Less than two years since the military coup that triggered a new era of civil war, Myanmar’s democratic resistance is pushing for a swift conclusion to a still escalating conflict.

In a high-risk move that effectively defines the dry season of early 2023 as decisive for the country’s future, the shadow National Unity Government (NUG) issued a statement in mid-October calling for the victory of the “Spring Revolution” aimed at overthrowing the decades-long hegemony of the armed forces by the end of next year.

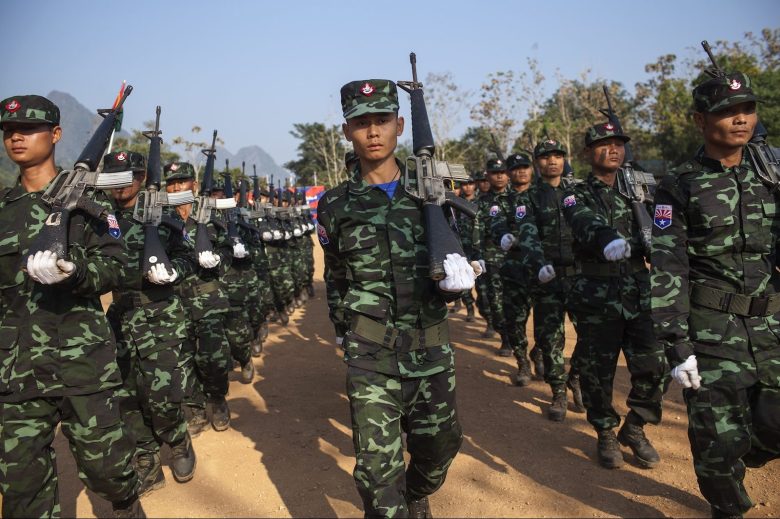

That call was followed up by predictions of stepped-up fighting in urban areas which appeared to find a ready response in eastern Karen state. In what looked briefly like the first seizure of a major town by the anti-junta resistance, units of the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) and allied Peoples Defense Forces (PDFs) fought their way into Kawkareik town on the main highway linking Yangon and Myawaddy on the Thai border.

“There’s clearly a high degree of urgency,” noted one foreign intelligence analyst closely monitoring the conflict. “The NUG feel they have to get this done quickly – within a year.”

There appear to be several reasons behind the perceived need to rapidly conclude the war, despite its only beginning in earnest in the final quarter of last year.

One driver is undoubtedly the looming prospect of the “multi-party discipline-flourishing” elections planned by the coup regime’s State Administration Council (SAC) for August 2023, and fears that polls, however flawed, might confer a measure of international legitimacy on a government fronted by men dressed in civilian longyis rather than army khakis.

From its inception in February 2021, the SAC has defined elections held on its terms as the best, indeed only, path for the armed forces to withdraw from centerstage of Myanmar’s politics. An elected parliament and pliant quasi-civilian coalition government would then – at least in theory – permit reforms to the military’s 2008 constitution calculated to appeal to Myanmar’s ethnic parties and armed organizations.

At the same time, any civilian administration with claims to have emerged from a ballot box may provide foreign states that prefer stability over war in Myanmar with the fig leaf they need to resume engagement.

That bloc comprises not only the SAC’s sworn authoritarian allies in Moscow and Beijing but also a far wider grouping that would likely include Iran, Pakistan, several Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) states and conceivably democratic India and even Japan.

Further pressure to accelerate the conflict also likely stems from concerns over how long popular support for an increasingly violent struggle can be sustained under desperate economic circumstances that, according to United Nations estimates, will see nearly half of the 55 million population subsisting below the national poverty line this year.

Finally, with support from Western democracies and international bodies limited to vacuous statements of boilerplate outrage over the regime’s excesses of the week, the financial and military constraints faced by the NUG argue for speed rather than the uncertainties of protracted war.

“If they wait too long, they simply may not have the money to pull it off,” reflected the same intelligence analyst.

Derived largely from the donations of domestic supporters and a range of innovative NUG-generated fund-raising schemes, that hard cash is crucial for weapons procurement, humanitarian aid to conflict-impacted areas and support for a plethora of local PDFs that in turn translates into more effective centralized command-and-control.

Accelerating risks

Even against the backdrop of these pressures, however, the push for a rapid revolutionary victory within the coming ten months poses daunting risks. Put simply, the danger is of PDFs, either alone or supported by ethnic allies, attempting to run before they can walk and falling hard on their faces.

