining imperial power. The successful defense of the Falkland Islands’ small, vulnerable population against Argentine aggression enhanced the perception of the UK as a defender of human rights and champion of self-determination.

Additionally, Britain’s focus on naval power “was important to the self-image of empire,” as naval strength is often perceived as less threatening than land armies. Prominent British politicians such as former prime minister David Cameron have similarly restated Britain’s commitment to protecting the Falklands from Argentine colonialism.

More recently, the British military intervened in the Sierra Leone Civil War in 2000 and was also a crucial partner for the US-led wars in Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. And alongside ongoing official deployments, British Special Forces have been active in 11 countries secretly since 2011, a report by Action Against Armed Violence revealed.

The residual presence of the British military has often made it difficult to embrace the “new and equal partnership” between Britain and former colonies, championed by former British foreign minister William Hague in 2012.

The domestic perception of Britain’s colonial legacy continues to play a divisive role in British politics and society. Winston Churchill, the winner of a 2002 BBC poll on the top 100 Great Britons, was “cited as a defender of an endangered country/people/culture, not as an exponent of empire.” Yet during anti-racism protests in the UK in 2020, a statue of the former prime minister was covered up to avoid being damaged by protesters.

Believing him to be a figurehead of the cruelty of British colonialism, the covering up of Churchill’s statue shows the contrasting and evolving domestic views of British imperialism.

Soviet Union/Russia

After 1945, Soviet troops were stationed across the Eastern Bloc to deter the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and suppress dissent. Several military operations in support of communist governments against “counterrevolutionary” protesters were approved in East Germany (1953), Hungary (1956), and Czechoslovakia (1968).

Soviet forces also took part in a decade-long conflict to prop up Afghanistan’s government from 1979-1989.

In Asia, Africa and Latin America, however, the Soviet Union presented itself as the leading anti-colonial force. It proclaimed an ideological duty financially, politically, and militarily to support numerous pro-independence/communist movements and governments, tying these efforts to confronting the colonial West.

The collapse of the USSR forced Moscow to prioritize maintaining Russia’s influence in former Soviet states. But even today, many Russians do not see the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire as empires, as Russians insist that they lived alongside their colonized subjects through a “Friendship of Peoples,” unlike the British or French.

This sentiment drives much of the rhetoric defending Russia’s ongoing dominance across parts of the former Soviet Union.

On the eve of the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin once again called into question Ukrainian statehood. Ukraine, like other former Soviet states, has often been labeled an artificial creation by Russian politicians.

Alongside the necessity of military force to protect Russian speakers/citizens, Russian officials have justified conflict and exploitation of fragile post-Soviet borders in separatist regions of Georgia, Moldova, and Armenia/Azerbaijan since the early 1990s.

Russia has also worked to maintain a dependency on its military power in former Soviet states. The Kazakh government’s reliance on the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization military alliance was clearly demonstrated during the CSTO intervention amid protests in January 2022.

Prominent Russian politicians such as Sergey Lavrov have consistently compared the CSTO favorably to NATO, but the lack of support from CSTO member states (except for Belarus) for Russia in its war with Ukraine has demonstrated its limitations.

The Russian military has also been active in Syria since 2011, while dozens of Russian PMCs have increased operations across Africa over the past decade. The Kremlin is increasingly tying these conflicts, as well as Russia’s war in Ukraine, to reinforce Moscow’s traditional role as an anti-colonial power.

Russia has performed significant outreach to Africa since the start of the war, and at the annual St Petersburg Economic Forum this year, Putin declared the “ugly neocolonialism” of international affairs was ending as a result of its war.

By amplifying criticism over the domination of global affairs by the “Golden Billion” in the West, the Kremlin believes it can blunt foreign and domestic criticism over its war in Ukraine, as well as over its approach to other post-Soviet states.

United States

The USA, born out of an anti-colonial struggle, has naturally been wary of being perceived as a colonial power. US presidents voiced support for decolonization after World War II, particularly John F Kennedy. But because “anti-communism came before anti-colonialism,” Washington often supported neocolonial practices by European powers to prevent the spread of Soviet influence and secure Western interests.

