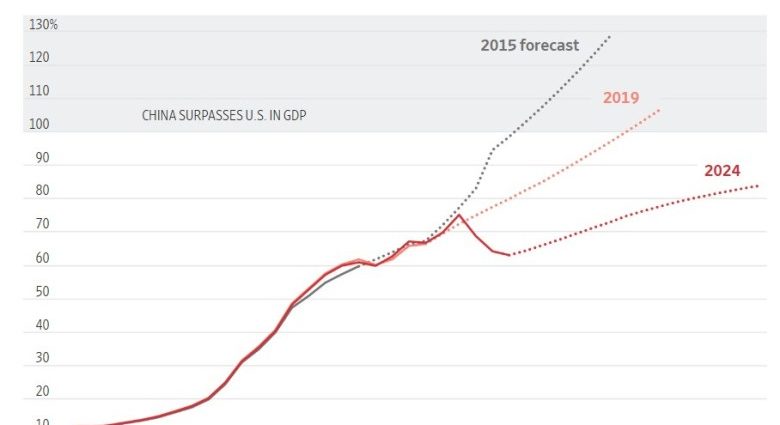

Many people are really interested in the results of comparisons between the markets of different countries, and it is a popular game. For instance, I see a lot of people passing around charts , like this one, claiming to demonstrate that China’s economy has fallen behind the US ‘ since 2021:

In the WSJ, Jason Douglas and Ming Li present a more in-depth type that shows how estimates of the two markets ‘ styles have changed over time.

In Bloomberg, Hal Brands , cites this data , to support his argument that the US is also back of China in terms of international power:

People predicted that China would immediately overtake the US as the world’s largest economy. But that crossing place is receding ever further into the future, thanks to strong British growth and deepening Foreign stagnation…Over the previous half-decade, the overall , gap , between the US and Taiwanese economies — as measured by gross domestic product — has been getting larger.

Therefore, if you only take a look at this information, you might get the feeling that China’s economy is struggling and won’t be able to catch up. But then if you read the news, you hear that China’s GDP is , growing at a rate of “around 5 %”, while the US , grew at only 3.1 %  , in 2024. That’s a solid year for the US, but it’s not obvious how China’s economy may be falling behind America’s if its growth rate is higher!

The issue here really has nothing to do with whether or not China’s GDP progress is overstated. Yes, it’s probable that this is the circumstance— for instance,  , Rhodium Group guesstimates , that China’s real rise in 2024 was under 3 %. But the figures above truly get the Chinese administration’s 5 % figure at face value. So why do they depict China laggarding America?

There are many different ways to compare GDP, which is the true cause of the gap. The two fundamental steps are:

- GDP at , business exchange rates, likewise called “nominal”

- GDP at , purchasing power parity ( PPP ), also called “international dollars”, also called” adjusted for differences in the cost of living”

If you use the second of these steps, you see China’s GDP falling behind America’s, as in the two figures below. But if you use the following estimate, you see China’s GDP now ahead of America’s, and pulling further away every year ( albeit at a slower rate than before 2021 ):

You’ll see that this table says” adjusted for…differences in the cost of living between places”, and “international$”. That means PPP.

GDP is expressed in US money at the marketplace exchange rate. You only get a government’s GDP numbers ( which are measured in its domestic money ), change that amount to money using the latest exchange rate, and that’s the country’s “nominal” GDP.

That’s really easy to calculate and calculate. However, it implies that when exchange rates change, it appears that different economies ‘ relative sizes even change, despite producing exactly the same amount of goods as before. In this instance, it turns out that China’s yuan or RMB has been depreciating against the US dollars for centuries.

Here is a chart of the amount of currency one Chinese yuan you purchase:

You’ll notice that the yuan’s price decreased significantly in late 2021 despite being a little weak in the first half of the year. That’s a big part of the reason that China’s nominal GDP fell equivalent to America’s over the last three decades. The decline in China’s established real progress rate was  , part , of the decline, but much of it was only an effect of the cheaper renminbi.

In fact, assuming the renminbi stays low, the prediction for China’s ability to get up to America over the next 15 years are almost certain. If the yuan appreciates, China’s nominal GDP will immediately appear like it jumped off.

In reality, if China lets the yuan fall a bit, it will look like China’s economy immediately overtook America’s in size — this is what happened in the late 1980s when Japan allowed its yen to understand, and Japan’s nominal GDP suddenly , looked like it was almost as big , as America’s.

There is debate about whether market exchange rates are effective for comparing nations’ GDP. On one hand, it’s easy to measure, because exchange rates themselves are clear and unambiguous. And if you care about imports, the number of items that can be purchased by two different nations is undoubtedly the best thing to look at in terms of GDP at the market exchange rate. When China’s currency gets weaker, it means China can afford fewer imports.

So if you’re in a third country like South Korea, and you’re asking,” Which is a more important market for my goods, China or America”?, the answer has definitely shifted toward” America” over the last three years. And lo and behold, America recently overtook China as , South Korea’s largest export market. GDP may be translated into clout within international economic organizations as well.

However, market exchange rate GDP comparisons do have some significant drawbacks. First of all, policy can be used to determine exchange rates rather than market fundamentals. The yuan and the dollar were once correlated in China. It now employs a “managed float,” which allows the exchange rate to fluctuate within a certain range set by the Chinese government. In practice,  , this can look sort of like a peg.

This implies that if China’s government made the decision to change the yuan’s trading range against the dollar, it might be able to suddenly make its economy appear larger than America’s in charts like those at the top of this post.

