G7 financial markets avoided a threatened crisis September 28 when the Bank of England announced £45 billion of emergency government bond purchases. That amounts to an emergency easing of monetary policy after months of coordinated rate hikes by most of the world’s central banks.

The British central bank, the world’s second oldest, had no choice: Plummeting bond prices threatened the forced liquidation of British government bonds bought with borrowed money by financial institutions.

A margin call in the market for UK government bonds, or gilts, would have disrupted the orderly financing of supposedly safe assets and triggered a forced liquidation of positions across markets, similar to – if not on the scale of – the 2008 world financial crisis.

The Bank of England’s retreat stopped the disintegration of the UK bond market – at least temporarily. US bond markets also rallied, apparently because investors considered the possibility that the Federal Reserve would have to back off from tightening at some point to avoid damage to US financial markets.

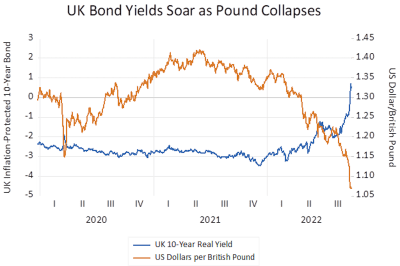

Britain’s two-step around the brink began earlier this week when the newly-formed government of Prime Minister Liz Truss announced massive tax cuts for UK corporations and high earners. This attempt to revive economic growth at the expense of more government debt sent the pound sterling into a free fall that brought it to its all-time lowest exchange rate against the US dollar.

The British government’s cost of borrowing as measured by the yield on inflation-protected UK government bonds jumped as the pound collapsed, threatening the forced liquidation of government bond positions.

Markets have buckled in the face of central banks’ efforts to control inflation, and the market’s standard risk gauge has jumped back to the crisis levels of March 2020, when the first Covid wave hit Western economies.

The cost of hedging US, German, and British government bonds, as well as currency positions in euro or Japanese yen, is measured by the so-called implied volatility of options on those instruments. By this gauge, the riskiness of major markets is back up to March 2020 levels.

In fact, the riskiness of government bond markets is now higher than during the 2008 financial crisis. That’s because government bond targets take the brunt of the impact of central bank tightening and reflect all the uncertainty associated with monetary policy.

Risk in other markets, to be sure, remains muted compared with real crisis conditions. The stock market’s measure of implied volatility, the VIX Index, is elevated, but still below the extreme levels of 2008 or March 2020.

The one monetary asset that does not show elevated risk is gold. As shown in the chart below, the implied volatility of gold options has tracked the volatility of Treasury inflation-protected securities. Under normal conditions, TIPS and gold both offer the same sort of hedge against extreme moves in the inflation rate. In 2008, for example, gold volatility and TIPS volatility spiked together, and the two risk measures have tracked each other closely since then – until 2022, that is.

This time, gold volatility is much lower than – in fact, about half as low as – the corresponding level of TIPS volatility would indicate.

The explanation for this discrepancy probably lies in market skepticism about central banks’ efforts to fight inflation by tightening credit conditions. This inflation didn’t start with a credit bubble, unlike the last big round of inflation during the 1970s. Instead, it began with the central banks’ response to the Covid-19 pandemic and the massive subsidies that governments offered to consumers. The Biden Administration continues to throw money at consumers, for example in the form of a student loan forgiveness program that will cost the Treasury more than $400 billion.

The Federal Reserve squeezed credit, sending the dollar to record highs against the British pound and near-record highs against the Euro. But the market doesn’t think dollar strength is sustainable, and worries about a volatile response in government bond markets.

Under these circumstances, gold provides a hedge against whipsaws in monetary policy. That’s why the market considers gold a less risky asset than TIPS or other paper instruments.