Additional reporting by Anton Delgado, Meng Kroypunlok, Roun Ry and SourceMaterial

When the Cambodian rainy season turns dirt roads into rutted mud, the villages tucked into rugged folds of the western Cardamom Mountains can feel far from just about everything.

In the Areng Valley, a river-carved flatland in the range sparsely populated by villages of indigenous Chorng people, that includes any semblance of cellular reception.

This means it’s usually best to meet in-person with Reem Souvsee, the deputy chief of the valley’s Chomnoab commune. Otherwise, Souvsee explained, she might get some reception near the roof of her house, or up the neighbouring mountains where local men go to harvest resin from trees to sell for a bit of income.

Despite that isolation, in recent months this stretch of rural communities amongst densely jungled peaks has been pulled into the centre of global debate about carbon credits – a development scheme organised under a U.N.-backed framework called REDD+.

These credits are intended to limit the emissions that cause climate change by preventing deforestation in places like Areng. They’re purchased by major polluters, including some of the world’s largest oil and gas firms, to offset their fossil fuel emissions by essentially sponsoring the protection of forests, in developing countries such as Cambodia.

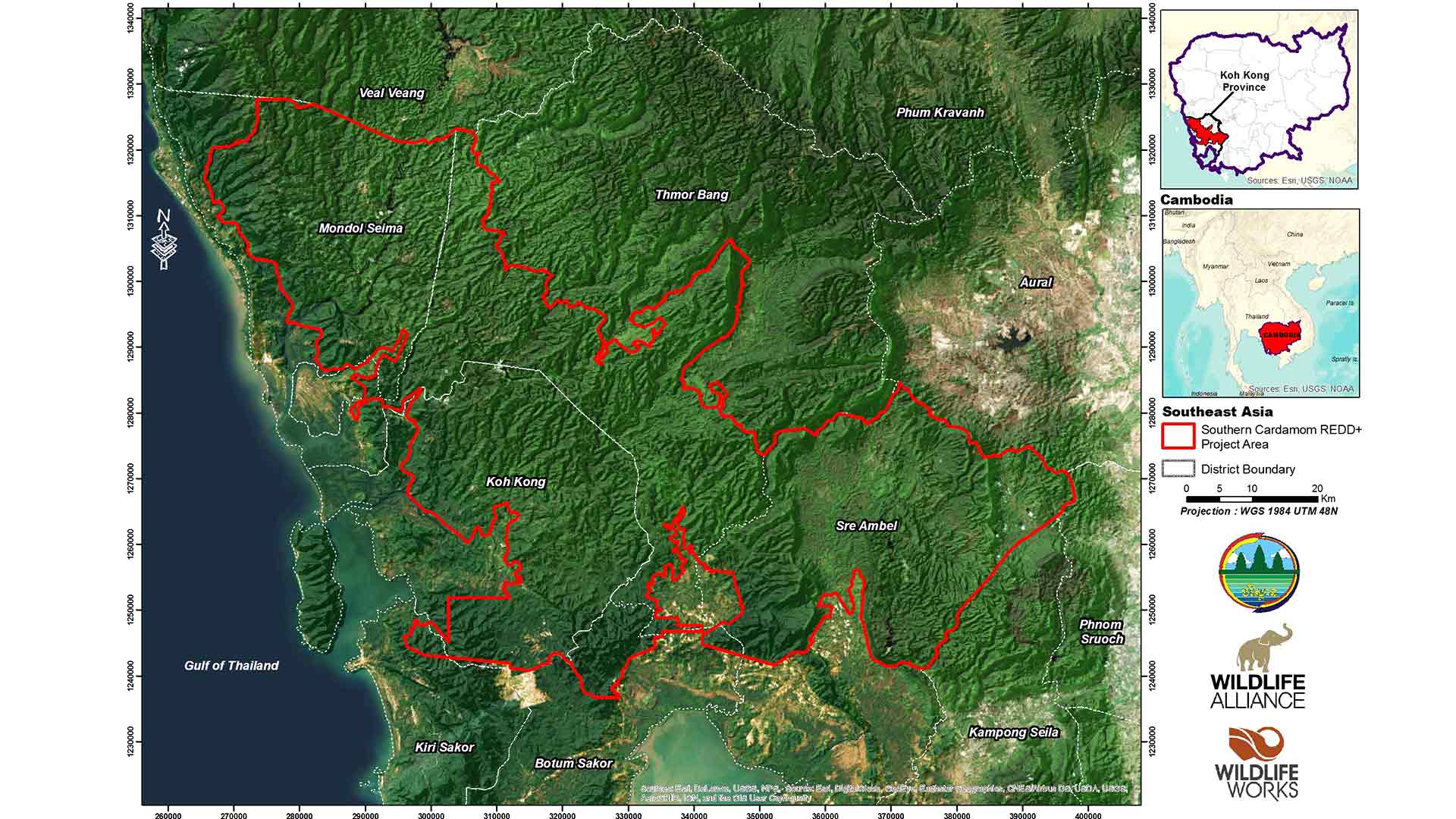

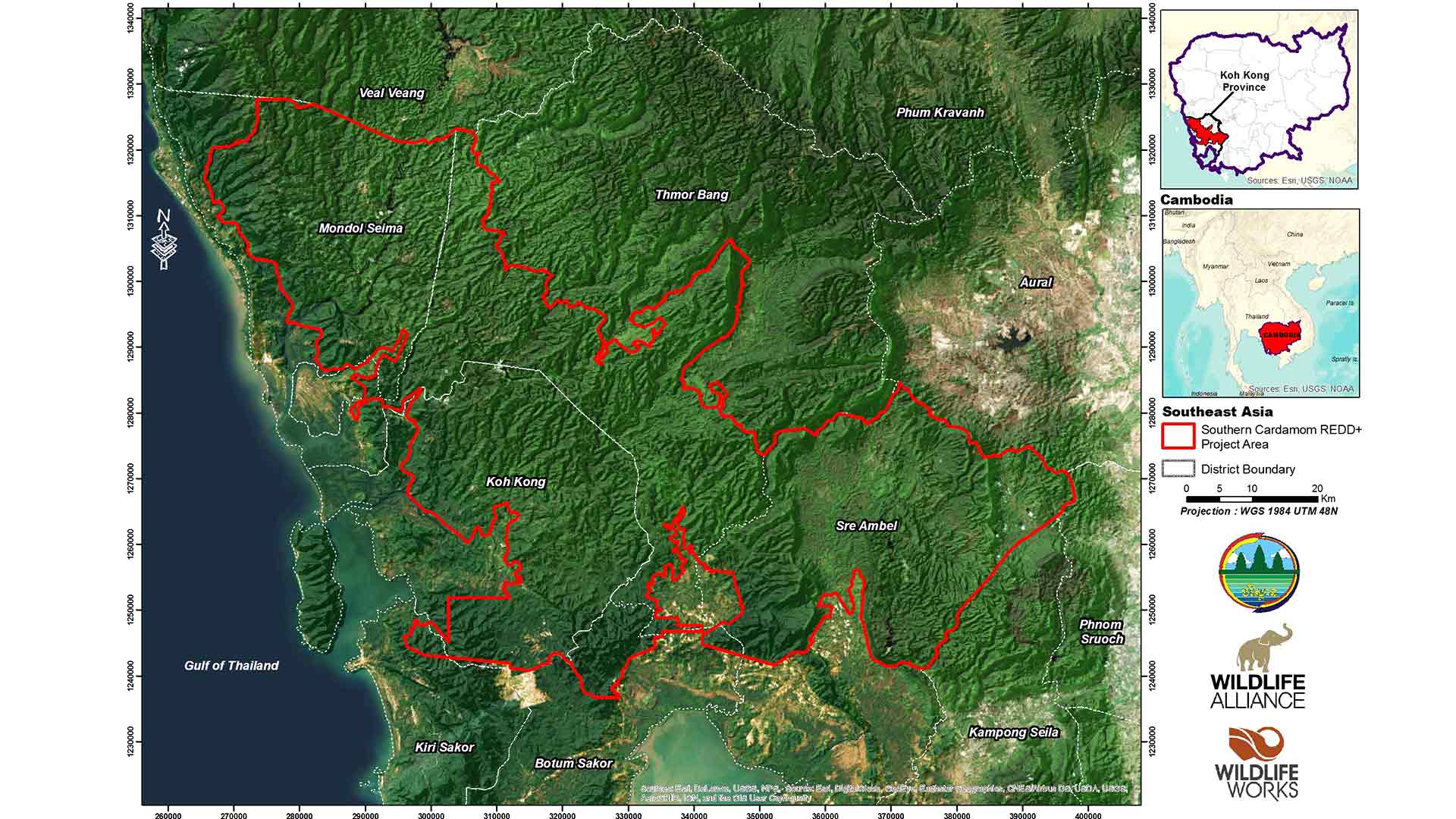

Some of these credits are already coming from the mountains near Souvsee’s home, which lies within the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project. Managed by the nonprofit Wildlife Alliance in partnership with the Cambodian government, the roughly 4,453-square-kilometre project in Koh Kong province includes portions of two national parks and another officially protected area. It is the largest of four such registered carbon credit zones in Cambodia.

