By Flora Drury, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen it comes to planning a vacation, Afghanistan is not at the bottom of most people’s must-visit names.

Decades of conflict mean that few tourists dared step foot in the Central Asian nation since its heyday as part of the hippie trail in the 1970s. And the future of whatever tourism industry had survived was thrust into further uncertainty by the Taliban’s return to power in 2021.

However, a quick search through social media indicates that not only has commerce flourished, but it has also survived in its own, incredibly market way.

” Five reasons why Afghanistan should become your second trip”, gush the happy celebrities, their devices sweeping across glistening lakes, through rocky runs and into colouful, busy areas.

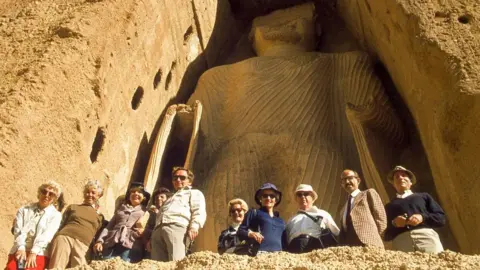

Others claim that Afghanistan has n’t been this safe in 20 years, posing as a threat to the enormous divide left by the Bamiyan Buddha’s destruction more than 20 years ago.

Behind the sunny claims and glamorous videos are questions about the risks these travellers are taking, and exactly who this burgeoning industry is truly helping.

A government eager to change the tale in its favor, or a inhabitants struggling to survive?

Dr. Farkhondeh Akbari, whose household fled Afghanistan during the first Taliban government in the 1990s, refers to those video on TikTok where a Taliban manual and Taliban official give tourists tickets to the site of the destruction of the Buddhas.

” These are the people who destroyed the Buddhas”.

‘ It’s only raw’

On first hearing, Sascha Heeney’s travel plans do n’t seem like ideal vacation spots; instead, they’re places that many people are more familiar with reading about in the news.

But finally, that appears to be precisely why Heeney, and thousands more like her across the globe, picked them out: off the beaten track, as far apart from a five-star location as you can get- and so, almost completely unique.

So perhaps it is not surprising she was won over by Afghanistan.

” It is just raw”, says the part-time go guide from Brighton, UK. ” You do n’t get much rawer than there. That might be interesting if you want to witness genuine life.

But what do the Taliban leave? After all, they have a reputation for being greatly suspicious, angry also, towards outsiders, especially Westerners.

And yet here they are, posing, if slightly uncomfortable, alongside the tourists, with guns on display, and their hairy faces about to go viral on TikTok ( banned in the country since 2022 ).

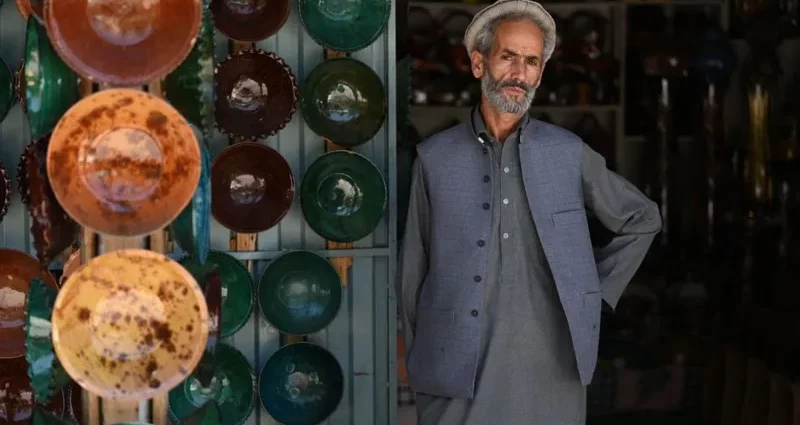

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt one level, the answer is easy. The Taliban- generally isolated abroad, under popular sanctions and prevented from accessing funds given to Afghanistan’s past government- need money.

The tourists – whose numbers have crept up from just 691 in 2021 to more than 7,000 last year, according to AP news agency – bring it.

Most seem to join one of myriad tours offered by international companies, providing a peek at the “real Afghanistan” for a few thousand dollars a trip.

Mohammad Saeed, the head of the Taliban government’s Tourism Directorate in Kabul, said earlier this year that he dreamed of the country becoming a tourist hotspot. In particular, he revealed, he was eyeing up the Chinese market- all with the backing” of the Elders”.

” With tourism, everything they want to do is good,” says Afghan tour guide Rohullah, whose gleeful expression has been shared countless times by appreciative clients since he started leading groups three years ago.

” Tourism creates a lot of jobs and opportunities”, he adds– and he should know.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe received a job as a tour guide from a friend in 2021, when the Taliban seized power as the US pulled out of the country. He refers to this as” the change.” He had previously worked for the Afghan finance ministry for eight years.

And he has n’t regretted it. There is no shortage of work for tour groups like Sascha Heeney’s, and local guides and drivers are needed.

Then, it should come as no surprise that there are groups of men, all of whom are men, taking classes in Kabul’s Taliban-approved hospitality industry in an effort to profit from the burgeoning industry.

” We expect much for this year”, Rohullah says. ” This is a peaceful time- it was not possible to travel to all parts of Afghanistan before, but for now, it really is possible”.

The killing of three Spanish tourists and an Afghan at a market in Bamiyan in May by the Islamic State-affiliated ISK militant group stood out for being unusual because it targeted foreigners.

The British Foreign Office continues to advise against all travel to the country, which remains a target for attacks. ISK carried out 45 in 2023 alone, according to the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

Of course, a large portion of Afghanistan’s increased security is due to the fact that the Taliban were directly responsible for the majority of the violence during the 20-year conflict that swept over the nation following the US invasion.

Take- for example- the first three months of 2021, when the UN attributed more than 40 % of the 1, 783 civilian casualties recorded to the Taliban. It was n’t just the Taliban though. According to the same report, 25 % of the same-time casualties were caused by US-led Afghan government forces.

” Learn the game and know the rules”

What is perhaps more surprising is that Heeney and two other members of the group she led for Lupine Tours earlier this year were women, and they were not the only ones. Even though Young Pioneer Tours only offers female trips to Afghanistan, it has a long history of organizing trips to North Korea and other off-grid locations. Without any issues, Rohullah has accompanied female solo travelers.

The Taliban’s strict regulations for their own female population, which have resulted in them being forced out of the workforce, out of secondary education, and even out of Band-e-Amir national park, a stop on many of the available international tours, do not prevent female visitors.

But it does mean that “women and men have different encounters” in Afghanistan, acknowledges Rowan Beard, who has been bringing groups to Afghanistan since 2016. It is not necessarily a bad thing, he argues.

” Men cannot speak with women, women can”, he explains. Our female tourists had the opportunity to sit with a group of women and hear from them about their experiences and additional insights into the nation.

However, everyone must adhere to the regulations in place. Before those rules were in place, Sabha Heeney and her group were given information on what they should do, including what they should wear, how to act, and who they could and could not talk to.

The Taliban, who were constantly present and using their guns to watch from the sidelines, were among those who refused to speak with Sascha or the women who made up her group. But she did n’t begrudge it.

” You have to kind of know the rules and learn the game”, she explains.

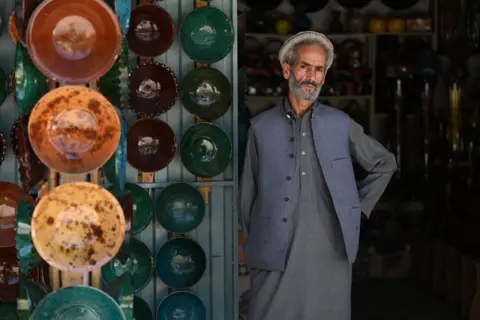

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTalking with the women, who were “incredibly happy,” was Heeney’s highlight on a trip where Afghanistan’s “absolutely lovely”, generous, and welcoming people stood out.

However, the women are noticeably absent from vibrant street scenes in the videos posted on social media, which one visitor glossed over, saying that they are just doing what women around the world enjoy doing: shopping.

Whitewashing our suffering, in my opinion.

Watching these slick videos from outside Afghanistan, some are left with a bitter taste.

“]Tourists think ] it is just this backward part of the world, and they can do whatever they want- we do n’t care”, says Dr Akbari, now a postdoctoral researcher at Monash University in Australia.

” We just go out and enjoy the landscape, and we’ll get our opinions and likes.” And we are deeply affected by this.

She goes on to say that it is “unethical tourism with a lack of political and social awareness,” which makes the Taliban cover up the realities of life now that they are back in power.

Because this is, arguably, the other value of tourism to the Taliban: a new image. one that does n’t focus on the laws that govern Afghan women’s lives.

AFP

AFPDr. Akbari makes the observation that “my family- they have no male guardian- cannot travel from one district to another district.” ” We are talking about a regime that has implemented gender apartheid,” according to the statement “50 % of the population has no rights.”

” And yes, there is a humanitarian crisis: I’m happy that tourists might shop at a store and purchase goods to help a local family, but what is the price? It is normalising the Taliban regime.”

Sascha Heeney admits to having a “moral struggle” before her visit with the Taliban regarding women.

” Of course, I feel very strongly about their rights- it crossed my mind,” she says”. However, as a traveler, I believe that our culture has a skewed perspective. I enjoy using my own eyes to see. I can make my own judgment.”

Beard argues for letting people” make their own conclusions rather than there being a one-size-fits-all answer to the experience women have in the country”.

However, according to Mariana Novelli, a professor of marketing and tourism at Nottingham University School of Business, some social media users ‘ overly positive views can be seen as problematic.

” I would be very wary of the sensationalisation of a destination,” she says, explaining that some may” paint an image that is naïve”.

” Sometimes travellers also want to send a positive message- but that does not mean that problems ]are n’t still there].”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut boycotting is also not the way forward, argues Prof Novelli, who sits on an international tourism ethics board.

That is problematic for me because it isolates these nations even more.

There are plenty of tourist destinations in the world north with governments with questionable practices, she says, which raises a question of where to draw the line.

But then, the potential for benefit is also worth considering: in Saudi Arabia, she says, a growing tourism industry has led to a widening role in society for women.

” I think tourism can be a force for peace, for cross-cultural exchange,” Prof Novelli says.

However, that potential does not make women like Dr. Akbari, her family, and friends in Afghanistan, easier.

” Our pains and our sufferings are being whitewashed,” she says”, brushed with these fake strokes of security the Taliban want.”