BBC World Service

BBC

BBCA BBC Eye research has revealed that an American pharmaceutical company produces improperly high-intensity, very addicting opioids and exports them to West Africa, where they are causing a significant public health crisis in nations like Ghana, Nigeria, and CoteD’Ivoire.

Aveo Pharmaceuticals, based in Mumbai, makes a range of supplements that go under various brand labels and are packaged to appear like genuine treatments. But all contain the same dangerous combination of ingredients: fact, a prominent narcotic, and four, a body relax so addicting it’s banned in Europe.

This combination of medications has a worldwide ban on their use, and they can trigger seizures and breathing difficulties. An abuse can remove. Because they are so cheap and readily available, these opioids are common as street drugs in many East African countries, despite the risks.

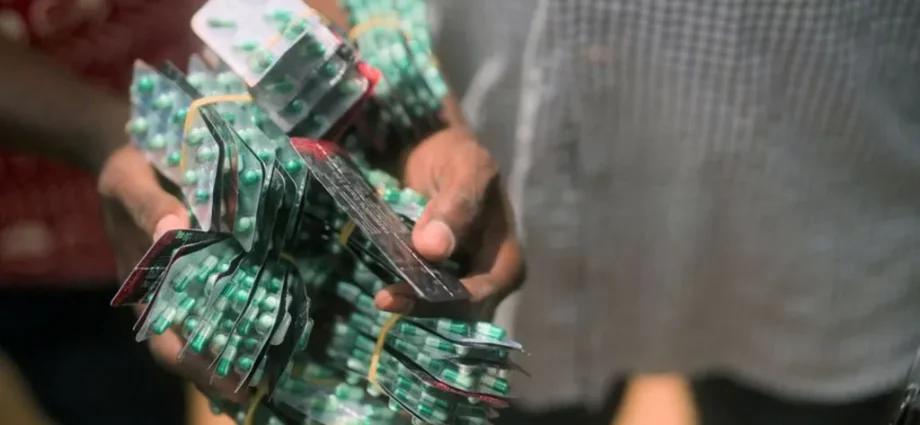

The BBC World Service found bits of them, branded with the Aveo symbol, for sale on the roads of Ghanaian, Nigerian, and Ivoirian towns and cities.

The BBC eluded detection of the drugs after finding them at Aveo’s factory in India and posing as an American businessman looking to offer opioids to Nigeria. Using a concealed cameras, the BBC filmed one of Aveo’s managers, Vinod Sharma, showing off the same hazardous materials the BBC found for sale across West Africa.

The official claims in the quietly captured video that Sharma’s intention is to sell the pills to Nigerian teenagers who” all adore this product.” Sharma doesn’t recoil. ” OK”, he replies, before explaining that if people take two or three medications at once, they may “relax” and agrees they may get “high”. Towards the end of the meeting, Sharma says:” This is very dangerous for the health”, adding “nowadays, this is company”.

It is a company that is destroying the potential of millions of North African younger people and putting them at risk.

One of the city’s leaders, Alhassan Maham, has set up a voluntary process pressure of about 100 local residents whose goal is to assault drug dealers and remove these pills from the streets of Tamale, in northeastern Ghana, because so many young people are taking illegal opioids.

According to Maham,” the medicines consume the sobriety of those who abuse them, like a fire fires when oil is poured on it.” One Tamale addiction put it even more succinctly. The pharmaceuticals, he said, have “wasted our lives”.

Following a tip off about a drug deal, the BBC group launched a assault in one of Tamale’s poorest communities and followed the work force as they boarded motorcycles. A young man was passing by him and appeared to have taken these medications, according to visitors.

When the seller was discovered, he was traveling with a plastic bag containing Tafrodol-labelled clean supplements. The boxes were stamped with the unique brand of Aveo Pharmaceuticals.

It’s not just in Tamale that Aveo’s medications are causing pain. The BBC found related products, made by Aveo, have been seized by authorities abroad in Ghana.

Additionally, we discovered proof that Aveo’s medications are for sale on the streets of Nigeria and Coted’Ivoire, where teenagers mix them with an adult energy drink to raise the great.

Publicly-available export data show that Aveo Pharmaceuticals, along with a sister company called Westfin International, is shipping millions of these tablets to Ghana and other West African countries.

Nigeria, with a population of 225 million people, provides the biggest market for these pills. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, it is estimated that about four million Nigerians use some form of opioid.

The Chairman of Nigeria’s Drug and Law Enforcement Agency ( NDLEA ), Brig Gen Mohammed Buba Marwa, told the BBC, opioids are “devastating our youths, our families, it’s in every community in Nigeria”.