In military terms that scenario means loosely organized guerrillas lacking sufficient coordination, training, support weaponry or anti-aircraft defenses taking on well-equipped regime forces fighting with their backs to the wall.

Modern conflicts are littered with lessons learned in blood by even well-organized and experienced revolutionary forces attempting prematurely to transition from guerrilla tactics to semi-conventional operations against entrenched regimes. Historically, those attempts have typically been born of real or perceived political pressures and an underestimation of an enemy judged to be close to collapse.

A notably disastrous example of the “rush-to-victory” syndrome was the early 1951 attempt by celebrated Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap to breach the Red River Delta redoubt established by French colonial forces to screen the capital Hanoi.

The startling human losses incurred in a three-month campaign – the first time that napalm was airdropped to devastating effect on massed infantry – nearly cost Giap his career and severely set back a war that was not finally won by the anti-colonial Viet Minh until a far better-prepared battle was joined at Dien Bien Phu three years later.

A later chapter of Vietnam’s revolutionary struggle saw Viet Cong forces launch their January 1968 Tet Offensive across South Vietnam in the heady expectation of triggering popular uprisings. In the upshot, communist military infrastructure built up over a decade in the South was decimated in two weeks by American and allied Saigon forces: the war finally won in 1975 was a victory not of the crippled Viet Cong but of the North Vietnamese Army.

Politics and over-confidence drove a similar debacle on the other side of Asia when in the spring of 1989 anti-communist Afghan guerrillas made a quick lunge for victory. Urged on by a Pakistani intelligence service eager to install a provisional opposition government following the withdrawal of Soviet forces, mujahideen factions sought to trigger the collapse of Kabul’s communist regime with weeks of frontal assaults on the eastern city of Jalalabad.

Untrained tribal fighters were beaten back in disarray by well-equipped regime ground forces fighting for survival and supported by round-the-clock airstrikes. The collapse of President Mohammad Najibullah’s government came only three years later following internal division driven by the end of Soviet funding.

In the Myanmar context, the danger of setbacks on this scale for forces manifestly unprepared for frontal offensives lies in the potentially disastrous impact on popular morale and the absence of any obvious alternative avenues to victory.

To date, even assaults involving relatively well-armed coalitions of PDF and ethnic resistance organizations (EROs) have notably failed to take urban areas in the face of counterattacks relying on multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS) and repeated air strikes launched by a regime determined not to lose urban centers.

The challenge was starkly illustrated first in and around the Kayah state capital of Loikaw in January and again in September around Moebye on the Kayah border with Shan state.

And in October the battle for Kawkareik straddling the road to the Thai border drove home the same lesson: air strikes and artillery still rule.

Meanwhile, in other western regions of Sagaing and Magway where PDFs mostly operate without direct ERO support, resistance forces have to date been unable or unwilling to overrun – even briefly – relatively small township centers.

Against this sobering backdrop, calls for victory in 2023 risk raising unrealistic expectations and counter-productive consequences: quixotic assaults on fixed positions entailing heavy casualties among popular resistance forces that still lack the organizational cohesion and leadership to absorb them.

A worst-case scenario could involve strategic setbacks from which the anti-military democracy movement might take years to recover.

What is to be done?

An arguably more realistic approach to navigating the disconnect between shortening time constraints and still under-developed capacity would prioritize a progressive escalation of offensive capabilities and operations aimed at using the coming year to build convincing military momentum which at present has yet to coalesce.

Achieving visible impetus on the battlefield would act both to reinforce domestic support should it begin to flag while steadily eroding already brittle morale in SAC ranks. At the same time, palpable successes would demonstrate to a still skeptical international community that the Naypyidaw regime is confronting, in some shape or other, the inevitability of military disintegration and political defeat.

As events since the coup have already made clear, successful resistance to military rule can only be built on the foundation of a fighting alliance between the ethnic Bamar-dominated NUG and Bamar PDFs more generally on the one hand, and, on the other, ethnic resistance organizations – Kachin, Chin, Karen, Karenni, Shan, Rakhine and potentially others – without whose active support and participation the war cannot be won.

Solidifying that alliance in preparation for the militarily critical months ahead will in turn require establishing – and fast – a far deeper level of trust than exists today to bridge a wide historical divide. The onus of setting to rest ERO doubts over Bamar commitment to a new federal compact will rest squarely on the NUG and those in it from the previous National League for Democracy (NLD) administration of imprisoned State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi.