The project has also been seen abroad as one of the flagships for the burgeoning climate finance sector. But that image took a major hit in June when the world’s leading carbon credit registry service, a U.S.-based non-profit called Verra, abruptly suspended issuing new credits for the site in response to an as-yet unreleased investigation from global advocacy group Human Rights Watch alleging rights abuses by environmental officials and rangers within the project area.

The finer mechanics of the carbon credit model are mostly unknown to locals in Areng, who were unaware of these developments. But Souvsee – a member of Cambodia’s besieged political opposition Candlelight Party and a former affiliate with the conservation activist group Mother Nature – saw reason to support the programme, which has funded local infrastructure and community development.

“We want REDD+ to be here, but we want them to respect our rights as indigenous people,” she said. “They can help protect our forest, our culture – and they can help protect [our land] from companies too.”

For rural forest communities such as those of Areng, the threat presented by outside companies is very real.

Rights organisations annually rank Cambodia among the most corrupt in the world, pointing to well-documented elite networks that have granted themselves near-total control of the Kingdom’s natural resources under a sprawling political patronage system. This has seen the country’s once-vast forests and other officially protected landscapes traditionally doled out among an overlapping class of tycoons and politicians, usually to be stripped for timber and developed into agricultural plantations.

At the same time, the Cambodian government has pledged to expand carbon credit programmes across its many officially protected areas, as well as a deepening partnership with regional finance hub Singapore to bring its sprouting credits to a global market.

The Ministry of Environment has announced at least eight credit projects in the works in recent years, with two currently awaiting registration with Verra. Officials didn’t answer questions about their plans when contacted by a reporter.

Some conservationists argue the basic financial premise of REDD+ offers an alternative path forward, a means of changing the status quo for forests in Cambodia and other developing countries. They say credit sales provide a funding model that’s actually sustainable on the ground, allowing for more concerted efforts to protect nature. Project developers also assert a system that rewards states for keeping trees standing – as opposed to clear-cut for timber, mining or other development – is a much-needed step in the future of environmental protection.

But critics say these plans still fail to defuse the key drivers of deforestation by powerful economic interests, especially in countries such as Cambodia where land rights and environmental protections wither in the face of political clout and profit-seeking. Worse, some say, the brunt of the protections brought with REDD+ often fall on some of the world’s poorest communities – often smallholder farmers who depend on forests to eke out subsistence livelihoods.

“I think there’s been a growing disappointment with REDD+ projects,” said Professor Ida Theilade, a forestry expert with the University of Copenhagen. She’s studied Cambodia for more than 20 years and has, in the past, done consulting for carbon credit projects in other countries. “It’s very hard to find those success stories, those really big stars in the sky.”

The recent Verra suspension has pulled that critical spotlight squarely on the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project.

Verra stated it was investigating the situation in Southern Cardamom further, but didn’t comment beyond that. Human Rights Watch also did not disclose their report to the Globe.

Though minimal details from the group’s study have been made public, its researchers had reportedly documented rights violations carried out against local people by public officials and conservation rangers in the development of the REDD+ project.

Even just a hint of these preliminary findings was immediately familiar to many in Cambodia.

Though the forests under its watch remain some of the thickest in the country, Wildlife Alliance has long been accused of heavy-handed enforcement of environmental restrictions with often-impoverished local villagers. The not-yet-public Human Rights Watch report likely taps into this history.

Suwanna Gauntlett, Wildlife Alliance CEO and founder, denies abuses, saying her organisation is working to support rural livelihoods while safeguarding protected areas. She places the group’s role in Cambodia in a longer arc of conservation in the Kingdom, tracing back to the group’s earliest days in 2000 – operating in a near-lawless environment to fight land-grabbing, human-caused forest fires and widespread poaching.

“We used to be the good guys doing good stuff, and now we’re the villains,” said Gauntlett, reflecting on the spotlight cast on her group by Human Rights Watch. “I don’t know how comfortable I feel in my new role.”

On the ground

The Southern Cardamom REDD+ project seemed to provide a ready case study for bigger questions facing climate financing in Cambodia. So as part of a broader investigation of greenwashing conducted in partnership with the Earth Journalism Network, reporters from the Southeast Asia Globe and the U.K.-based outlet SourceMaterial, spent about a week total travelling through the Southern Cardamom zone over two separate trips.

With regular check-ins and surveillance from local police, reporters spoke with more than 30 people in communities around the area. These interviews ranged from villagers and local officials to Wildlife Alliance employees.

What they found was – a mixed bag.

“On the whole, we’re happy with REDD+,” said Chhan Kong, 41, a fisherman and rice farmer living in the village of Teuk La’ak. “[But] the rangers can be harsh and aggressive.”

When he and others ventured into the protected area to make camp and fish – a permitted activity – Kong said they ran the risk of having their camping equipment confiscated or destroyed by rangers.

This was a common thread in many interviews, and locals also told reporters they felt compelled to run at the sight of rangers lest they run afoul of restrictions. Those caught breaking the rules could be sent to court, villagers said.

Maybe the most notable recent incident in the REDD+ zone that the Globe heard of involved a then-62-year-old woman who was briefly detained by rangers about two years ago. Presumably on the way to their station, the rangers let her go with no further action after other community members went to advocate for her release.

Still frightened and confused, she told reporters the rangers had picked her up for cutting a small tree near her farm.

As with her case, the single-most common appeal was for greater communication and cooperation, especially for farmers, fisherfolk and others around the boundaries and enforcement of protected areas. A Wildlife Alliance field official who spoke with reporters said there was signage to mark these edges and showed them a detailed map, but acknowledged it wasn’t distributed to local people.

Hoeng Pov, a Chorng community representative in Areng Valley, said even commune officials often lacked key information about the project.

“We really want to know about accountability – how much [do they earn] from selling carbon, how much do they pay for organisations who do this project and for the communities as well?” he mused to reporters. “Some organisations haven’t addressed people’s concerns, they only talk about their project. [And] after they got money from this project they haven’t let us know how the money was divided.”

Though questions remained, almost everyone reporters spoke with agreed on the importance of protecting the forest.

Besides the carbon-sucking benefits that trees and other plant life provide on their own, cutting them down also has massive impacts on the climate – deforestation contributes as much as 20% to global carbon emissions.

According to the nonprofit Global Forest Watch , Cambodia has lost about 31% of its tree cover since 2000, amounting to about 1.57 gigatons of carbon emissions.

At the same time, its forays into carbon crediting have produced mixed results.

Of its four Verra-registered REDD+ projects, two have experienced severe deforestation. One of these is in the province of Oddar Meanchey and the other is called Tumring, located on the edge of the country’s once-vast, now-vanishing Prey Lang forest.

Regarded as the largest lowland evergreen forest remaining in mainland Southeast Asia, even the protected areas of Prey Lang are steadily dissolving under industrial-scale logging operations.

Tumring was developed in partnership with the South Korean government, but primarily overseen by the Cambodian Forestry Administration. The forester Theialde said satellite imagery has shown dramatic loss of tree cover at the project site, and it’s unclear if it’s actually selling credits.

Oddar Meanchey, Cambodia’s first foray into carbon crediting, has suffered a similar fate. With backing from the U.N. Development Program, the project initially found commitments from organisations such as Disney and Virgin Airlines to buy credits. But the corporate backers cancelled after it became apparent that local officials and military units had asserted their own claims to officially protected land.

Meanwhile, Cambodia’s second-largest REDD+ project – managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) at the Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary in the northern province of Mondulkiri – is generally considered a success.

Colin Moore, the Southeast Asia regional REDD+ coordinator for WCS, said revenues from the credits sold from the project have been a game-changer for the group’s work on the site.

“It’s really allowed us to scale our activities on the ground,” said Moore. “We’ve only very recently entered a world where you can do more than just fund a bare-bones conservation programme in these landscapes.”

Moore said WCS works with Everland, a company based in the U.S., to market and sell the credits from REDD+ projects to buyers around the world. Everland also does the same for the Southern Cardamom project.

When credits are sold from Keo Seima, a portion of their sales revenue goes to Everland or other fees, but the rest of the proceeds are split between WCS Cambodia and the Environment Ministry. Moore said the breakdown is 20% for the ministry, 80% for the project itself, deposited into an account managed by WCS.

That latter pool of money goes into funding conservation projects within Keo Seima, including personnel costs and programming related to rural livelihood development, community land titling and more.

Both Moore and Wildlife Alliance declined to say how much in total funding their credit sales have made over the life of the project so far. Local media has quoted government officials stating the Environment Ministry itself has raised $11.6 million in carbon credit sales since 2016, which would be only a portion of the total revenues.

Moore said the successes of the Keo Seima and Southern Cardamom REDD+ projects were the “proof of concept” before the Cambodian government’s current push to develop more credit programmes. A boost in global interest in financing such projects since 2021 – the first year of the Paris Climate Accords commitment period – also helped drive interest, he added.

“The existing projects that were here in Cambodia had been ticking along, eking by on some small sales here and there,” Moore said. “Only after 2021 did they start to make big sales, be able to move their inventory.”

Critiques and hopes

Conservation funding aside, critics of REDD+ have not found it a convincing model to mitigate climate change.

An extensive report from a carbon trading research centre at the University of California-Berkeley asserted last month that loose REDD+ assessments and quality control practices by Verra are leading to “over-crediting” and “exaggerated” claims about the impact of such projects.

As a result, they said, credits sold under the promise of directly offsetting specific amounts of carbon emissions likely represent only “a small fraction of their claimed climate benefit”. The researchers also wrote that REDD+ projects focus their enforcement efforts on rural, often-impoverished forest communities while remaining unable to address large-scale deforestation caused by more powerful economic interests.

“Our overall conclusion is that REDD+ is ill-suited to the generation of carbon credits for use as offsets,” the researchers wrote, adding that the current “market system creates a race to the bottom that is hard to emerge from.”

Those within the sector itself have a different view.

Everland President Joshua Tosteson freely admits the industry is imperfect but is adamant that its basic premise is a good one when done properly. He said he hadn’t read the Berkeley report in depth, but noted that he agreed with it that the Verra system allowed for a “wide variability right now in respect to how projects get set up in relation to the communities.”

“There isn’t really like what you might call a normative standard, a quality standard for how things ought to be done,” he said, adding that applied to things such as gaining free prior and informed consent and revenue sharing with local people.

That makes it hard to properly gauge how well projects actually address the underlying social and economic reasons for forest loss, Tosteson added.

Beyond that, he rejected the larger denunciations of the Berkeley report, ascribing some of its findings to a broader wariness of using market solutions to address deforestation or climate change issues. However, for a country such as Cambodia, he thought the financial incentive that REDD+ brought to conservation could help keep trees standing.

“The thing about REDD that I think people do not appreciate and understand is that money talks – and the fact that there has been financial success associated with forest conservation in these two places [Southern Cardamom and Keo Seima] is beginning to change the mind of the government,” he said. “It’s going to take a while, but this is definitely part of the trajectory that I think can get you to a different ethos at a national level.”

At Wildlife Alliance’s offices in Phnom Penh, Gauntlett and her organisation also stand by their work.

Besides using the revenues from carbon credit sales to fund protection of the REDD+ area, the group also listed a range of material investments in the rural communities of the Southern Cardamom project.

Besides helping start “community-based eco-tourism” centres, Gauntlett also said her group had shored up land tenure for residents in the REDD+ zone by facilitating the government processing of just under 5,000 “hard” land titles – a level of official recognition of ownership often difficult to secure in Cambodia – covering nearly 12,250 parcels of private land there. She expected the Ministry of Land Management to issue an additional 7,249 titles through 2024.

Gauntlett also listed infrastructure developments such as about 28 kilometres of new or rehabbed roads in the project zone, 94 solar-powered water wells, 77 toilets, two schools and a bridge. Wildlife Alliance also funded 16 full university scholarships for students to study and live in Phnom Penh, she said.

Reporters were able to see much of the hard infrastructure for themselves as they traveled through the project area. In the Areng Valley, one older resident said the newly installed toilet was the first she’d ever had.

While the Wildlife Alliance REDD+ programme officially started in 2015, Gauntlett said her organisation had first tried to establish the programme in 2008 – but was rejected by the Cambodian government.

“Finally when REDD started, it was pretty much already all done. It wasn’t a decision that came out of the blue like this,” she said. When asked why the government had initially been against it, Gauntlett was concise.

“Very simple. More money to be made through economic land concessions.”

‘An illusion’

Still, the incentives offered by climate finance will need to compete with more short-term motivations. Not everyone shares Gauntlett’s optimism that carbon credits are up to task.

The forester Theilade is among them. She mostly focuses on the vanishing Prey Lang forest and the community networks that have struggled to maintain it against powerful interests.

She was also involved in the early 2000s with helping the Cambodian government develop its “REDD+ Roadmap”, a planning process with World Bank funding that ostensibly evolved into the Kingdom’s current strategy.

Today, she occasionally reviews conservation proposals with carbon trading components, but she’s not working specifically with crediting schemes.

Theilade is also not involved with Wildlife Alliance or their work in Southern Cardamom but said she’d read about the organisation’s presence there. Though she gave some credit to them, she said Cambodia’s extensive patronage system leaves no quarter for good intentions – especially where forestland is concerned.

Such an outcome for Wildlife Alliance has already happened elsewhere in the country. Last year, its partners in the Forestry Administration conspired against the conservation group with local officials and prominent tycoons to clear-cut and parcel out a smaller forest that Wildlife Alliance had preserved just outside the Phnom Penh metro.

The conservation group had used that area, known as Phnom Tamao, as a sanctuary for rare and endangered animals. Though a rare surge of public discontent put a stop to development of the land, the forest itself was decimated.

Based on global prices for carbon on the offsets market, Theilade thought there was no way for credits to compete with other land uses associated with the patronage system – especially timber logged from protected areas.

Though she gently cautioned that she didn’t want to “sound too negative” about the work being done by some conservation groups to build out such schemes, Theilade just didn’t see it as a realistic option given the political weight against conservation.

“It has to be a government deciding, or a culture deciding, that these forests are worth something to us,” she said, describing the various ecological, social and spiritual benefits that forests provide in Cambodia. “That the government is going to conserve forests for some small carbon payments, I’m afraid, is an illusion.”