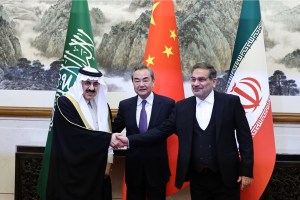

In diplomatic terms, the optics were shocking. Here were representatives from Saudi Arabia and Iran smiling and holding hands in a foreign capital as they announced the restoration of diplomatic relations after a seven-year break.

But the foreign minister in the middle, proudly bringing them together, was not a European or American politician, but China’s Wang Yi.

No words were needed. The message was heard from Washington to Brussels: China’s diplomacy had arrived in the Middle East.

This was the second time in as many weeks that China had played the role of mediator, shortly after proposing a peace plan for Ukraine. Yet it was far more consequential. This demonstration of Middle East diplomacy with Chinese characteristics was not only about bringing together Saudi Arabia and Iran – it was about keeping America out.

It is still too early to see the consequences of the deal, but it has the potential to reshape some of the most serious conflicts in the region, from Yemen to Syria to Lebanon. For now, as the details of the detente are still being worked out, the Iran-Saudi deal is far more relevant for who did the diplomacy than the diplomacy itself.

It is certainly a deal from which everyone wins. Iran looks far less isolated than it did even a year ago.

The war in Ukraine has brought about such a close relationship with Russia that Iranian drones are now being battle tested in that war; there are reports that Russia is handing over to Iran US weapons captured from Ukrainian soldiers (so that Tehran can reverse-engineer them); and, most important, Russia will supply advanced Sukhoi fighter jets to Iran. And now Tehran has resumed relations with its regional rival.

For Saudi Arabia, the optics are almost as important as they are for China. The kingdom’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has made it a hallmark of recent months to put clear blue water between the United States and his country.

President Joe Biden’s visit to Jeddah in the summer of last year was meant to reset ties – but it rapidly fell apart within months as Saudi Arabia and Russia led OPEC+ to a production cut. Washington was furious and Biden issued a rare public threat, vowing “consequences” for Riyadh. Those consequences, so far, have either not happened or not been made public.

This deal, therefore, will be watched closely in Washington, which will realize it is a message that Saudi Arabia is willing to move beyond America’s orbit.

It is surely no coincidence that mere hours before the China agreement was announced, a story “leaked” that named Riyadh’s price for normalizing with Israel. That price – a civilian nuclear program for the kingdom and security guarantees from the US – is steep, and Riyadh’s message is clear: We have other friends waiting.

But the audience for China is far larger than one country. The whole of the Global South will take note of the message Beijing is telegraphing, of a country that can get things done, even in a region where the US considers itself the pre-eminent foreign power.

How far they will believe that message will vary, but it comes soon after Beijing sought to play the “responsible” peacemaker in a war that has become a proxy battle between the West and Russia. Expect to see Chinese diplomacy showcased in unforeseen quarters this year, perhaps in an African conflict.

For now, though, it’s unclear what this new global diplomacy with Chinese characteristics will look like. The Ukraine peace proposal, just like the Iran-Saudi deal, is more notable for the diplomat than the diplomacy. Make no mistake, it is absolutely shocking to see China mediate a landmark Middle Eastern peace deal. But whether that deal will upend the way politics has been conducted in the region is still unclear.

Much more likely is that it will open the door for further outside involvement in the region, rather than lead to a wholesale replacement of the US by China – something most Middle Eastern states probably don’t want, and almost certainly Beijing does not want.

But what it does highlight is a much more gradual shift in the region’s politics, one that the US sometimes seems powerless to resist.

A better metaphor for the changing Middle East is the South China Sea, where, for all Washington’s bluster over freedom of navigation – and even major political changes like the nuclear-submarine deal with Australia announced this week – it does feel as if the US simply lacks the will, rather than the ability, actually to stop Chinese expansion and encroachment.

There may be a series of military drills with Asian countries here, a visit to Taiwan by a US politician there, but overall, the trajectory is in China’s favor.

The same is true for America’s role in the Middle East. The broad trajectory of the superpower’s departure hasn’t really changed. The Syrian Civil War offered Russia the chance to return as a military power, and the Iran-Saudi conflict offered China a way in as a diplomatic mediator, but the direction of travel is clear – not toward China, but away from America.

The Middle East will have to get used to a multipolar region; that reality is already knocking at the door. One day soon, the world may have to get used to it as well.

This article was provided by Syndication Bureau, which holds copyright.

Faisal Al Yafai is currently writing a book on the Middle East and is a frequent commentator on international TV news networks. He has worked for news outlets such as The Guardian and the BBC, and reported on the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. Follow him on Twitter @FaisalAlYafai.