Just over a week ago, India’s federal home minister Amit Shah announced a plan to fence the open border with neighbouring Myanmar.

He said India would secure the rugged 1,643km (1,020-mile) boundary the same way in which “we have fenced the country’s border with Bangladesh”, which is more than twice as long.

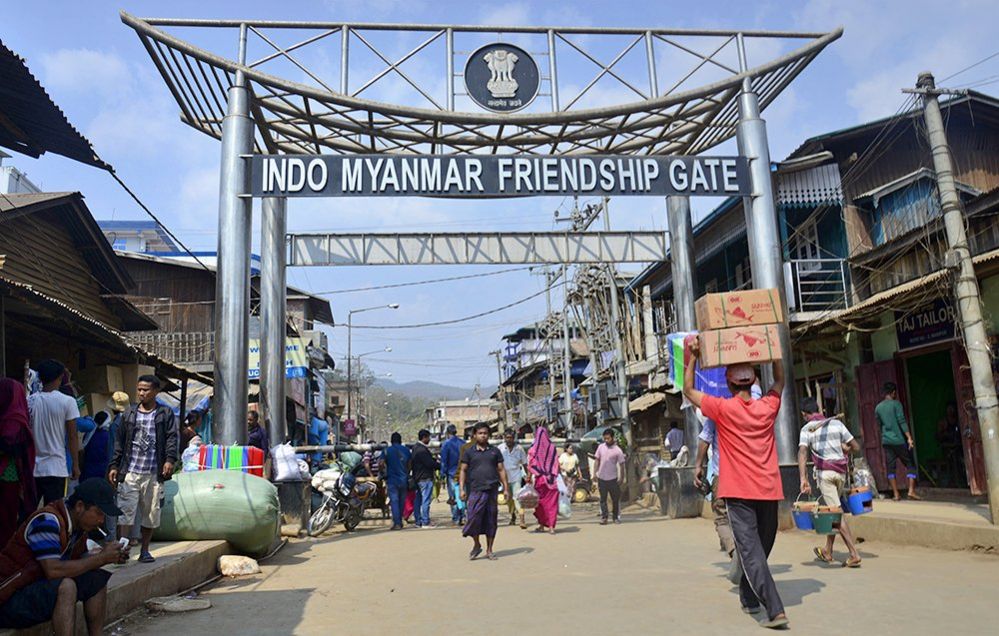

Mr Shah said the government would also consider scrapping a six-year-old free movement agreement, allowing border residents from India and Myanmar to travel 16km into each other’s territory without a visa. He gave few details of how the fence would be built, or over what timeframe.

But the move would be fraught with challenges – some experts say the mountainous terrain makes a fence all but impossible. And India’s plans could destabilise the equilibrium that has existed for decades between peoples in the border area, as well as stirring up tensions with its neighbours.

The move to fence the border – involving the four north-eastern Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram – appears to have come against the backdrop of two major developments.

First, the escalation of the conflict in Myanmar since the military coup in February 2021 posed a mounting risk to Indian interests. Some two million people have been displaced in the fighting, according to the UN. In recent weeks, ethnic rebels claimed to have taken over the crucial town of Paletwa in Chin state, disrupting a key route from Myanmar to India.

Second, ethnic violence sparked by an affirmative action row erupted last year in Manipur, which shares a near-400km border with Myanmar. Clashes between members of the majority Meitei and tribal Kuki minority have claimed more than 170 lives and displaced tens of thousands of people.

The government in Manipur, led by Indian PM Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has spoken about a “large number of illegal migrants” and said the “violence was fuelled by influential illegal poppy cultivators and drug lords from Myanmar settling in Manipur”.

Last July, India’s Foreign Minister S Jaishankar informed his counterpart Than Swe from Myanmar’s military-led government that India’s border areas “were seriously disturbed“. He said that “any actions that aggravate the [border] situation should be avoided”, and raised concerns about “human and drug trafficking”.

Michael Kugelman of the Wilson Center, an American think-tank, believes the move to fence the border is “driven by India’s perception of a growing two-pronged security threat on its eastern border”.

“It wants to limit the spill-over effects of a deepening conflict in Myanmar, and to reduce the risk of refugees entering an increasingly volatile Manipur from Myanmar,” Mr Kugelman told the BBC.

Some question the validity of this reason. While Manipur’s government has attributed the conflict there to an influx of Kuki refugees from Myanmar, its own panel had identified only 2,187 immigrants from Myanmar in the state by the end of April last year.

“This narrative of massive illegal immigration from Myanmar is false. This is being done to support the narrative that Kukis are ‘foreigners’ and illegal migrants, that they don’t belong to Manipur, and lately, that their resistance is getting support from Myanmar,” said Gautam Mukhopadhaya, a former ambassador of India to Myanmar.

“The logic and evidence for this is very thin. Kukis have inhabited Manipur for ages. The free movement regime has been working well for all communities including Meiteis who have benefitted from it commercially.”

A senior retired army officer, with experience in the region and preferring to remain unnamed, said the necessity for border fencing was not due to civilian migration but because several Indian rebel groups from the north-east had established camps in Myanmar’s border villages and towns.

For decades India’s north-east has been roiled by separatist insurgencies. The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), a law granting security forces search-and-seizure powers and protecting soldiers involved in civilian casualties during operations, has proven to be controversial. Indian rebels hiding in Myanmar can easily cross the border and “do their extortion and violent activities”, the officer said.

However, the move to fence the border is likely to meet resistance.

India and Myanmar have historic religious, linguistic and ethnic ties – some two million people of Indian origin live in Myanmar, which seeks greater economic integration through India’s Look East policy.

Under this policy, India has provided more than $2bn in development assistance – roads, higher education, restoration of damaged pagodas – to Myanmar, most of it in the form of grants.

More importantly, the border splits people with shared ethnicity and culture. Mizos in Mizoram and Chins in Myanmar are ethnic cousins, with cross-border connections, especially as the predominantly Christian Chin State borders Mizoram. There are Nagas on both sides of the border, with many from Myanmar pursuing higher education in India. Hunters from Walong in Arunachal Pradesh have come and gone across the border for centuries.

Not surprisingly, Mizoram, defying federal government directives, has sheltered more than 40,000 refugees who have fled the civil war in Myanmar. Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio, an ally of the BJP, said recently: “We have to work out a formula on how to solve the issue for the people and prevent infiltration as well, because Nagaland is bordered by Myanmar, and on both sides there are Nagas.”

Also, experts believe that fencing the mountainous and densely forested border will pose significant challenges.

“To fence off the entire border would be impossible given all the mountains along the border and the remoteness of the terrain. It won’t be like building a fence along the border with Bangladesh,” Bertil Linter, a well-known Myanmar expert, told me.

“A fence is impractical, would take years to build and even if is was built at some places, local people would find ways around it.”.

Then there’s the delicate diplomatic question. Constructing a border fence could be a provocative move at a time when Delhi needs to exercise caution in its interactions with Myanmar, according to Mr Kugelman. “India seeks junta support for border security and infrastructure development, among other priorities. Erecting the fence in consultation with Myanmar as opposed to pursing the project unilaterally would lessen the risk of tensions,” he said.

Ultimately, the move underscores India’s border security challenges – the country endures border tensions with arch-rival Pakistan and China – stemming from political tensions, territorial disputes, war, terrorism, or a combination of these factors. India is also pushing back against China in South Asia – and China has stronger economic connections with Myanmar compared to India.

“With India working to strengthen ties with its regional neighbours, and looking to fend off challenges from an increasingly present Beijing in its broader backyard, border challenges are an unwelcome intrusion. But they can’t simply be wished away,” said Mr Kugelman.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: