Yuan Yang is what” 1.5 technology immigrant” refers to in terms of movement, meaning she was born in her country of origin and later immigrated to another country as a child.

She belongs, also, to what Chinese people call jiulinhou – the generation of people born in the 1990s. She is interested in the experiences of people like her, who are young people who are determined to make a difference in their life.

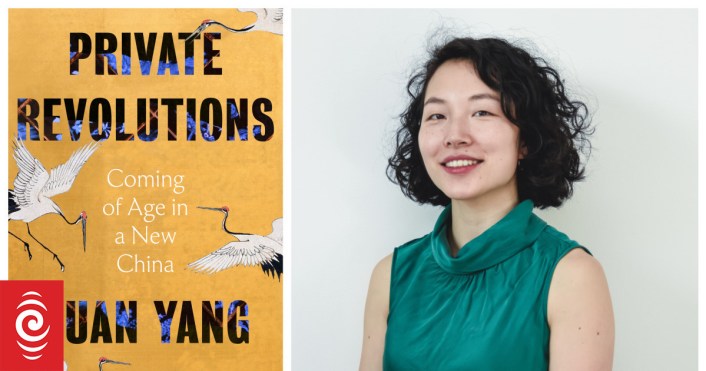

Private Revolutions: Coming of Age in a New China – Yuan Yang ( Bloomsbury )

Yang, a journalist who covered China for the Financial Times, has firsthand experience with the newspaper stumblings of Chinese investigating. In fact, according to a recent study, the majority of articles published in English media between 2020 and 2023 framed China negatively or clearly. For many, difficult reasons, the powerful image of China constructed by foreign correspondents is generally one- dimensional, simplistic, and exceedingly conforms to a Cold War editorial framework.

Significantly, China is portrayed as an economic powerhouse, an autocratic government and a safety hazard. Some international correspondents, after a stay it, feel they know much about China to create books. Some say to have discovered the true meaning of China. In response, Western readers generally perceive the Chinese people as a rock and soulless crowd, divided between those who are victims of a restrictive Chinese regime and brave individuals who dare to challenge the system.

Ordinary Chinese citizens are repeatedly missing from their commonplace, ordinary daily life. Although the media coverage of rural-to-urban migration in China is prevalent, rural migrants ‘ social and personal lives, including their dreams, worries, and frustrations in personal life, especially in close, interpersonal relationships, are largely unfamiliar.

Yuan Yang may not have been able to leave the Financial Times ‘ negative view of China reporting as a blogger trying to follow the editorial mission of her papers. But, her guide does not fall into this trap. For this reason, she might not be able to surpass Jung Chang’s phenomenal fame, the author of Wild Swans, a story about three years of Chinese women, which some claim appealed to Western viewers ‘ pre-existing views. Complexity and complexity are not always valued in publishing.

In the decades that followed the 1980s, when China transitioned from a communist nation to a liberal market economy, Yang’s book Personal Revolutions is set in the years of economic reform. As a result of this transition, state support was gradually withdrawn from initiatives aimed at improving the economy’s health, education, and employment.

Women’s inner selves have unavoidably changed as a result of the gradual outsourcing of responsibility for such services to individual people. This is known as the deregulation of consciousness in some China researchers. The people in Yang’s text are caught up in this cultural change. They respond to, deal with, or even succeed in a spectacular new planet, as they do in their own stories of inward trend.

overcoming the issue of dread

Four people who grew up from the 1990s are the four who are the ones who are portrayed in Yang’s story. Three were born in rural China in very polite conditions. The third was a child of rural migrants and was born and raised in the area. In their settlements, we follow their life from the key to the middle class.

Their lives revolve around leaving the village, getting a job in the city, finding a living companion, and in some cases, raising kids. All of them fight, with varying success, with policy considerations, home anticipation, and the peculiarities of personal situation.

Siyue, whose families left the village to begin a business in Shenzhen, spends her childhood in remote Jiangsu province with her mother before running a private education company in Beijing. She is pregnant after a person abandons her as a single mother and three-year-old girl, Eva. Nevertheless, she prefers to bring up Eva with a” two- person group” ( herself and her mother ) rather than get a partner.

While she’s raising a baby, Siyue’s training company is surviving despite suffering a significant loss during the Covid quarantine. The greatest fear in life is concern itself, Siyue has learned from experience. Talking to kids living with the stress of China’s standard education system, who fear their son’s failure, Siyue usually says,” You have to solve the problem of fear before you resolve anything more..

‘ We’re together are n’t we?’

In the mountainous region of southern China, June was born into a poor family of miners. She works in a garment factory close to Shanghai after losing her mother in a mining accident as a teenager. She diligently pursues her studies to get into a subpar local university before moving to Beijing where she falls in love with a man and begins looking for work while working as a private tutor.

She and her boyfriend find Beijing to be too expensive for them to purchase an apartment, despite her diligent exploration of the opportunities it has to offer.

The population of China is divided between those with residential registration status and those with urban hukou. They are not entitled to the housing, education, and health care benefits offered by nearby urban residents as temporary hukou holders.

It is challenging for them to settle down. Her boyfriend wants to get married, but she does n’t see the point of marriage or having children. Whenever he brings up the topic, she says”, We’re together, are n’t we?”

June is proud to earn enough money to live in Beijing and still send some back home to support her family in the village, even though she is not a woman who “has it all.” To June, success is about” finding meaning in work and feeling a sense of progress and accomplishment.”

Labor activism

Leiya’s parents go to Shenzhen to work, leaving her behind in the village with her grandparents. Like many” left- behind children,” she drops out of high school and goes to Shenzhen to try her luck. After working in different factories, she becomes involved in labor activism. This requires that she find ways to fend off numerous bureaucratic pressures while maintaining a job at the factory and raising her daughter.

Leiya is aware of numerous female migrant workers in their 50s from various Chinese provinces. These women are approaching retirement age. Some people fear being laid off before receiving enough social insurance to retire with a pension, while others do n’t have any social insurance at all.

Leiya wants to assist these women in some way. She establishes a support center to represent migrant women with funding from a charitable foundation and the local government. She constantly advises them against always analyzing their boss ‘ viewpoints in order to empower them. We’re all trained to be good obedient children, but what do you want?”

Leiya and her husband have to work through her daughter’s generational conflict. Her daughter sees Leiya as stingy with money, rude and uncouth. Leiya sees her daughter as tempestuous and disobedient, wasting money on make- up and fashion. She wishes her daughter would instead pursue academic endeavors.

Then there is Sam. She is the only woman who, despite her parents ‘ humble background, manages to live an urban, middle- class life. She was born in Shenzhen, where her parents worked in factories. She met the author as a sociology graduate studying Chinese labor policy at a university in another city.

Sam has developed a strong interest in left- wing politics, especially activism in the labor movement. She has served as both an officer and a volunteer for labor-related organizations. Much of her work involves tactfully mediating between the media, the government and labor organizations.

As activism in politics becomes less popular, Sam chooses to travel abroad to pursue her PhD studies. She is not yet certain what her future will be: studying abroad and returning to China to use her academic abilities for labor activism.

A breath of fresh air

Yang’s book is a breath of fresh air. Readers will come away with the knowledge that Chinese people are just like them. They are pursuing their own goals of upward mobility, despite having to live in a very different political system. They’re trying to get ahead in life, often with stress and frustrations, but also with a sense of achievement.

The microscopically accurate lens through which these people’s stories are told is richly informative and illuminates complex issues, including authoritarian rule, migration, and urbanization.

Yuan Yang is at once a reporter, a consummate storyteller, a self- appointed anthropologist and – most importantly– a friend to the people she writes about.

The University of Technology in Sydney is home to Wanning Sun, a professor of media and cultural studies.

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.