Huanchun Cao, a 72-year-old producer, responds with a raspy sigh when Huanchun Cao inquires about his pension.

He sucks on his house- rolled smoke, narrows his face and tilts his head- as if the pretty question is immoral. ” No, no, we do n’t have a pension”, he says looking at his wife of more than 45 years.

Mr. Cao belongs to a technology that witnessed the emergence of Communist China. Like his country, he has become outdated before he has become wealthy. He has no choice but to work and keep earning because he has been hampered by a poor social safety net, like some rural and immigrant workers.

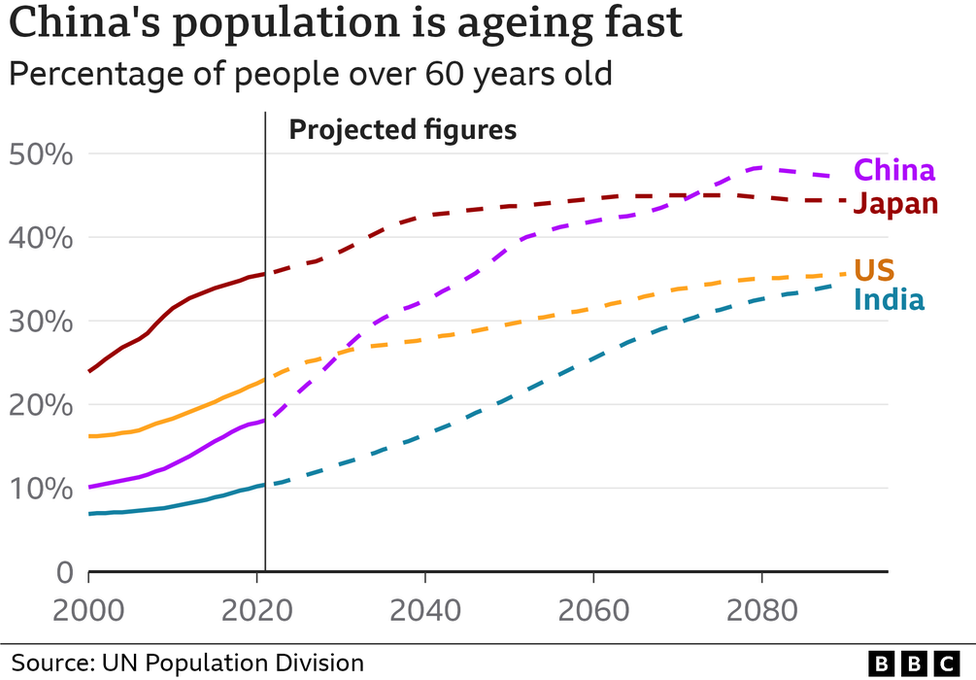

A sluggish economy, shrinking government benefits, and decades-long one-child plan have all contributed to Xi Jinping’s China’s creeping statistical crisis.

The state is running out of time to create much of a bank to provide for the growing number of elderly, and the pension pot is running away.

Over the next generation, about 300 million people, who are now aged 50 to 60, are set to leave the Chinese labor. This is the region’s largest age group, roughly equal to the size of the US population.

Who does look after them? The response varies depending on where you go and who you ask.

Mr Cao and his family live in the north- northeast province of Liaoning, China’s former professional homeland.

The major city of Shenyang is surrounded by vast stretches of land and mined hills. The sky is engulfed by fumes from smelting companies, along with some of China’s best-preserved world heritage sites from the Qing kingdom.

Almost a quarter of the population in this place is 65 or older. An increasing number of people in their working years are leaving the center of large industries in search of better employment in bigger cities.

Although Mr. Cao’s children have also moved away, they are also close enough to visit frequently.

When Mr. Cao and his wife returning from wood-collecting, he says,” I think I may just continue doing this for another four or five years.” Inside their house, flames crackle beneath a cooked system- called a “kang”- which is their primary source of warmth.

The couple make around 20, 000 yuan ( £2, 200,$ 2, 700 ) a year. However, the cost of the corn they grow is declining, and they are unable to manage to become ill.

” In five years, if I’m still physically powerful, even I can walk by myself. However, I may be confined to bed if I’m weak and feeble. That’s it. Over. I’m going to have to bear with my kids, I suppose. They will have to look after me.

That is not the potential 55- season- old Guohui Tang wants. Her sister’s university education was ruined by her husband’s incident at a construction site, and her daughter’s savings were wiped out by their daughter’s success.

The original digging operator saw a need to help pay for her own senior treatment. About an hour from Shenyang, she opened a little care facility.

At the back of the single-story home, which is surrounded by land, the pigs and birds both greet visitors. Mr Tang grows crops to supply her six people. They are also used as supper, no as animals.

As the moon passes through the little pavilion, Ms. Tang points to a group of four playing cards.

” See that 85- season- old man- he does n’t had a pension, he’s relying wholly on his son and daughter. His boy pays one fortnight, his daughter pays the second month, but they need to live to”.

She worries that she will have to rely on her only daughter, saying,” I will now pay my pension every month, even if that means I ca n’t afford to eat or drink.”

For decades, China has relied on filial devotion to fill the gaps in old treatment. It was a son or daughter’s duty to look after ageing kids.

However, there are fewer sons and daughters available for older relatives to depend on. One reason for this is the “one-child” diktat, which forbids couples from having two or more children between 1980 and 2015, which was in place.

Younger people have also abandoned their families, leaving a growing number of seniors to take care of themselves or rely on state aid as the economy has grown faster.

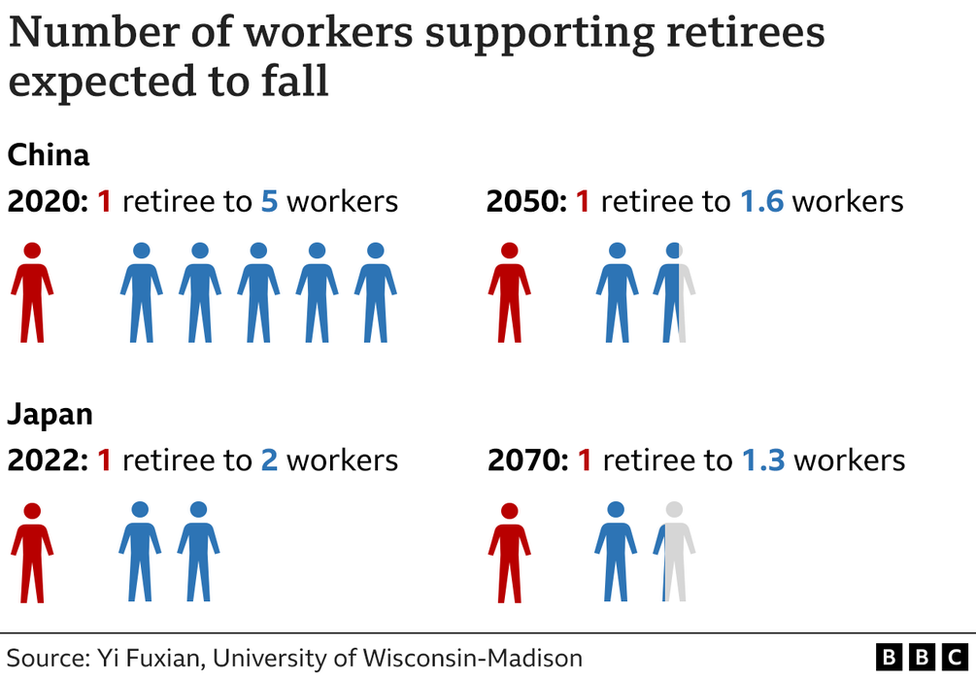

However, the state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences predicts that the income fund will run out of money by 2035. That was a 2019 estimation, before the pandemic shutdowns, which hit China’s market hard.

China may also be forced to raise the anticipated pension years, which has been in place for decades. It has one of the lowest pension age in the world- 60 for males, 55 for whitened- neck women and 50 for working- group women.

However, according to economists, this is just tinkering around the edges if China wants to avoid what some people fear may turn into a humanitarian crises in 25 years.

However, more and more old have been dipping into their incomes.

” Welcome to my home”, beckons 78- yr- old Grandma Feng, who just wanted to employ her next name.

As she frantically races down the corridor to inform her father that visitors are arriving to their place at the Sunshine Care Home, it’s difficult to keep up with her. She had just finished her dawn workout class, where she had been giggling and talking to her friends again in secret.

The home was built to building more than 1, 300 people. In exchange for assisting some of the old, around 20 young people volunteer to sit here for free. Private companies pay a portion of the cost of the home, removing the stress from the neighborhood state.

Officials are looking for solutions to an aged China through this test. These in Hangzhou, in southern China, they can obtain for research.

This is a completely different world from Liaoning, where gleaming new buildings like those found in Silicon Valley house tech firms like Alibaba and Ant, a magnetism for ambitious, younger companies.

The Fengs have resided here for eight times. The nursing home appears welcoming and there is plenty to do, from the treadmill and table tennis to chanting and play.

According to Grandma Feng,” It is very important to be able to accomplish the next phase of life in a good place.” She and her partner have been together for more than 50 years. It was love at first sight, they say.

When their nephew left junior high school, they decided their work was over.

There are” no people of the same age who think like us,” according to Grandma Feng. We appear to care more about having fun with existence. Those who disagree disagree that having a home on their own makes it superfluous to spend a lot of money.

But she says she is more “open- thinking”:” I thought it through. I recently sold my home to my brother. Our income accounts are all we need right now.

The child’s room at the treatment home costs around 2, 000 renminbi a month. Both former state-owned workers have much income to cover the cost.

Their income is much higher than the average in China, around 170 yuan a quarter in 2020, according to the UN’s International Labour Organization.

The Sunshine Care Home is operating at a loss despite having customers who are financially stable. Care properties are expensive to start up, according to the chairman, and take time to succeed.

Beijing has been urging private companies to establish daycare facilities, wards, and another age-related equipment to fill the void left by overburdened local governments. But if the future holds out, did they continue to invest?

Another East Asian nations, like Japan, are even looking for funding to care for a large number of seniors. However, Japan had one of the largest age groups in the world by the time it was already rich.

China, however, is ageing quickly without that seat. Some older people are now forced to make their own decisions at a time when they ought to been planning their retirement.

In an effort to harness the purchasing power of middle-class seniors, fifty-five-year-old Shuishui found a new career in what is being called” the silver-haired economy” ( the” silver-haired economy ).

” I believe what we can do is try to make people around us feel more optimistic and to maintain learning,” she said. Everyone may have varying degrees of household income, but whatever situation you’re in, it’s best to remain optimistic.

Shuishui is aware that she belongs to a wealthy family in China. But she is determined to wait and see what comes. The original woman has received design training.

On the beautiful institutions of the Grand Canal in Hangzhou, she and three other ladies, all over 55, are touching up their make- away and scalp.

Each has chosen their own traditional Chinese outfit in red or gold, wearing floor-length silk pattern skirts and fur-lined short jackets to thwart the spring chill. These opulent grandmothers are using social media for modeling.

As a team of social media experts yell instructions, they teeter dangerously in high heels over the cobbled historic Gongchen bridge while trying to laugh and smile for the camera.

Shuishui is eager for the world to see this graceful image of greying, and she feels like she is doing everything she can to help an ailing economy.

However, this picture defies the reality for the many elderly people in China.

Back in Liaoning, the wood smoke rises from chimneys, signalling lunchtime. Mr. Cao is using the fire in his kitchen to heat the water to cook the rice.

As he searches for a saucepan, he says,” When I reach 80, I hope my children will come back to live with me.”

” I’m not joining them in the cities. You have to climb five floors to reach their place because it has no elevator. That’s harder than climbing a hill”.

This is simply the way things are, according to Mr. Cao. He must continue to work until he is no longer.

Ordinary people like us live like this, he says, pointing to the still-frozen fields outside. The planting season will return this spring, and he and his wife will have more work to do.

” If you compare it with life in the city, of course, farmers have a tougher life. How can you make a living if you ca n’t bear the toughness”?