Days and nights in Kyoto

Days and nights

Night and days

In Kyoto

Welcome to information retrieval

– Michael Kamen, Brazil

As the threat of deflation stalks China’s economy, the China-watching herd has resurfaced an old question from the rotation: Is China turning Japanese? The well-known script, in the words of a media-anointed analyst:

China’s economic growth has followed what’s sometimes called “the Japanese model.” In Japan and other Asian countries, this model has proved extraordinarily successful in the short term in generating eye-popping rates of growth – but it always eventually runs into the same fatal constraints: massive overinvestment and misallocated capital. And then a period of painful economic adjustment. In short: Beijing, beware.

According to the narrative, China is now facing a Japan-style reckoning with its property sector stuck in the doldrums for over three years. Of course, the above quote was written in 2010 when China’s economy was less than half its current size and annual investment in residential property would still triple. Some people just like to be early.

Japan is sui generis. No nation’s economy has underperformed so lamentably for so long after outperforming so spectacularly for even longer. It’s just not true that every country that has followed “the Japanese model” has had to suffer long periods of painful economic adjustment – at least nothing approaching Japan’s malaise.

None of the four Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore) have experienced multiple decades of stagnation. And all of their per capita GDPs, coming from far behind, now exceed Japan’s on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis.

South Korea shook off the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, reformed its chaebols and moved up the value ladder. Taiwan integrated its economy with the mainland and became the world’s leading producer of semiconductors.

While Hong Kong’s recent decade has been lousy, it was the result of underinvestment in housing and, at the end of the day, the trade and financial hub still outperformed Japan. And Singapore is just a rocket ship with a per capita purchasing power parity GDP now 2.6 times that of Japan’s.

While the Asian Tigers’ birthrates started declining about ten years after Japan, they fell more precipitously and at lower per capita GDP levels. Taiwan’s birthrate has just about fallen to Japan’s level while South Korea’s has sunk far below. Singapore and Hong Kong population charts look no better despite immigration being a viable option.

What did not happen in any of the Asian Tigers is the hoary “getting old before getting rich” canard. Collapsing birthrates did not, in fact, prevent any of the Asian Tigers from catching up to and exceeding Japan’s per capita GDP.

While the night is still young and the consequences of disastrous-looking population charts may still catch up with the Asian Tigers, falling birthrates since the 1980s may have perversely allowed two generations of Asians to devote themselves to career and commerce, fueling decades of growth.

China’s birthrate had been comfortably higher than those of Japan and the Asian Tigers until surging university enrollment and Covid lockdowns (see here) caused a nosedive in recent years.

Still, China’s population under 20, at 23.3%, is considerably higher than its Asian counterparts (16-18%) and in line with the US (25.3%) and Europe (21.9%). The country’s 65 and older population, at 14.6%, is also lower than that of the developed world (20.5%).

While China will not lack young workers for another two decades, it remains to be seen whether births bounce post-Covid and as university enrollment plateaus.

Compared to the Asian Tigers, China is the least likely to suffer Japan-style economic stagnation as a result of demographics, which, in any case, none of them has (yet).

The underappreciated cause of Japan’s lost decades is the degradation of its human capital. In 2022, Japanese universities produced as many science and engineering grads as they did in 1990, despite a doubling of enrollment rates at four-year universities.

Starting in the mid-90s, as the youth population dwindled, four-year universities in Japan started to dip into the junior college bench, which enrolled 14% of Japanese post-secondary students in 1995.

By 2013, junior college enrollment fell to 5% while four-year college enrollment increased from 31% to 55% in the same period.

At the same time, those choosing to study science and engineering fell from 24.5% in 1971 to 18.1% in 2016 as Japanese STEM students gravitated towards medicine, in which enrollment saw a threefold increase in percentage terms.

The combined effect of dipping deep into the bench and losing STEM students to fields like medicine can only have lowered the quality of scientists and engineers that Japan did manage to produce.

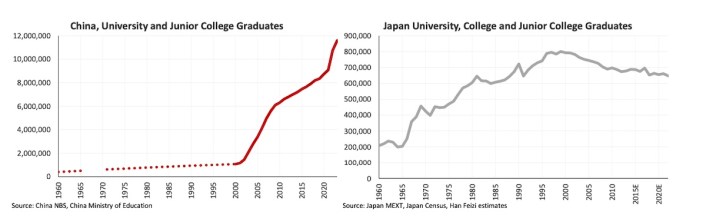

With college graduates having plateaued in the 1970s, Japan is long past the era where its universities are adding educated employees to the workforce.

Japan, like the rest of the developed world, is now in replacement mode and, given the dwindling youth population, is forced to graduate students of ever-decreasing ability.

China, in contrast, has not yet plateaued in enrolling students in higher education. From single-digit university enrollment rates at the turn of the century, in 2022 China enrolled 34% of its 18-year-old age cohort into four-year degree programs and 29% into junior colleges.

If college enrollment plateaued today, China’s college-educated workforce will increase fourfold over the next 30 years.

