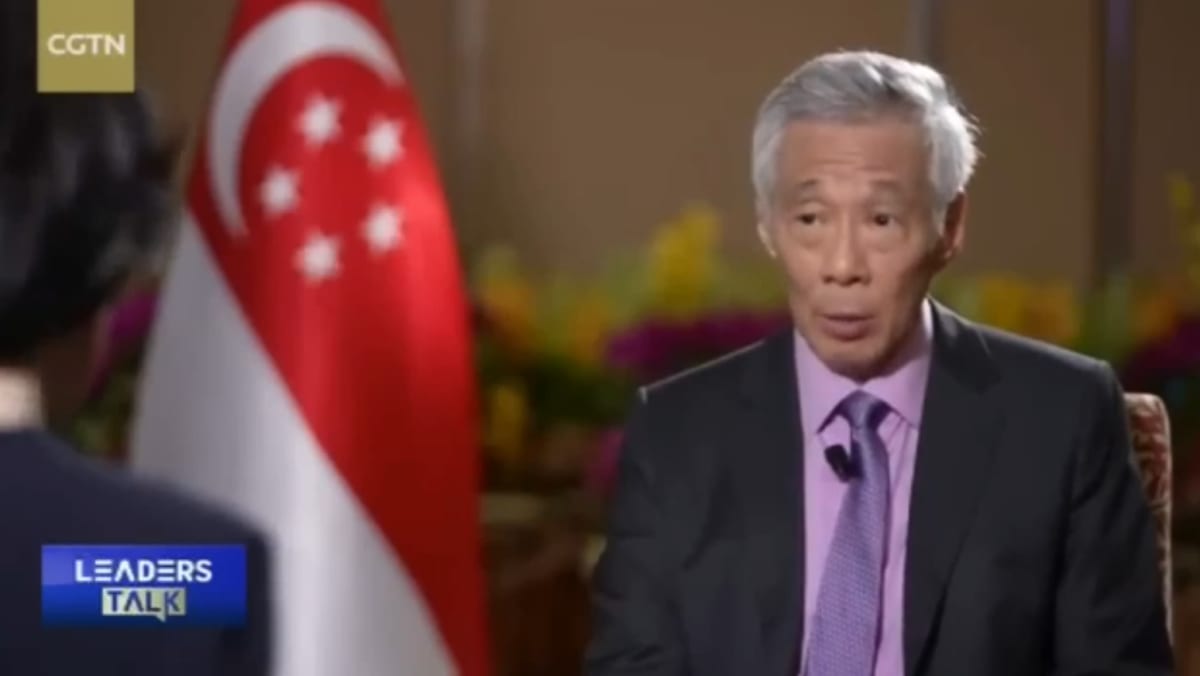

Some deepfakes, like the one of Mr Lee, can be obvious to the more discerning: It’s hard to believe that the Prime Minister would plug dodgy investment opportunities. But the worry is always that such technology would be used for more malicious purposes, such as cybercrime and disinformation.

What happens if, instead of an interview, the manipulated video was of parliament and about issues of import to Singapore?

POLITICIANS, BUSINESSMEN AND JOURNALISTS ARE PRIME TARGETS

As deepfakes are trained on large datasets, public figures such as politicians, businessmen and journalists are prime targets, given the wealth of images and footage available.

Cybercriminals have already adopted deepfakes in their toolbox. Victims of investment scams falling for deepfake videos in Asia have been on the rise while deepfake audio mimicking voices of CEOs have been used to defraud companies. A video of Indian billionaire and businessman Mukesh Ambani was manipulated with a fake voice-over to promote scam investment opportunities.

More worryingly, deepfakes have been used to spread disinformation, to mislead towards malicious ends. In March 2022, in the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a low-quality deepfake video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy urged Ukrainians to surrender.

A deepfake of United States President Joe Biden appearing to announce military conscription in the context of the Israel-Hamas war was widely disseminated in the days after the conflict started. Video footage from a 2021 speech by Mr Biden on insulin prices was adapted and altered with the addition of manipulated audio.