It is newsworthy on its own that conservative South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol flew to Tokyo to meet with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio last week.

Yoon’s predecessor, the progressive Moon Jae-in, demonstrated little interest in official meetings with his Japanese counterparts across his five years as president, one of the few things he had in common with his conservative forebear Park Geun-hye.

Park, whose political opponents were quick to dismiss her as the daughter of a Japanese-trained military strongman, also avoided meetings with Shinzo Abe without an American mediator present. Instead, she focused her efforts on Chinese leader Xi Jinping, in the vain hope that he would play a proactive role in inter-Korean reconciliation.

As the PRC’s bilateral trade with South Korea has come to dwarf exchanges between South Korea and Japan, so have its diplomatic interactions with Seoul’s leadership compared with Japan’s.

For those concerned about regional security, especially North Korea’s growing nuclear and missile arsenals and, increasingly, the PRC’s revisionist aims for the Indo-Pacific, the tensions between Japan and South Korea have long been a source of frustration.

Their lack of cooperation hinders intelligence sharing and prevents a united front against malign North Korean and PRC actions, as Pyongyang and Beijing know they can use historical issues to drive a wedge between Washington’s two Northeast Asian allies.

Yet bad security policy has proven to be good politics in both countries. It’s only with recent developments — Beijing’s sanctions against South Korea over missile defense, its lack of transparency over Covid, its acts of cultural chauvinism at Korea’s expense — that South Koreans’ assessments of the PRC began to sink even lower than their views of Japan.

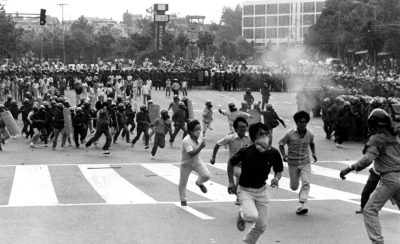

Even that shift is a phenomenon largely attributable to the younger generations in Korea, particularly 20- and 30-somethings who do not remember their country’s period of military dictatorship, spearheaded as it was by individuals who drew inspiration from Japan’s Meiji Restoration and who took aid from Japan in exchange for normalization.

The earlier generation that resisted the military dictatorship, however, has generally been skeptical of deals with Japan — going all the way back to the 1965 normalization treaty— and its members remain disproportionately influential in Korean politics.

Add to that the fact even the younger, more anti-PRC generation isn’t particularly pro-Japan (as reactions to Yoon’s recent moves have revealed) – and the additional fact that Japanese politicians aren’t above downplaying their country’s historical record and pressing claims to territory South Korea administers – and it becomes clear why closer security ties between the two have remained a fantasy confined to the imaginations of American diplomats and generals.

At least, that’s what we thought. In recent weeks, Yoon’s government has announced a deal with Japan over the contentious issue of wartime forced labor. This resulted in enthusiastic — perhaps excessively so — reactions from partners of the two countries, including the United States.

Then Yoon traveled to Tokyo — the first summit between Korean and Japanese heads of state in 12 years — and toasted with Kishida. Then Japan announced that it would lift its export restrictions on South Korea, a major step (albeit one confirming that the restrictions, announced in 2019 as tensions over the historical issue of wartime labor began rising, were always politically motivated).

That these are serious steps toward rapprochement is beyond question. What is more debatable is how long-lasting they will be. Yoon’s steps have already been denounced by the Japan skeptics in the opposition party, who still have an overwhelming majority in the National Assembly.

As noted above, even the younger generation that distrusts the PRC does not support Yoon’s forced-labor deal. Comparisons are already being made to the 2015 US-brokered deal in which Tokyo compensated the “comfort women” — wartime victims of Imperial Japanese sexual slavery — as a deal conservatives have struck without the majority support of the public, a deal that a progressive successor administration could undo easily.

After all, the tensions with Japan that defined Moon’s administration did not begin with the forced-labor issue or with Japan’s export whitelist but escalated before that when Moon annulled the comfort women deal.

The maverick Yoon, however, has some advantages that Park Geun-hye did not. He is not beholden to the legacy of the Park family — as head of the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office, his most famous case was probably Park herself — nor to the legacy of Japanese colonization. His popularity, while never particularly high, may have already reached its nadir in late 2022.

Yoon is also, unlike Park in 2015, less than a year into his presidency, with much time left for this supposed “betrayal” to fade from voters’ minds. Yoon, although less confrontational toward Beijing than some in the Anglosphere had hoped, is still far less accommodating of the PRC than Moon (or Park) and might yet cause a sharp shift in Northeast Asian security dynamics by moving closer to Tokyo.

The results, however, are not entirely up to him.

If Seoul’s partners and allies, concerned about the PRC’s and North Korea’s intentions for the region, want to see a South Korea that’s more active in the region, they need to encourage more activity following this development. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue should, if it’s not going to make the country a fifth member, deepen and normalize its cooperation with Seoul, either by itself or in a Quad-plus format with other partners.

Japan, which has not always encouraged South Korean participation in international forums such as the G7, should support Seoul as it seeks to embrace its “middle power” status – including increased engagement with ASEAN and the Pacific Islands, places where America’s partners are essential to US efforts to counter PRC influence.

Not to encourage Japan’s leadership to resort to censorship, but it ill behooves Tokyo’s efforts to strengthen bilateral ties for domestic politicians and political movements to fan anti-Korean sentiment and receive little pushback.

The United States can also play a role that extends beyond words of affirmation — and can do so by taking some long-overdue steps.

Both Korean and Japanese manufacturers have cried foul over 2022 US Congressional legislation that seeks to reshore American manufacturing but has had the side effect of nullifying tax credits and subsidies for foreign manufacturers – even those that, like Korean and Japanese companies, seek to build on the US mainland. Such manufacturers should have been rewarded regardless of Korea-Japan ties.

A time when bilateral relations are improving is as good a time as any to take such a step. Now would also be a good time to take steps toward a unified plan of action making countries, such as South Korea, less vulnerable to Beijing’s economic coercion.

Any deal between South Korea and Japan is likelier to endure the more Koreans see it as benefitting them. Yoon, whatever else one thinks of him, is taking a bold step in defiance of precedent and public opinion. He should not be the only one taking such steps.

Rob York ([email protected]) is the director for regional affairs at Pacific Forum and editor of Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific.

This article was first published by Pacific Forum and is republished with permission.