Nigerian authorities attempted to control the widely used opioid painkiller called tramadol in 2018 following a BBC Africa Eye investigation into the sale of opioids as street drugs.

The government slapped a strict cap on the maximum dosage and slowed down imports of illegal pills, as well as outlawing the sale of tramadol without a prescription. Indian authorities also enacted stricter export controls for tramadol at the same time.

Not long after this crackdown, Aveo Pharmaceuticals began to export a new pill based on tapentadol, an even stronger opioid, mixed with the muscle-relaxant carisoprodol.

Officials in West Africa are putting a stop to the opioid exporters who appear to be using these new combination pills as a substitute for tramadol and to fend off the crackdown.

There were almost ceiling-high cartons of the combination drugs stacked on top of each other in the Aveo factory. On his desk, Vinod Sharma laid out packet after packet of the tapentadol-carisoprodol cocktail pills that the company markets under a range of names including Tafrodol, the most popular, as well as TimaKing and Super Royal-225.

He told the BBC’s undercover team that “scientists” working in his factory could combine different drugs to “make a new product”.

Watch India’s Opioid Kings from BBC Eye Investigations on iPlayer or, if you are outside the UK, watch on YouTube.

Even more dangerous is the new product from Aveo than the tramadol it replaced. Tapentadol “gives the effects of an opioid,” including very deep sleep, according to Dr. Lekhansh Shukla, assistant professor at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences in Bengaluru, India.

” It could be deep enough that people don’t breathe, and that leads to drug overdose”, he explained. ” And along with that, you are giving another agent, carisoprodol, which also gives very deep sleep, relaxation. It sounds like a very dangerous combination”.

Because it is addictive, carisoprodol has been banned in Europe. Although it is only for brief periods of up to three weeks, it is permitted to use in the US. Withdrawal symptoms include anxiety, insomnia, and hallucinations.

When mixed with tapentadol the withdrawal is even “more severe” compared to regular opioids, said Dr Shukla. ” It’s a fairly painful experience”.

He claimed that he was aware of no studies that evaluated the efficacy of this combination. Unlike tramadol, which is legal for use in limited doses, the tapentadol-carisoprodol cocktail “does not sound like a rational combination”, he said. This is not something that can be used under our laws.

Pharmaceutical companies in India are prohibited from producing and exporting unlicensed medications unless they comply with the laws of the importing nation. According to Ghana’s national Drug Enforcement Agency, this combination of tapentadol and carisoprodol is unlicensed and prohibited. Aveo ships Tafrodol and similar products there. By bringing Tafrodol to Ghana, Aveo is breaking Indian law.

We put these allegations to Vinod Sharma and Aveo Pharmaceuticals. They did not respond.

The CDSCO, the country’s drug regulator, informed us that the Indian government is committed to ensuring India has a responsible and effective pharmaceutical regulatory system.

Additionally, it stated that recent regulations are strictly enforced and that exports from India to other nations are closely monitored. Additionally, it urged importing nations to help India’s efforts by ensuring they had similarly strong regulatory frameworks.

The CDSCO stated that it has discussed the issue with other nations, including those in West Africa, and is working with them to stop wrongdoing. Any pharmaceutical companies found to be in breach of the regulator’s orders to immediately take action.

Not just one Indian company produces and exports unlicensed opioids, but also Aveo is one. According to publicly available export data, other pharma companies may produce comparable products, and drugs with different branding are widely available throughout West Africa.

These manufacturers are putting a damper on India’s rapidly expanding pharmaceutical sector, which produces high-quality generic medications that millions of people depend on worldwide and produces vaccines that have saved millions of lives. The industry’s exports are worth at least$ 28bn ( £22bn ) a year.

The BBC’s undercover agent, whose identity must be kept secret for his safety, discusses his meeting with Sharma, saying:” Nigerian journalists have been reporting on this opioid crisis for more than 20 years but finally, I was face to face with one of the men at the root of Africa’s opioid crisis, one of the men who actually makes this product and ships it into our countries by the container load. He knew the harm it was doing but he didn’t seem to care … describing it simply as business”.

Back in Tamale, Ghana, the BBC team followed the local task force on one final raid that turned up even more of Aveo’s Tafrodol. In a nearby park that evening, they gathered to burn the illegal substances they had seized.

” We are burning it in an open glare for everybody to see”, said Zickay, one of the leaders, as the packets were doused in petrol and set ablaze,” so it sends a signal to the sellers and the suppliers: if they get you, they’ll burn your drugs”.

However, the” sellers and suppliers” at the top of this chain, thousands of miles away in India, were churning out millions more and becoming wealthy on the profits of misery even as the flames burned a few hundred packets of Tafrodol.