The US has also been criticized for its own imperial behavior toward Latin America since 1823, when the Monroe Doctrine was first proclaimed. The United States’ sentiment that it had a special right to intervene in the Americas increased during the Cold War as Washington grew wary of communism.

US military forces intervened in Guatemala in 1954, Cuba in 1961, the Dominican Republic in 1965, Grenada in 1983, and Panama in 1989 to enforce Washington’s political will.

The US war on drugs, launched in 1969, also destabilized much of Latin America, while other instances of covertly fostering instability have prevented the emergence of strong sovereign states in the region.

Major foreign conflicts involving US forces since 1945 include the Korean War (1953-1953) the Vietnam War (1955-1975), the Gulf War (1991), intervention in the Yugoslav wars (1995, 1999), and the “war on terror” (2001-present).

US forces also intervened in Haiti in 1994-1995 during “Operation Uphold Democracy” and again in 2004, while leading international interventions in Libya (2011) and Syria (2014). These interventions have often been criticized for perpetuating instability and weakening local institutions.

Nonetheless, the global US military presence has continued to grow. Since 2007, United States Africa Command (AFRICOM) has seen the US expand its military footprint across Africa and today, 750 known military bases are spread across 80 countries.

US special operations forces are estimated to be active in 154 countries. The US global military presence also gives Washington considerable control over transportation routes, with the US Navy routinely seizing ships violating trade restrictions.

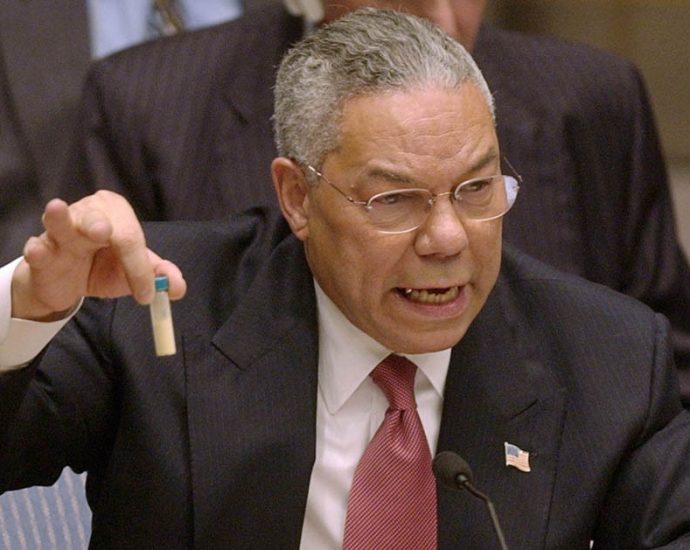

US officials have continued to lean on the country’s history as a former British colony to highlight solidarity with other countries and propose greater cooperation. In 2013, for example, then-secretary of state John Kerry said the Monroe Doctrine, which allowed the US “to step in and oppose the influence of European powers in Latin America,” was over.

And in an address this year from the White House briefing room proclaiming the start of Caribbean-American History Month, President Joe Biden noted how the US and Caribbean countries are bound by common values and a shared history of “overcoming the yoke of colonialism.”

But domestic divides over Washington’s role in global affairs have increased calls for the US to return to its early foreign policy of isolationism. While this will not be enough for the US to retreat on the global stage, it has helped prevent its military from committing to new major conflicts in recent years.

China

The conclusion of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 marked the end of China’s “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of European powers, the US, and Japan. The victory of the Communist Party of China (CPC) allowed Beijing to consolidate power and look toward expanding China’s borders.

This included launching the “peaceful liberation” of Xinjiang in 1949 and Tibet in 1950, steadily bringing these regions under China’s control – though China only took Taiwan’s seat at the UN in 1971.

China’s history of exploitation by foreign powers has frequently been cited by Beijing to increase solidarity with other countries that suffered from Western imperialism.

Key to this messaging was fighting against US-led forces in the Korean War, as part of a “Great Movement to Resist America and Assist Korea” and opposing wider Western neocolonialism, while Chinese forces also engaged in border clashes with the Soviet Union as relations between Moscow and Beijing soured in the 1960s.

But Chinese forces have also been involved in clashes with former European colonies. This includes confrontations with India, as well as China’s launch of a major invasion of northern Vietnam in 1979.

