When you look at modern China, you are witnessing something stupendous – a great civilization at the peak of its relative power and effectiveness. Along a few dimensions, modern China is the most impressive civilization humanity has ever built. It has the highest total GDP of any country in history, measured at purchasing power parity.

Its manufacturing prowess is unmatched in world history, in relative terms rivaled only by US dominance after World War II. It has a high-speed rail network and an auto industry that put the entire rest of the world in the shade. By some measures, it is now the world’s leading scientific nation. The skylines of its great cities, rearing into the sky and festooned with multicolored lights, eclipse even those of New York and Dubai.

What makes China even more special is that it’s the only major world power experiencing this sort of peak in the early 21st century. The US is divided, chaotic and hobbled by excess cost; Europe, the UK, Japan and Russia are experiencing steep relative decline. The next crop of rising powers, especially India, is still far from its peak. Other than a few smaller countries like South Korea and Singapore, China really stands alone.

And yet, there is something decidedly melancholy about China’s moment in the sun. When I read about the country, or talk to the people who’ve been there recently, I find myself thinking about how much greater of a nation it could be, if its leadership wanted.

Every year, I make sure to read Dan Wang’s letter from China, a blend of fun travel writing, subtle political and social insights, and speculation on technology and business.

Only this year’s letter was not from China; it was from Thailand, where a bunch of young Chinese expats are weathering the storm of their home country’s sluggish economy and political crackdowns. In this expat community, Wang sees a reflection of China’s current situation:

In Chiang Mai, I encountered a great mass of young folks who no longer wish to live in China…Most of the young Chinese I chatted with are in their early 20s…They told me that they’ve felt a quiet shattering of their worldview over the past few years. These are youths who grew up in bigger cities and attended good universities, endowing them with certain expectations: that they could pursue meaningful careers, that society would gain greater political freedoms, and that China would become more integrated with the rest of the world. These hopes have curdled. Their jobs are either too stressful or too menial, political restrictions on free expression have ramped up over the last decade, and China’s popularity has plunged in developed countries.

So they’ve [run]. One trigger for departure were the white-paper protests, the multi-city demonstrations at the end of 2022 in which young people not only demanded an end to zero-Covid, but also political reform. Several of the Chiang Mai residents participated in the protests in Shanghai or Beijing or they have friends who had been arrested. Nearly everyone feels alienated by the pressures of modern China.

A few lost their jobs in Beijing’s crackdown on online tutoring. Several have worked in domestic Chinese media, seriously disgruntled that the censors make it difficult to publish ambitious stories. People complain of being treated like chess pieces by top leader Xi Jinping, who is exhorting the men to work for national greatness and for the women to bear their children.

The existence of this community is not, by itself, proof that China is stumbling. It is not unusual to find a “lost generation” of disaffected young people leaving their home country even at its height of progress and power; the US had its Paris expats in the 1920s and the Beat and Hippie generations in the mid-20th century.

But when you look at the data on the economy that these young expats left behind, the picture gets cloudier. Growth has slowed due to the massive and ongoing real estate bust – official numbers say China grew at 5.2% in 2023, but more sober private estimates put it at somewhere around 1.5% to 3.6%. And even those who take China’s official numbers at face value expect it to slow to only slightly higher than developed-country levels over the next five years.

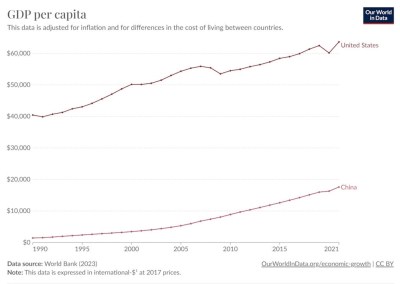

That wouldn’t be a terrible performance for a developed nation like South Korea or France. But for China, that long-term slowdown will come at a much lower level of income. Keep in mind that although China has grown mightily in percentage terms, in absolute terms its gap in living standards relative to the US is actually larger than it was in 1990.

Other countries like Japan slowed down when their living standards were fairly close to those of the richest countries. China is only at 28% of US per capita GDP. When the US, the UK, Japan, and Germany hit their relative peaks, they weren’t just among the largest economies on the planet, but also the richest; China is very large, but it is not rich.

The main reason for this is that China’s productivity growth – the ultimate driver of any nation’s long-run growth after it finishes building out its capital stock – had slowed almost to developed world levels even before the real estate bust:

There are many possible reasons for this premature productivity slowdown. Most of them point to excessive command and control. For decades, China averted recessions by steering massive investment toward less-productive real estate.

Xi is now trying to steer an already manufacturing-heavy economy toward even more manufacturing; in the meantime, service industries like health care, education, internet services and entertainment, which Chinese people probably need a lot more of, have been either neglected or actively cracked down on.

In other words, the Chinese Communist Party, especially under Xi Jinping, has focused China’s economy on creating more of what they want, instead of creating more of what the Chinese people themselves want. This may be one reason that popular confidence in China’s government is beginning to wane.

Technologically and scientifically, China is clearly now among the world’s leading nations; in some respects, it’s ahead of the US. But it’s very hard to think of major new discoveries or inventions that have come out of China in the past quarter century.

The lists of notable items are very short and they’re dominated by the accomplishments of members of the Chinese diaspora who did their groundbreaking work while living in the United States and then moved back to China much later. (This is in contrast to Japan, whose list of modern inventions and discoveries is incredibly long and impressive.)

That doesn’t mean Chinese innovation has failed to transform the world. It has. The quadcopter drone and the lithium-ion battery were invented outside China, but Chinese companies have scaled these industries up to the point of mass usability.

This is similar to how the US scaled up the auto industry in the early 20th century, despite the car having been invented in Germany. Scaling an industry from an expensive, finicky niche product to a reliable, affordable, mass market staple requires a vast accumulation of small feats of innovation and ingenuity.

But in terms of more breakthrough innovations, China continues to lag. This probably isn’t due to the country’s middle-income status – it has plenty of money to throw at R&D but it tends to receive a low return on that investment. Nor is the deficiency due to some sort of deep-seated lack of inventiveness on the part of Chinese people; the Chinese diaspora living in the US is a backbone of its scientific establishment and regularly turns out breakthrough discoveries.

Instead, China’s system simply doesn’t reward invention as much as it should. The country’s intellectual property system is still mostly a sham; as Kai-Fu Lee memorably describes in his book “AI Superpowers”, copying and/or stealing innovations is the norm.

There’s little incentive to invent something really big if it’s just going to get instantaneously and cheaply copied by a dozen other fast followers. This creates a sort of “involution”, where ruthless competition makes individual achievement futile.

(I also suspect — though I can’t yet prove — that Xi and his regime consistently steer research funding toward technologies they think would help China win a hypothetical war against the US and its allies, rather than things that would benefit humankind as a whole. This would be consistent with the government’s emphasis on “national security” in every domain of Chinese life.)

In his book, Lee recognized this weakness in breakthrough innovation. He argued that China will still dominate the AI industry because all the big breakthroughs had already been made, and that the future would see only incremental improvements. The book was published in 2018; just a few years later, generative AI exploded on the scene.

It’s possible that like Lee, China’s government believes that the low-hanging fruit of science and technology has been picked and that scale and incremental innovation are all that’s needed to dominate the industries of the future. But even if that’s correct, note that the goal of dominating an industry is very different from advancing the productivity frontier.

By creating a world where any invention gets immediately stolen and any industry pioneer gets ruthlessly outcompeted by heavily subsidized fast-followers, China’s leaders might further their own relative market share and power at the expense of global technological progress.

If modern China’s scientific accomplishments have been lacking, its artistic and cultural influence is practically nil. Wang sums it up thus in his letter:

Controls on free expression are stronger than they have been in decades. As I’ve written previously, the party’s strangling of free expression has rendered China a pitiful underperformer relative to Japan and South Korea in the creation of cultural products.

What are the great Chinese creations of the last 20 years, aside from a science fiction trilogy published before Xi took office, a short video app that doesn’t display Chinese content overseas, and a video game that looks as if it’s thoroughly Japanese?

In terms of China’s artistic and cultural influence on the rest of the world, Wang is certainly correct. Cixin Liu’s “Three Body” and its sequel novels put Chinese sci-fi on the map. But that was almost two decades ago now and Chinese science fiction output has been woefully thin.

The video game Genshin Impact became a hit with a Japanese-sounding name and imitation of Japanese stylings; other than that, China hasn’t produced many notable games. TikTok is an innovative content platform but the content Americans see on it is mostly produced in America.

I can’t say whether Chinese art and cultural output inside China is good or not. The reason is that I have no idea if it’s good. The fundamental problem, when it comes to Chinese cultural influence, is the Great Firewall; Chinese people can’t easily consume foreign media and the Chinese internet is a walled garden that shuts foreigners out.

As a result, China’s vast population remains mostly invisible on the global internet and there’s little opportunity for Chinese culture to win international mindshare through person-to-person contact. Contrast this with India, which is already transforming global online culture.

On top of all that, of course, China heavily censors its own media output, reducing stories to bland anodyne stuff that has no chance of offending anyone in the government. And the government’s tendency to hand out harsh penalties for any creators who step on its toes undoubtedly produces a chilling effect that goes far beyond explicit censorship.

Whether the domain is the economy, technology or culture, we see the same pattern again and again. China’s government, especially under Xi Jinping, is obsessed with controlling everything the Chinese people do. This limits the greatness of the Chinese nation because any nation’s greatness is ultimately generated by the independent and spontaneous efforts of its people.

It’s not clear what the point of all this social control is. Obviously, one purpose is preparation for a potential war with the US. But even if Xi decides not to start World War III – as I think he very well may not – I can’t see him giving up the idea that the lives of Chinese people need to be micromanaged. At some point, social control becomes its own justification.

This is why I so often feel disappointed when I read about modern China, despite all the bullet trains and batteries. A truly great nation has confidence in its people – not just in their ability to accomplish the tasks they’re assigned but in their ability to assign themselves tasks and to make the world better as they see fit.

China’s leaders seem to lack that confidence. They appear to believe that Chinese people are of some inferior breed, who aren’t capable of using individual autonomy to better the nation and the world, and who must therefore be treated like robots.

In fact, I’ve heard that sentiment expressed explicitly on multiple occasions, from critics of the Hong Kong protests. And Jackie Chan said it back in 2009:

I’m not sure if it’s good to have freedom or not…If you’re too free, you’re like the way Hong Kong is now. It’s very chaotic. Taiwan is also chaotic…I’m gradually beginning to feel that we Chinese need to be controlled. If we’re not being controlled, we’ll just do what we want.

Well yes, people doing what they want is kind of the point of freedom.

All my life, both Chinese people and people of Chinese descent have been a major part of my social circle. My best friend from high school was born in Shanghai and my best friend from grad school was born in Beijing. I can say without reservation that these have all been among the most creative, entrepreneurial and civic-minded people I’ve ever known.

A nation of 1.4 billion such people, if allowed to pursue their own dreams and desires, would be absolutely unstoppable. It would be greater than the US – greater than any country in history, not just in a few respects, but across the board. Instead, China’s leaders are choosing a more cramped and limited path.

This article was first published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion Substack and is republished with kind permission. Read the original and become a Noahopinion subscriber here.