The proportion of Chinese students majoring in science and engineering at four-year universities was 41% in 2015 (the last year of reported data), more than twice Japan’s level. At the junior college tier, 43% of students were studying technical fields (and 13% in healthcare.)

While China’s surge in higher education over the past two decades drove its industrial and technological growth, Japan has been retrenching along with its human capital.

With births declining for decades and college enrollment long plateaued, Japan’s educated workforce peaked in the late 1990s. We are now witnessing a long sunset.

Japanese patent applications have fallen 44% from their 2000 peak. Its annual domestic patents filed fell from over 25% of the world’s total to 3% in 2022. Japan published over 9% of the world’s scientific papers in the late 1990’s and only 3.4% in 2020.

From second to the US, Japan’s scientists have fallen to 10th place in the publication of the top 1% of papers by citation. Similarly, Japan’s share of global manufacturing output has fallen from over 20% in 1995 to 6% in 2021.

China’s surge during Japan’s decades of slow decline is well known. All China charts for the past four decades look the same – upwards and to the right at a 45-degree angle.

What is more intriguing is South Korea’s charts. Even as birthrates plummeted, South Korea was able to increase patents filed as well as scientific papers published, more or less matching Japan with less than half the population.

Similarly, South Korea has maintained its percentage of manufacturing value-added even as the China juggernaut swallowed up market share from everyone else.

The terrifying secret behind South Korea’s success is the nation’s savage dedication to education. For the past two decades, South Korea’s gross enrollment of its 18-year-old age cohort in higher education has been around 100% with some years exceeding 100%.

What this means is that South Korea has run out of 18-year-olds and is enrolling older students in universities to produce the workers it needs.

Analysts tend to attribute Japan’s economic malaise to financial mismanagement with demographics looming in the background like a chronic disease. It’s more complicated than that.

Japan never recovered financially, economically or socially after the US kicked its legs out from under it in the 1980s and 90s with the Plaza Accord, the evisceration of Toshiba and humiliating “voluntary” export quotas on cars.

Mismanaging an asset bubble, shielding the service industry from competition and keeping zombie companies on life support certainly didn’t help. But given the Plaza Accord’s constraints on the yen and the neutering of leading industrial giants, it’s not surprising that Japan retreated into a pot much smaller than the one it had occupied and once imagined for itself.

Japan suffered from nothing less than a loss of vitality as a bonsai’ed people dealt with lowered ambition by withdrawing from society (hikikomori), becoming “herbivores” (celibate) and marrying their kawaii anime pillowcases.

Despite dipping into the junior college bench and educating a larger proportion of the population, Japan just could not offset its declining and demoralized youth by making them higher-quality workers. And as such, the country fell precipitously down the science, technology and industrial league tables.

South Korea, on the other hand, with a smaller population and similar demographic profile, has heroically outcompeted Japan in semiconductors, consumer electronics, chemicals and shipbuilding. The country’s contribution to global scientific papers and patents has continued to increase and its per capita GDP surpassed that of Japan in 2018.

In the past two decades, South Korean youths have become the world’s most educated with over 70% of the population between 25 and 34 having completed tertiary education (versus 50-60% in other highly educated OECD countries).

While seemingly succeeding, the cure may be exacerbating the disease. Korean youth have an educational experience that reformers liken to child abuse.

Koreans appear to have taken education to whole new levels of Asian madness. For-profit cram schools (hagwons) were established decades ago for remedial test preparation. Today, they have taken over the education system, enrolling the majority of Korea’s five-year-olds.

The upshot of outrunning demographic decline through intense education, which South Korea has apparently succeeded in doing, is that an overworked and educationally ground-down population are now having even fewer children.

South Korea’s 2023 fertility rate per woman was a catastrophic 0.72 (with 2.1 necessary to maintain current levels of population). What this all means is that while South Korea has outrun “Japanification” for the time being, the eventual reckoning threatens to be catastrophic.

Today, like in 2010, commentary on China’s Japanification is far off the mark. China bears only superficial similarities with Japan, namely a property bubble, which in China’s case is so far a controlled demolition rather than chaotic collapse.

China’s human capital upgrade is just beginning to hit its stride while, in the 1990s, Japan’s was peaking. China’s college-educated workforce will not peak for another 30 years. To prevent education from eating its young, China recently outlawed the entire for-profit tutoring industry.

In the next two to three decades, China will be flooding its workforce with newly minted scientists and engineers to staff companies you never heard of just a short while ago – CATL, BYD, DJI, miHoYo, BOE.

There will surely be more. Attributing Japan’s lost decades to financial mismanagement is to mistake the symptom for the disease. Japan failed to upgrade the quality of its workforce after the Plaza Accord; it was simply outcompeted by China and South Korea, both of which did.

Analysts who obsess over Chinese property developers’ balance sheets, investment/consumption balances and local government debt are missing the forest from the trees.

How it’s all financed is of tertiary importance. China, like Japan, South Korea or any other economy, has always been a human capital story. It’s people all the way down.