The bleak record of born-to-rule Bamar arrogance that characterized the NLD government and underpinned its failure to understand, let alone address, ethnic grievances has left a legacy that continues to fester. Those doubts were pointedly captured in one major ERO’s scathing references earlier this year to the current conflict as a “power struggle between Bamars.”

At this juncture, any failure by the older generation of NLD politicians at the core of the NUG to “go the extra mile” in assuaging ERO skepticism could yet prove disastrous to the success of a revolutionary war that has already moved Myanmar beyond the era of Suu Kyi and the evolutionary politics she personified.

Addressing in the coming weeks touch-stone ethnic concerns such as state constitutions in a future federation – notably opposed by Suu Kyi when in government – will be crucial.

Peoples Assault Units

If the foundation of an ethnic political accord can be stabilized, any military strategy for 2023 would almost certainly need to be spearheaded by the organization of streamlined military units configured specifically for strategically targeted offensive operations.

The formation of new “Peoples Assault Units” (PAUs) built on existing Peoples Defense Forces but distinct from them in terms of equipment, trained personnel and mobility would mark a clear dividing line between past and future phases of the war.

Optimally, PAUs might begin operating as company-sized commando groups of 200-250 troops, equipped on a priority basis as standardized units with an adequate range of support weaponry such as machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and mortars. And what for now these semi-regular companies would lack in air defense, they would need to compensate for with camouflage and a facility for rapid dispersal.

Coordinated at least across regions or states and in the coming months specifically avoiding futile and costly attempts at overrunning population centers, PAU operations would be directed either by the NUG Defense Ministry’s Central Coordinating Committee (CCC) or allied EROs and might best focus on three primary target sets.

The low-hanging fruit is already entirely visible: a multitude of outlying army or militia positions, typically undermanned and ill-supplied. Attacks on such outposts have already begun during the monsoon season just ended, notably in Karen and Kayah states but also in southern Chin and northern Rakhine where since late August the Arakan Army (AA) has begun isolating and picking off exposed army positions in Paletwa and Maungdaw townships.

To date, however, such operations have not been integrated into a broader strategy specifically planned to stretch regime response capabilities, not least in terms of air power.

Where assaults have been repulsed — as with the protracted attempt by Karen forces to overrun the Ukayit Hta outpost near the Thai border in late June and early July — has been due to a failure to concentrate sufficient forces to rapidly overrun a position before the mobilization of air power swings the balance decisively against the attackers.

Secondly, assault units would be well deployed to conduct commando raids in strength targeted on critical military infrastructure: fuel supply depots, munitions plants, airbases and training facilities.

With planning, reconnaissance and intelligence at a premium, such raids would ideally exploit the cover of darkness to hit hard, destroy specific targets and withdraw without attempting to hold ground.

Military movement along major road and rail lines of communication, the Achilles Heel of any incumbent regime, offers a third target set. Conducted by local PDFs on an ad hoc basis, harassment of army convoys using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) has been a staple resistance tactic since the early days of the uprising in mid-2021.

By contrast, the deployment of well-equipped assault units would be aimed at interdicting and destroying convoys while, as a secondary benefit, tying down regime forces in small and thus highly vulnerable highway security outposts.

Depending on location, such ambushes would need to exploit a short window of perhaps 45 minutes between an initial contact and the arrival of close air support in the shape of Mil Mi-35 or newly acquired Kamov KA-29 attack helicopters.

War in the balance

Whether offensive operations might in the year ahead shift from an indirect strategy of systematically stretching and weakening the military to direct seizures of population centers is almost impossible to predict.

In what is likely to be an extremely fluid situation over the coming dry season that shift would hinge on variables on both sides of the conflict without even referencing possible surprise external factors.

Operational coordination across regions and states, and the evolution of military capabilities not least regarding air defense, would both be decisive for forces ranged against the junta. The effectiveness with which communications arteries can be interdicted would also play a crucial role.

For the SAC regime, the impact of rapidly growing demands on the Myanmar Air Force to compensate for the shortcomings of embattled ground forces will weigh as a central factor. The availability or otherwise of airframes, trained pilots, spare parts, munitions, fuel and not least secure bases will all play into a fluid mix.

But as the war moves towards perhaps its most decisive phase, the outcome will likely rest largely on two overarching factors: the political willingness of the NUG convincingly to turn away from a corrosive legacy of Bamar chauvinism and military planning that avoids a rush to victory that could well spell defeat.