Much like Washington’s stance on Taiwan, China’s position on the invasion of Ukraine has been one of “strategic ambiguity.”

China has consistently emphasized the importance of sovereignty and territorial integrity while failing to condemn the invasion and reassuring Moscow of its “friendship without limits”.

So there has been serious concern in European capitals since Beijing’s ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, suggested that former Soviet Union countries “don’t have actual status in international law because there is no international agreement to materialize their sovereign status.”

Beijing quickly rolled back on this, insisting on Monday (April 24) that “China respects the status of the former Soviet republics as sovereign countries after the Soviet Union’s dissolution.”

Beijing also reiterated its commitment to facilitating a political settlement of the Ukraine crisis. China’s ambassador to the EU, Fu Cong, even used his interview with a Chinese news outlet to claim that his country’s cooperation with Europe was as endless as its ties with Russia were unlimited.

Chinese president, Xi Jinping, reportedly held a “long and meaningful” telephone call with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky – the first time the pair has spoken since Russian invaded more than a year ago.

Chinese state media reported that Xi told Zelensky China would not “add fuel to the fire” of the war but that peace talks were the “only way out” of the conflict, adding: “There is no winner in nuclear wars.”

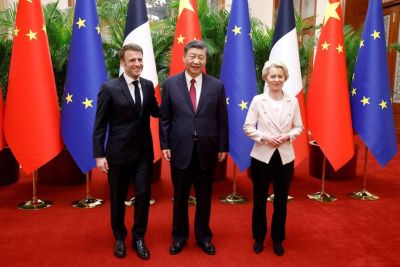

That EU-China relations have been deeply affected by the war is no secret. Recent visits by French President Emmanuel Macron, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock have left no doubt in this regard.

Yet, they also highlighted how diverse European approaches to China are and how they also affect transatlantic relations. While the Western coalition in support of Ukraine has so far held together, it also becomes ever clearer that it has been held together by US leadership economically, politically, and militarily.

This was also evident at the recent EU foreign affairs council meeting in Luxembourg. The bloc’s high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, Josep Borrell, had little new to offer on the EU’s three-track plan to provide Ukraine with one million rounds of artillery ammunition.

Most critically, and most disappointingly for Ukraine, proposals on how to increase European defense production capacity have yet to be finalized.

Similarly, a new EU sanctions package against Russia is unlikely to be concluded until later in May. And the EU and Japan have pushed back against a US plan for the G7 countries to ban all exports to Russia.

All this adds to the question marks already raised about the prospects for a successful Ukrainian counteroffensive in leaked US intelligence assessments.

West divided

It also indicates a continuing and deep uncertainty – and division – in the west over whether, how and what to negotiate with Russia.

On the one hand, there are those who urge the West to double down and dramatically increase its military support for Ukraine. Others advocate for a new strategy that will move the contest from the battlefield to the negotiation table.

Both approaches have their own inner logic. Both want to avoid a prolonged, damaging stalemate on the battlefield.

Such a stalemate would not just impose further costs on Moscow and Kiev but also have repercussions far beyond the frontlines in Ukraine. Former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev has already threatened to end the current deal that enables Ukrainian grain exports via the Black Sea.

This constitutes a vital food supply line for many developing countries. If Russia were to pull the plug on the deal, this would also further increase tensions within the EU over transit (and market access) for Ukrainian grain.

Little wonder then that countries like Brazil are keen to see China try its hand at mediating between Russia and Ukraine.

French fears

For the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, clearly more important than Brazil’s support is that of his French counterpart. Macron is allegedly working with China on creating a framework for Russian-Ukrainian negotiations.

However, he has been widely condemned for doing so. Only the Italian defense minister, Guido Croscetto, has seconded the idea that China should be mediating peace talks.

Macron has a track record of, if not openly pushing for negotiations, at least considering ways of establishing credible pathways that can get them started.

In June last year, he was widely criticized for suggesting that Russia should not be humiliated. In December last year, he proposed security guarantees for Moscow, an idea that was similarly ridiculed by Ukraine and other Western allies.

The fact that France remains committed to the need for negotiations, and outspokenly so, however, should not simplistically be seen as a rush to concessions towards Moscow.

It is, in part at least, also a reflection of the very real difficulties that lie ahead on a potential path to a military victory in Ukraine. These difficulties are to some extent of the West’s own making, especially the EU’s own woeful lack of defense capabilities.

But the French position also reflects a fear of further escalation of the war with Russia, as foreshadowed in Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov’s recent speech at the UN Security Council and of an irreversible deterioration of relations with China.

The flurry of European visits to China over the past six months, beginning with German chancellor Olaf Scholz last November, is an indication of how important that relationship is for the EU and its key member states. And that France is not alone in seeking an end to the war in Ukraine sooner at the negotiation table rather than later on the battlefield.

The EU’s inability to make decisive commitments to bolstering Ukraine’s capabilities to win – and curbing Russia’s – is a symptom of a wider contest over what Europe’s vision of the future of international order is and what role it wants to play in it.

By default or design, the outcome of this contest will also decide the fate of Ukraine.

Stefan Wolff is Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.