And it has the power to do so if China decides to lower its currency to encourage global exports. That will make its economy look smaller in nominal terms, but in fact it will improve China’s export competitiveness, so in some ways it means China’s economy is actually , stronger.

More fundamentally, exchange rates don’t affect real living standards. Despite all the reports about trade imbalances and other issues, the majority of what Chinese people buy is produced in China, and the majority of what Americans buy is produced there.

This includes rent, medical care, transportation, and so on. That implies that local prices will influence Chinese people’s material living standards significantly more than those of international ones.

PPP is an attempt to adjust for variations in local prices. International organizations like the World Bank conduct research in various nations to examine local prices of non-retail goods like rent and medical care. Then, they create a price index from which these are then derived. When comparing these price indices across nations, you can get a PPP conversion factor that they use to compare economies.

In theory, this gives a better comparison of how much , actual stuff , different countries produce. However, this approach has many practical flaws.

First of all, the teams sent by the World Bank and other organizations to check local prices won’t always receive a large sample of those prices. They might not look enough at small towns and too much at expensive cities like Shanghai. Or they might ignore the low price difference between regular apples in a boutique grocery store when purchasing expensive, premium apples.

On top of that, PPP is often out of date. Prices can fluctuate a lot, and the companies that conduct PPP surveys can’t conduct a thorough survey every year. This can lead to , big sudden revisions , that change our understanding of the past as well as the present.

As if that weren’t enough, PPP also has a hard time comparing quality between different countries ‘ goods and services. People who conduct surveys for the World Bank may not realize that a haircut in Japan might be superior to a haircut in America, but it might be. 1 ,

That quality difference should make Japan’s GDP ( PPP ) a little higher relative to America’s, but in practice, the statistics will often miss it. This is particularly crucial when it comes to the high-end medical care and housing stock.

Finally, because people buy different things in different countries, overall prices are difficult to compare. People in one nation might spend more on housing and less on health care than people in another. Do they do that because their primary concern is the cost of health care there, or because they simply want more of it? It’s hard to say.

All of these measurement issues lead to , big discrepancies , between countries ‘ own internal growth numbers and changes in the international PPP comparisons. And they cause a general ambiguity regarding how much we should trust PPP figures. When I cite PPP comparisons, someone often pops up in the comment section or the X replies to say “PPP is garbage”!.

That’s wrong — PPP is , not , garbage, it’s just hard to measure. But when you’re comparing individual living standards — that is, per capita GDP— there’s really just no alternative. You have no choice but to use PPP if you want to find out how wealthy people in China, America, or France actually are. This is because how much actual stuff a person can buy depends much more on local prices than exchange rates.

When it comes to comparing , national power and importance, though, it’s not clear PPP is the right measure either. The price of haircuts isn’t always a factor in the rise and fall of great powers.

But lots of things that are purchased domestically rather than traded on world markets are  , very , important for national power — for example, the salaries of soldiers, locally sourced armaments, local logistics costs, and so on. So if you want to look at military strength, you can’t really use market exchange rates either.

For this reason, some people attempt to create a “military PPP” that explicitly accounts for military expenditures. These numbers show, for example, that China’s military spending is , much closer to America ‘s , in size than official dollar numbers reflect.

However, national power is largely determined by factors other than armies alone. For instance, many of the civilian consumer goods produced could be turned into military products in the event of a major war, just like it was in America and many other nations in World War 2. Therefore, you can’t just look at defense spending when you want to learn about military capacity; you must also take into account all the dual-use items.

Earlier this year, Han Feizi , used this sort of comparison , to argue that China’s economy is already much bigger than America’s:

China’s PPP GDP is only 25 % larger than that of the US? Come on people… who are we kidding? China produced 2x as much electricity as the US last year, and it produced 12.6 times as much steel and 22 times as much cement. China’s shipyards accounted for over 50 % of the world’s output while US production was negligible. In 2023, China produced 30.2 million vehicles, almost three times more than the 10.6 million made in the US…On the demand side, 26 million vehicles were sold in China last year, 68 % more than the 15.5 million sold in the US. Chinese consumers bought 434 million smartphones, three times the 144 million sold in the US. China consumes eight times as much seafood and twice as much meat as the US as a nation.

A recent post , by the blogger” Austrian China” makes a number of other such comparisons — all of which are in China’s favor.

The claim here   is pretty bad when it comes to measuring living standards because it doesn’t account for true economic output and that comparisons should focus primarily on physical goods.

It makes no sense to just leave these out of international comparisons and concentrate only on electricity, cars, and ships because they are incredibly important determinants of how pleasant a life citizens of different countries lead.

But if you’re comparing , national power, this sort of argument might make a , lot , of sense. When a foreign empire’s bombs are pouring down on your cities and foreign missiles are sending your country’s fleet to the bottom of the sea, having nice housing, good medical care, or high-quality insurance services won’t help you much.

Fundamentally speaking, this is why I believe Americans should find it hard to believe that their GDP at market exchange rates is higher than China’s. With the world looking , more dangerous and warlike , by the day, manufacturing is a competition that the US and its allies can ill afford to lose.

Yes, China boosters like Han Feizi and” Austrians” who care only about physical goods are overconfident about the supremacy of the world’s sole manufacturing superpower. But in my judgment, taking comfort in America’s higher nominal GDP numbers is even more dangerously complacent.

Note:

1 I can assure you that the World Bank researchers are not known for their fashionable haircuts with reasonable assurance.

This , article , was first published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack and is republished with kind permission. Become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.