Tens of thousands of casualties were recorded on both sides during the month-long operation, while continued border clashes between Chinese and Vietnamese forces continued until relations were normalized in 1991.

Since 2003, Chinese officials have instead placed great emphasis on China’s “peaceful rise,” which has seen the country drastically increase its power in world affairs without having to resort to military force.

But while large-scale Chinese military operations have not materialized, China has rapidly increased the construction of ports, air bases, and other military installations to enforce its territorial control over the South China Sea over the past decade, at the expense of several Southeast Asian countries.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has justified these developments because the islands “have been China’s territory since ancient times.”

China’s extensive maritime militias and civilian distant-water fishing (DWF) fleets have also been accused of asserting Chinese maritime territorial claims while blurring the lines between civilian and military force.

Additionally, there is fear that China’s growing economic and military might will be enough to force countries in Central Asia to accept the Chinese position on various territorial disputes.

While China has avoided any major military operations this century, it has used its growing economic and military might to pressure other countries into accepting its territorial claims. To offset criticism, Chinese officials have turned their attention toward ongoing and historical imperialism by the West.

After British criticism over Beijing’s handling of pro-democracy protests in 2019, China criticized the UK for acting with a “colonial mindset,” and, in support of Argentina, accused the UK of practicing colonialism in the Falklands in 2021.

These claims help sustain domestic support for China’s policies, help to increase solidarity among other countries which have suffered from Western imperialism, and put China’s geopolitical rivals on the defensive.

Conclusions

It is true that the US military provides necessary security deterrence to numerous countries, and has also proved essential to responding to natural disasters and other emergencies. But like other major powers, the use of US military force has consistently been abused since 1945.

The historical legacy of Western imperialism and interventionism has helped explain why Western calls for global solidarity with Ukraine have often fallen on deaf ears.

Additionally, some of the consequences of the war in Ukraine, including rising energy and food prices, are being most acutely felt in poorer countries, while the growing dominance of Western firms in crucial Ukrainian economic sectors has also undermined the West’s messaging over Ukraine further.

Honest accountability by major powers for the historical and ongoing exploitation of weaker countries remains rare. But public, government-funded initiatives such as the US Imperial Visions and Revisions exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington document the beginning and justification behind empire-building in the US, and is an important step to addressing past and contemporary wrongdoing, as envisaged by the UN Charter in 1945.

In 2018, French President Macron commissioned a report that discovered that “around 90-95% of African cultural heritage” was located abroad, prompting the French parliament to pass a bill in 2020 allowing these artifacts to be returned.

The promotion of actual history and accountability may also remove barriers to more selfless assistance to weaker countries by major powers.

This approach could, in turn, invite greater cooperation and positive repercussions than costly military interventions, and would also serve as an example for weaker states grappling with their own legacies of violence, exploitation and suppression.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, which provided it to Asia Times.

No Signboard Holdings CEO suspended until resolution of price rigging charges

SINGAPORE: The chief executive officer of No Signboard Holdings has been suspended from all executive duties after being charged with price rigging offences, said the restaurant operator in a filing on Tuesday (Aug 8). Sam Lim Yong Sim, who is also the executive chairman of the company, was charged on JulContinue Reading

Indonesian maid’s torture highlights lack of legal protections

“Demanding protection from other countries while we have not fulfilled the responsibilities ourselves is like a slap in our face.” Despite the risks and horrifying stories of abuse, women from rural areas like Khotimah feel compelled by poverty to keep moving to big cities for work. “We owed money inContinue Reading

Japan ex-PM’s ‘fight for Taiwan’ remark in line with official view, lawmaker says

TOKYO: Former Japanese Prime Minister Taro Aso’s remark on Tuesday (Aug 8) that his country must show “the resolve to fight” to defend Taiwan from attack was in line with Tokyo’s official stance, a lawmaker close to Aso told a TV show late on Wednesday. Aso, vice president of theContinue Reading

Flights cancelled as Storm Khanun hits South Korea

BUSAN: Hundreds of flights and high-speed trains were cancelled and businesses shuttered in the South Korean port town of Busan after Tropical Storm Khanun made landfall on Thursday (Aug 10), bringing heavy rain and high winds. The storm, which battered Japan before taking a circuitous route towards the Korean peninsula, madeContinue Reading