As the film “Oppenheimer” arrives in American theaters, it is important to take a fresh look at the race to produce the atomic bomb and the choice of Hiroshima as its first target. There’s a lot more to learn that isn’t in the movie.

Hiroshima was struck by an 11-kiloton atomic bomb that had never been previously tested. But the task to destroy Hiroshima was critical in stopping Japan’s atomic bomb program and either forcing Japan’s surrender or, if Japan did not surrender, protecting the huge planned US and allied amphibious attack on Japan.

I want to emphasize what you are reading is my own analysis of why Hiroshima was a critical, top priority target enabling the allied invasion of the Japanese mainland. It differs greatly from US explanations, which (when taken on balance) are nonsensical.

If Hiroshima was a civilian target selected by the US government, then it was a war crime to carry out the attack. If it was a strategic, military target, then the attack on the city was justifiable.

It is important to note that the US government was, during and after the war and until today, covering up the real truth about the atomic bomb threats of Germany and Japan. Indeed, General Douglas MacArthur, who ran the US occupation of Japan after the surrender, systematically covered up Japan’s atomic bomb program and Japan’s biological and chemical weapons program in China.

Even today questions are still asked why Hiroshima was chosen? Why did the United States not demonstrate the atomic bomb before actually using it on a Japanese city, followed by dropping a Plutonium-fueled bomb that was used against the Japanese city of Nagasaki.

After the Hiroshima blast, Japan’s top atomic scientists flew to Hiroshima, headed by Yoshio Nishina from the RIKEN institute. Japan was desperately short of aircraft but Nishina and his team of scientists were given top priority.

Japan had two atomic bomb programs, one under the aegis of the army centered at RIKEN called Ni-Go and the other, under the navy, known as the F-Go program, headed by Professor Bunsaku Arakatsu. Late in the war the navy program was far along. The bombs were to be assembled in Korea. Korea had become Japan’s main arsenal supplying the war effort.

Japan’s top scientists quickly figured out that the bomb that struck Hiroshima was an atomic weapon. They measured residual radiation with Geiger counters. By assessing the blast patterns on the sides of partly standing buildings, they understood that the bomb was detonated above ground giving it maximum coverage over the target.

Hiroshima was destroyed by a uranium bomb called Little Boy. Testing it was not possible because there was not enough enriched uranium (U-235). Yet there was much greater confidence that the uranium bomb would work and was less complex than the plutonium implosion device, known as Fat Man, dropped a few days later on Nagasaki.

One of the big secrets of World War II is that both Germany and Japan were far along on atomic weapons development. For political reasons, the US did not want the American population to know just how dangerous atomic bomb development was to the soldiers fighting in Europe and in Asia.

Had the Germans been able to set off an atomic blast during the Battle of the Bulge, US and British forces would have been wiped out. Had Japan unleashed an atomic bomb on the US fleet, the US invasion force would have been destroyed.

Japan even had plans to launch an aircraft from a submarine carrying an atomic bomb. Japan was planning to destroy San Francisco and force the United States into peace negotiations favorable to Japan. Japan’s backup plan was to hit San Francisco with biological weapons launched by the same aircraft.

A very controversial book published in Germany in 2005 (Hitler’s Bomb, by Rainer Karlsch) claims that the Nazi regime set off a crude nuclear device at the military testing ground at Ohrdruf in southern Germany, then housing thousands of concentration camp inmates who became the bomb’s victims.

The US also was aware that Germany was working on long range bombers that could attack New York or Washington, DC. Called the Amerikabomber by the Germans, four different prototypes were built by different German aerospace companies (Messerschmidt, Junkers, Focke-Wulf, Heinkel, Horten Brothers), but none went into serial production. During the war, American cities either turned off the lights or used blackout curtains, fearing a Nazi air attack.

Since the war, there has been a lot of mythology that the Germans were not that far along on a bomb and that Japan was even farther behind. The US-British Alsos Mission, headed by Boris Pash, which sent US and British scientists to Europe and Japan, reported that while both countries were working on atomic bombs, they were not even close to having them.

In my opinion the Alsos reports were deliberately misleading. They never accounted for alleged atomic tests in Germany and in Korea, then considered part of Japan. (All of Korea had been annexed by Japan in 1910.)

I suggest the following proposition: Oppenheimer never agonized over the use of the atomic bomb on Japan. He made a show of agonizing after his clearances were suspended, but he did so mostly after all the critical decisions on the use of the bomb had been made. He strongly supported the decision to use the atomic bomb on Japan.

One clear proof: 155 Manhattan project atomic scientists in 1945 pushed for a demonstration of the bomb to convince Japan of the mortal danger they faced. The petition written by Leo Szilard was sent to Oppenheimer in hopes he would sign it. He did not. Oppenheimer told Edward Teller that scientists had no place involving themselves in policy decisions. The petition was also sent to General Leslie Groves and others. It was supposed to be delivered to President Truman but Groves and others made sure that it was not.

The Houtermans warning

Fritz Houtermans was a leading atomic physicist who during the war was in Germany. He was regarded as a maverick but he was supported by key German scientists who bailed him out from a Gestapo jail (and tried, before that, to get him out of an NKVD jail in Russia). Houtermans never made any secret of the fact he was a communist.

Houtermans created the physical foundations for the development of a hydrogen bomb. He prepared a secret report in 1941 on the question of the initiation of a nuclear chain reaction, which was dispatched to important German nuclear physicists. In that 1941 treatise Houtermans predicted the possibility of plutonium fission and set out potential implications.

This put Houtermans well ahead of the storied Manhattan Project (the US atomic bomb program was officially conducted under the leadership of the so-called Manhattan Engineering Program, just as the British atomic bomb program was called the Tubes Alloy program). The US atomic program did not get started until 1942.

The background of the Manhattan Project was a letter to President Roosevelt signed by Albert Einstein. The letter was drafted for Einstein by physicists Leo Szilard, Eugene Wigner and Edward Teller. That letter, now justifiably famous, informed Roosevelt about the danger of an atomic bomb. Einstein signed the final typed version on August 2, 1939. Szilard, Wigner and Teller all hailed from Hungary. Houtermans called them the “men from Mars.”

In fact, the record showed that Houtermans in 1940 discussed his research findings with top German scientists. Houtermans was an important member of the German Uranverein (the Uranium Club or Project) and worked with Manfred Von Ardenne on plutonium chain reactions. After the war, Von Ardenne would go to the Soviet Union, where he helped the Russians develop their atomic weapons.

But Houtermans did more than work as a physicist. He was permitted to travel to a scientific meeting in Switzerland during the war. From there Houtermans sent a telegram to Eugene Wigner at the Met Lab in Chicago. The Met Lab was the home of the first atomic reactor (then called an atomic pile), which paved the way for the production of plutonium. The cable said, “Hurry Up, We are on the track.”

Houtermans was well informed about developments in the United States, probably because the Nazis were spying on the Soviets who were spying on the Manhattan program.

Convergence of atomic scientists

The atomic scientists in the US and British programs in many cases were already refugees from the Nazi persecution of Jews in Europe who were closely connected to non-Jewish scientists who ended up working on the Nazi program. Even some of the scientists who were not Jewish – for example Enrico Fermi, whose wife, Laura Capon, was Jewish – needed to escape the racial laws being applied in Italy by the Mussolini fascist government.

A similar fate applied to communists. Even though Fritz Houtermans was an active communist before the war, he was able to be saved by his well-placed German friends.

Houtermans, of course, knew the scientists who left Germany and other European capitals under Nazi control. These scientists escaped the grip of the Nazis either because of their religious backgrounds or their political opposition to the Nazis or if their previous association with communist organizations.

Houtermans was not Jewish but his mother was, and under Jewish halachic law and German racial laws he would have been counted as a Jew. He never hid his Jewish background. When he was taunted for being Jewish he would reply, “When your ancestors were still living in the trees mine were already forging checks.”

There is another fascinating tie-in to Oppenheimer. Both Oppenheimer and Houtermans were in love with a woman named Charlotte Riefenstahl. She was a physicist who received her doctorate in 1927, the same year as Oppenheimer and Houtermans. She married Houtermans and was his first wife and third wife. (Counting her twice, Houtermans was married four times.)

Why Hiroshima? Enrichment!

Oppenheimer strongly supported the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. While later in life he suggested that the atomic bombing helped save American lives, he also confessed to the problem of conscience about using such a terrible weapon.

It is possible this remorse had much to do with his opposition to the hydrogen bomb, a bomb that Edward Teller called the “Super.” In place of the Super, Oppenheimer pushed for a larger number of small, tactical nuclear weapons.

Even so, he quickly made many enemies in official Washington, including Lewis Strauss, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, who pushed to declare Oppenheimer disloyal, in part because of his ties to known communists and in part due to Oppenheimer’s opposition to the Super. Oppenheimer would lose that battle and his security clearances would be revoked.

The question of bombing Hiroshima still is with us today. Why would the US attack a peaceful city that was not a major hub of military activity when, instead, the US could have used the bomb against concentrations of Japanese military forces?

President Harry Truman said that Hiroshima was a military target. That Truman statement has echoed down through the years, since most historians argue that Hiroshima was not a military target and Hiroshima was never a target for US bombers during the war.

Truman, once he became President, was getting a full intelligence dump on the war in Japan. (During his time as Vice President he had not known about the US atomic bomb program.)

The US was preparing for a major invasion of the largest Japanese island of Honshu, the location of Tokyo and the home of Japan’s emperor. This required a massive invasion fleet, both to bombard Japan’s defense installations and to bring allied troops ashore. But if Japan had atomic weapons the fleet could be destroyed in a Japanese attack.

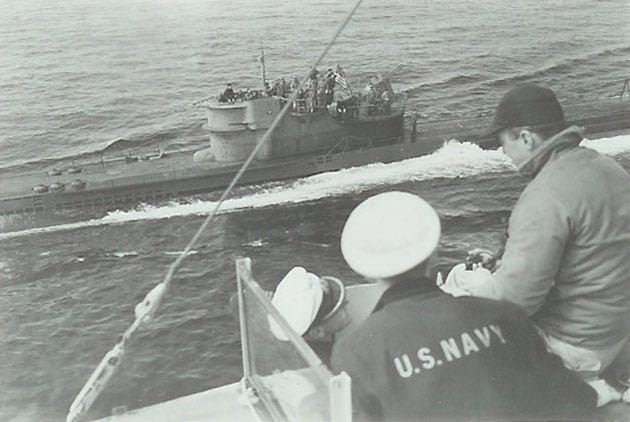

From around 1943 the United States was secretly working to stop Japan’s atomic weapons program. Part of that effort was to interdict Japanese (later Italian) submarines transporting enriched uranium to Japan from Germany. Wherever possible, Japanese and Italian submarines carrying uranium were attacked by the navy. Some of them were sunk; others were taken into custody.

Even after the European war ended, a German submarine configured for transport, U-234, surrendered to US ships off the coast of Nova Scotia. It was carrying uranium and, according to a German submarine crew-member witness, Robert Oppenheimer flew to Portsmouth where the sub had been taken. He examined the cargo and had its uranium contents, 560 kg, sent to Washington and then on to Oak Ridge, where Ernest Lawrence’s calutrons were enriching uranium for bomb making. A calutron is a specialized type of cyclotron developed at Lawrence’s Berkely California laboratory

At Oak Ridge there were two calutron systems. The first, known as the Racetrack, was a series of linked calutrons that did the initial uranium enrichment, tapping out at 20% enrichment. The second group of B-series calutrons took the product scraped from the Racetrack and removed impurities, bringing the level of enrichment to 90%, the level needed for a uranium-fueled atomic bomb.

Around 100kg of 90% enriched uranium is enough for an atomic bomb.

US officials have always said that the Japanese submarines were transporting uranium oxide, not enriched uranium. But there would have been no need to ship uranium oxide to Oak Ridge unless it could be fed into Lawrence’s calutrons.

Japan had no need for unrefined uranium. Korea had plenty of uranium ore and Japan had built specialized facilities for bomb making at Konan (then known as Hamhong). The material on U-234 was uranium metal and was partially enriched. Japan had the capability of further enrichment, most likely using advanced centrifuges built by Sumitomo. The centrifuges have never been found. Neither has the other infrastructure for enriching uranium been found.

The uranium material on U-234 was in special radiation-protected containers stored in the outer hull of the submarine so as not to endanger the crew. Each of the containers had “U-235” painted on it by two senior Japanese military officers who sailed on the submarine.

Allegedly before U-234 surrendered to the US Navy, the two Japanese officers committed suicide by taking poison, a very untraditional way of carrying out Seppuku. There were suicide notes to their families, written in German (probably because no member of the U-234 crew could write in Japanese, since the notes were clearly forgeries). They were buried at sea.

Truman and Oppenheimer may have realized that Japan’s uranium enrichment capability was centered at Hiroshima. One of the compelling reasons Nishina and his team hurried to Hiroshima was to find out if any of Japan’s uranium enrichment infrastructure survived.

From Hiroshima the final bomb grade U-235 was shipped to Korea, where more than half of Japan’s atomic weapons program was based.

David Snell’s reporting

In 1946 an enterprising reporter from the Atlanta Constitution, David Snell, based on a credible Japanese source, revealed that the Japanese had already tested two small atomic bombs, one in Mongolia and the other off the eastern coast of Korea. Called the Genzai Bakudan (Greatest Fighter), it was detonated on a small island in the Sea of Japan on August 12, 1945. Three weeks earlier, on July 16, 1945, the US tested the “Gadget” –a plutonium bomb. It is not clear that Japan knew about the Trinity test of the atomic bomb.

Snell’s article was denounced by US authorities. However, it was never disproven.

Destroying Hiroshima may have put an end to Japan’s nuclear bomb program by destroying its uranium enrichment infrastructure.

There is an entire literature about the US choice of targets and the somewhat “accidental” selection of Hiroshima. I would think that the story was partly fabricated to hide the real objective of eliminating Japan’s bomb making potential.

Oppenheimer, privy to the most sensitive atomic intelligence, a visitor to Portsmouth where U-235 was berthed, certainly acted on behalf of the nation in using the atomic bomb to eradicate a real threat. There was no need to feel guilty over it.

Stephen Bryen is a senior fellow at the Center for Security Policy and the Yorktown Institute. This article was originally published on Weapons and Strategy, his Substack. Asia Times is republishing it with permission.