Reuters

ReutersPulling energy. That is what China also has in Africa.

China has forged a thick ground while the control of other countries on the continent is questioned- for example, France and the rest of the EU are being deposed by the Northeastern military juntas and pro-Western African governments regard Russia’s “offer” for mercenary-security with deep suspicion.

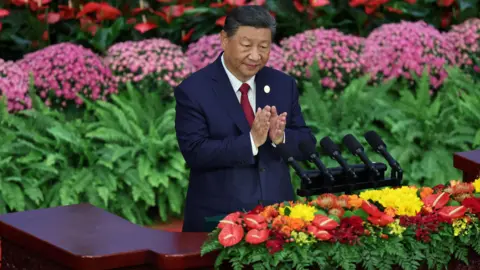

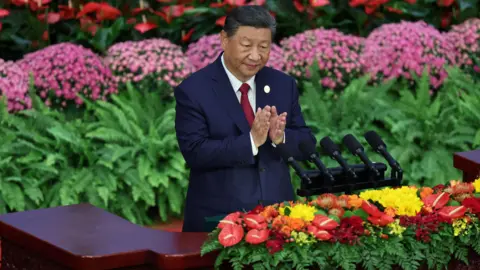

For the most recent China-Africa summit, known as the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation ( Focac ), delegations from more than 50 states from across the continent decided it was worthwhile to travel to Beijing this week.

Lots of officials turned up- as well as UN key António Guterres.

This was Bassirou Diomaye Faye’s first official meeting for the new Senegalese leader of state, who was pictured alongside Congo-Brazzaville strongman Denis Sassou-Nguesso in a family picture of rulers and their spouses.

China now appears to be a wonderfully trustworthy partner, ready to work without prejudice with both the supporters of Moscow and the civilian-ruled states that are closer to Europe and the US, for American governments that are resentful of the stress to take sides in global disputes.

Beijing truly bargains a lot in exchange for development assistance, particularly the development of large system, in order to fulfill its financial self-interest and need for natural raw materials.

AFP

AFPIt is frequently accused of making American nations accumulate too much debt, and it was initially slow to meet the global effort to ease some nations ‘ crippling debtors.

Even then, it refuses to give openly debt cancellations.

Problems that China resources too many skilled structure roles for its own employees, at the cost of training Africans, are widespread. The rising number of Chinese investors has sparked resentments among some of the country’s historically predominate industrial areas.

These are, however, problems for some American governments.

In a world where politics are extremely divided, they find Beijing’s non-partisan willingness to stay firmly engaged almost anywhere, without political restraints.

Of course, it is China’s construction of big-ticket transportation projects that attracts the most interest, which are often handled with caution by Western commercial investors and foreign development institutions.

The July 2023 coup in Niger has not dissuaded the Chinese from completing a 2, 000km ( 1, 200-mile ) pipeline to deliver the country’s growing oil output to an export terminal in Benin.

In Guinea, even under military rule, the China-based Winning Consortium is also advanced in the development of a 600km rail to the beach. This will be funded by Simandou’s largest iron ore deposit, which has been a source of contention for subsequent Guinean institutions.

And this week’s Focac summit brought a continuation of this strategy, with the announcement of a further 360bn yuan ($ 50.7bn, £36.6bn ) in funding, for the next three years.

But this time there is a difference, with a large conference focus on the natural energy transition, including funding in manufacturing in Africa, specifically electric cars.

For a continent that has infamously lagged far behind Asia in developing sophisticated industries, that is significant both in terms of practical and symbolic terms.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, the summit also provided assurances of support for other types of green projects, with Mr. Xi stating that he was prepared to launch 30 clean energy projects and to work with others in the nuclear sector.

That last tidbit touches on a sore point for African commentators who are upset that France has for years mined uranium to supply its own nuclear power sector without making any recommendations for West Africa’s generation projects.

China is also active in the industry that mines uranium in Nigerien.

However, it remains to be seen whether the Chinese president’s promise will actually be more than warm words in the face of the enormously complex technical and security challenges facing the nuclear industry.

Additionally, the Focac summit swayed around some of the more contentious and contentious environmental issues, such as the frequently-cited claims that large Chinese vessels overfish and leave little to catch local artisanal boats.

Princess Dugba, Sierra Leone’s Fisheries Minister, chose to concentrate on praising the country’s government for the construction of a new fishing port.

Mr. Xi, in contrast, argued that his country and Africa together account for a third of the world’s population, perpetuating China’s self-presentation as a fellow member of the “global south.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe summit also approved the Beijing Action Plan for 2025-2027 and the Beijing Declaration on” building a shared future in the new era.”

Mr. Xi called on Chinese contractors to go back to Africa now that the disruptive Covid-era restrictions have been removed, and he mentioned a tripling of infrastructure projects, the creation of one million jobs, and cooperation across a range of sectors.

However, it is not entirely clear what the promised 360 billion yuan in financing will actually amount to in terms of terms that are specific. It appears to be a bid to advance the Chinese currency’s international reputation.

The president said that 210bn yuan ($ 29.6bn ) would be provided through credit lines, while there would be 70bn yuan ($ 9.9bn ) in business investments.

He also made an announcement about$ 280 million in military and food aid, but this is a small sum for an entire continent, in contrast to the big-budget economic funding.

How the new funding is distributed is still to be seen, and whether it is managed in a way that does n’t lead to the return of some nations to unsustainable debt.

China’s efforts to advance the construction of infrastructure over the past 10-15 years were widely attributed for causing them to fall into debt, just two decades after they benefited from international debt-forgiveness schemes.

In 2016, the peak year,$ 30bn in Chinese lending to Africa was announced.

Projects were frequently funded by China Eximbank on terms that were typically kept secret, but they were almost certainly much more expensive than funding from institutions like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the African Development Bank, or the grant assistance provided by numerous Western government donors.

However, it is reasonable to assume that China’s approach was frequently willing to finance and build projects and accept levels of risk in circumstances where other partners were hesitant to invest or commit resources on the necessary scale.

And to some extent, a natural division of labour evolved, where China funded and built heavy infrastructure, while Western donors and the big development institutions financed the equally essential” soft” investments- in health and education, skills training, government systems, food security, rural resilience and so on.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe G20 countries established the Common Framework to restore indebted countries to a sustainable path as the magnitude of the new financial pressures weighing on many nations became clear, especially in light of the pandemic-caused global economic slowdown.

China did participate in efforts to reduce the burdens of developing nations ‘ debt repayments. However, it was accused of not doing enough.

Now, several years on, this week’s Focac summit suggests the picture may be poised for a further evolution.

Beijing now wants to become a key partner for the continent in new hi-tech industry and green technology on a scale that many European and North American companies are unwilling or unable to consider. Two decades ago, China began to play a role in developing infrastructure that Africa’s traditional donors were unable to adequately fill.

While Western investment in Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan countries, continues to be dominated largely by mining, oil, gas and agriculture, and Russia focuses on security services for favoured regimes, Beijing talks of a broader economic vision.

However, the question is whether, beyond Mr Xi’s rhetoric, this will amount to a real diversification into new sectors such as green industry.

Will the conventional emphasis on big infrastructure continue to predominate despite a few niche, high-profile projects?

If the China-Africa relationship is about to undergo a significant change, it is not yet known.

Paul Melly works for Chatham House in London as a consultant for the Africa Programme.

You might also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC