Last year a woman in India’s northern state of Bihar was told her daughter’s rapist had died and the case against him closed. She questioned the claim and uncovered the truth, leading to the reopening of the case and ultimately securing justice for her daughter. The BBC’s Soutik Biswas investigates a remarkable tale of perseverance.

On a balmy morning possibly in February last year, two men arrived at a cremation ground on the banks of the Ganges, India’s holiest river.

They were there to perform a Hindu funeral rite. The men were lugging firewood, but were strangely not carrying a corpse.

Once they reached the cremation ground, things took a bizarre turn.

The men built a pyre on the ground. Then, one of them laid himself down on the pyre, covered himself with a white shroud and closed his eyes. The other piled more wood on until only the first man’s head was visible outside the cage of sticks.

Two photographs of these scenes were taken. It is not clear who took the pictures or if a third person was present.

The “dead” man was apparently Niraj Modi, a 39-year-old government school teacher. The other man was his father, Rajaram Modi, a wiry, sixty-something farmer.

Rajaram Modi then travelled to a court, some 100km (62 miles) away, with a lawyer and swore a signed affidavit that his son Niraj Modi had died on 27 February at their village home. He also supplied two pictures from the cremation and receipts of the firewood bought for the ritual as evidence.

This was six days after police had framed charges of rape against Niraj Modi. Modi was accused of raping a 12-year-old girl, who was also his student, in October 2018. The girl had been set upon when she was alone in a sugarcane field and her attacker claimed he had filmed the assault and would release the footage online.

Modi had been arrested soon after a complaint was lodged by the mother of the girl, and was out on bail after spending two months in prison.

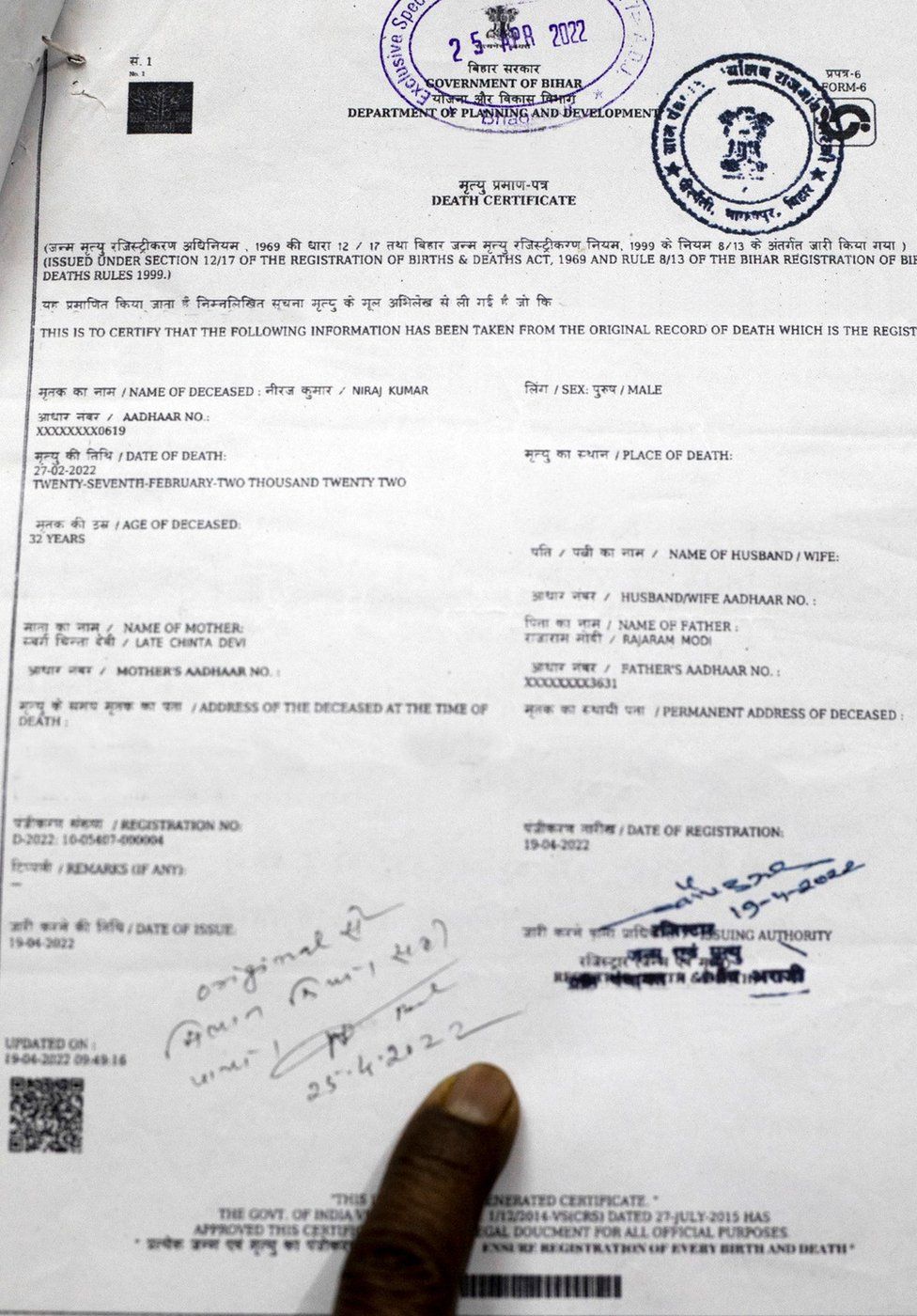

Things moved swiftly after Niraj Modi’s “death” last year. Two months after his father informed the court, local authorities issued his death certificate. In May, the court closed proceedings as the “only accused in the case” was dead.

Only one person suspected that the teacher had faked his death and had gone into hiding to avoid conviction – the girl’s mother, a frail woman who lived in a shack in the same village as the Modis.

“The moment I came to know that Niraj Modi was dead, I knew it was a lie. I knew he was alive,” said the mother when I met her recently.

Seven in 10 deaths in India occur in the country’s nearly 700,000 villages, and in villages far more deaths occur at home than is the case for deaths in cities. A 54-year-old law requires compulsory registration of the facts of births and deaths – but not causes of death.

When a person dies in a village in Bihar, a family member of the deceased has to submit his or her unique biometric identity number, and obtain the signatures of five residents of the village who attest to the death.

These need to be then given to the local panchayat or village council. Its members, including a local registrar, examine the papers and – if everything is in order – issue a death certificate within a week. “Our villages are dense and closely-knit. Everyone knows everyone else. A death is never unnoticed or unheard of,” says Jai Karan Gupta, the lawyer of the victim.

Rajaram Modi had submitted signatures and biometric identity numbers of five villagers and the affidavit saying his son was dead, and obtained his son’s death certificate. The document did not mention the cause of the death. The receipt from the firewood shop said the death was caused by “disease”.

One day last May, the mother came to know from a lawyer that the case against Niraj Modi has been closed because he had died.

“But how come nobody knew of the teacher’s death? Why were no rites held after the death? Why was there no talk about the death?” she asked me.

She said she went from home to home checking from people whether Niraj Modi was dead. Nobody had heard the news. Then she went to the court with a plea to investigate the matter, but the judges asked for evidence to prove the teacher was alive.

In mid-May, the mother petitioned a senior local official, saying that the village council had issued a death certificate based on forged documents, and that it should be investigated.

Things began moving quickly thereafter.

The official ordered a investigation and informed the village council. Its members sought more evidence from Rajaram Modi about his son’s death: photos of the “deceased after his death, of the cremation, of the burning pyre, the last rites and [fresh] testimony of five witnesses”.

Village council members met residents of the village of some 250 homes. Nobody seemed to have heard about the death of Niraj Modi. Head shaving is a Hindu mourning tradition usually reserved for the death of a close relative. Yet none of the Modi family members had shaved their heads.

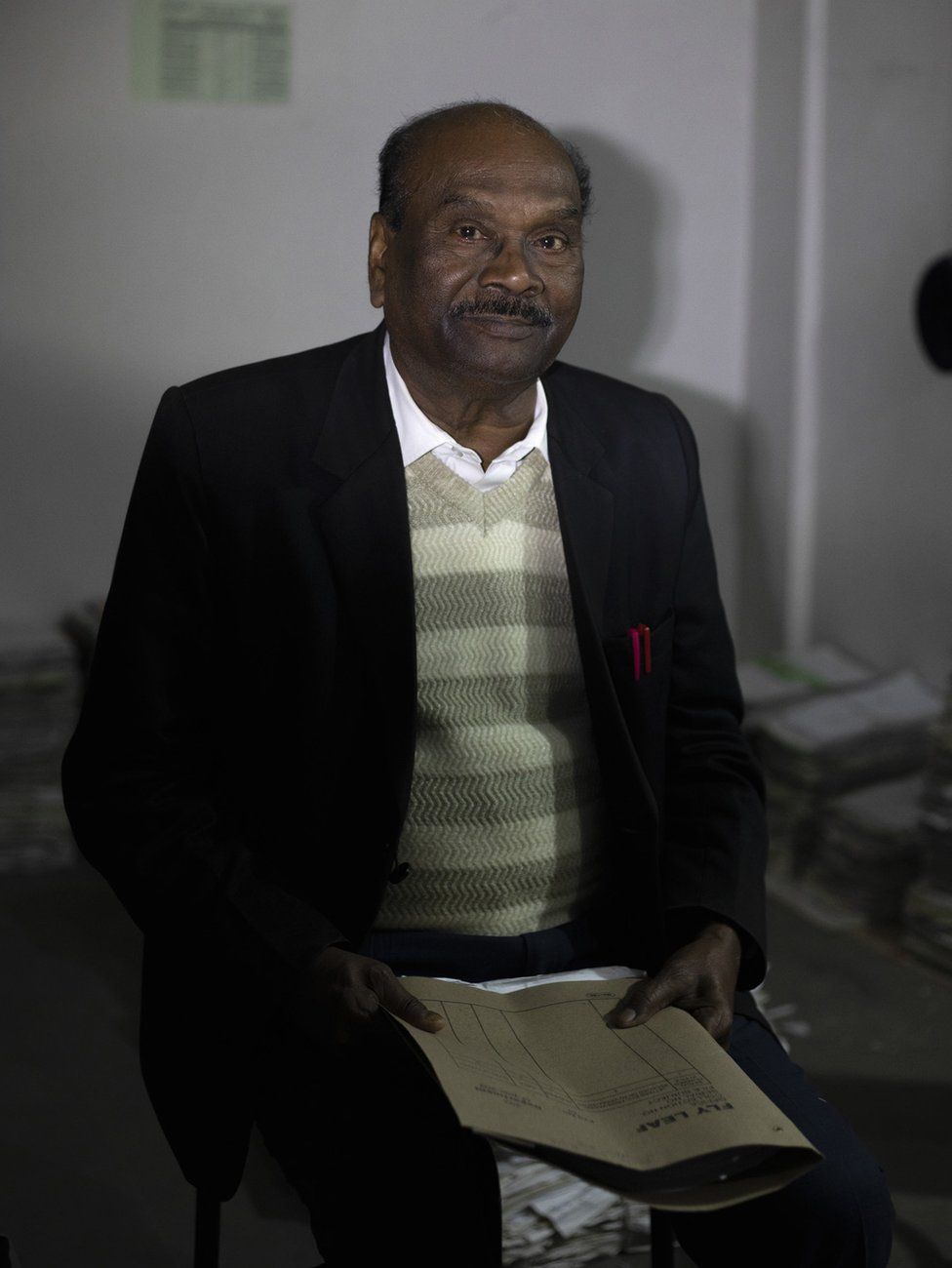

“Even the relatives of Niraj Modi had no information about his death or his whereabouts. They kept saying if there had been a death the final rites would have been held at home,” said Rohit Kumar Paswan, the investigating police officer.

Village council members quizzed Rajaram Modi again. He had failed to provide fresh evidence of his son’s death. “When we asked him more questions, he didn’t give any satisfactory answer,” said Dharmendra Kumar, the secretary of the council.

Investigations concluded that Niraj Modi had faked his death and both father and son had forged documents to get a death certificate.

The police found that the school teacher had taken biometric identity numbers of parents of five of his students and forged their signatures on a paper seeking his own death certificate. He told the parents that he needed their identity numbers for scholarships he was arranging for the students.

On 23 May, officials cancelled Niraj Modi’s death certificate. Police arrested his father and charged him with forgery. “I have never quite investigated a case like this in my career,” said Mr Paswan. “The plot sounded perfect, but it was not.”

In July, the court re-opened the case, saying it had been “deceived and misled” so the accused could “escape punishment”. The mother, relentless in her battle to track down the teacher, went to the court seeking his arrest.

In October, Niraj Modi gave himself up to the court, nine months after he had been declared dead. During the trial he had defended himself, denying the allegations of rape. Now he walked out of the court, downcast and restrained by a rope.

Last month, the court found Niraj Modi guilty of raping the girl and sentenced him to 14 years in prison. It awarded compensation of 300,000 rupees ($3,628; £3,009) to the victim. Rajaram Modi is also in jail facing charges of cheating and dishonesty, which carry a maximum sentence of seven years in jail. Both father and son are now facing charges related to the death certificate.

“For more than three years I travelled to the court to make sure the man who assaulted my daughter would be punished. And then one day his lawyer told me he was dead. How could a man vanish into thin air just like that?” the mother says.

“The lawyer told me it will cost a lot of money to fight a new case to prove that the death was faked. Others told me that the accused would come out of jail and take revenge.

“I didn’t care. I said I will arrange the money. I’m not afraid. I told the judge and the officials: ‘Find out the truth’.”

We drove for hours on potholed roads past open sewers, shanty huts, yellow mustard fields and smoky brick kilns to reach the victim’s higgledy-piggledy village, deep in the interior of Bihar, one of India’s poorest states.

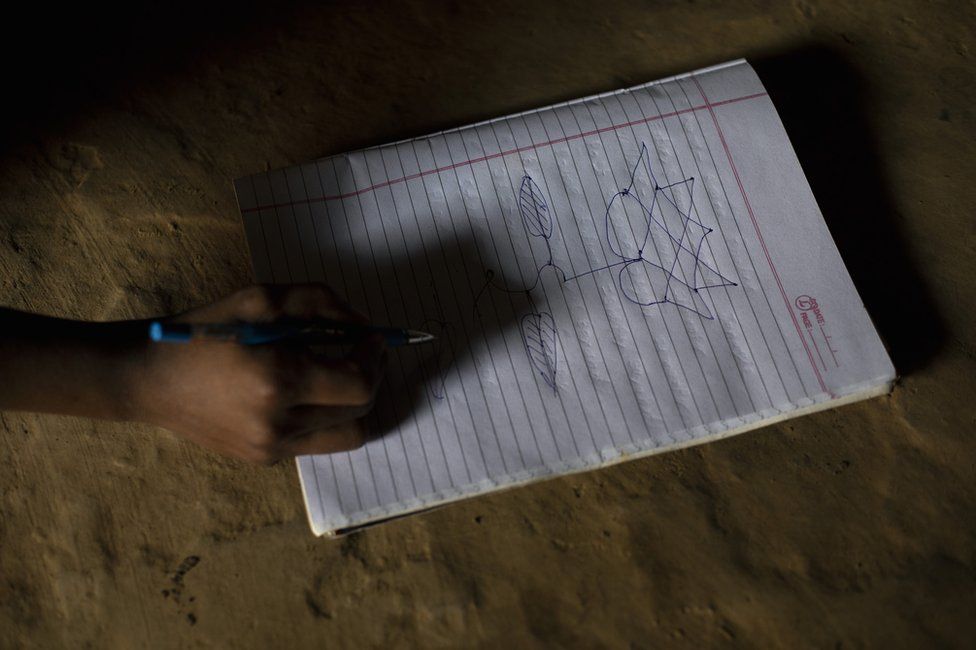

A narrow, paved street snaked through a warren of squat brick homes covered with satellite dishes. The mother lived with her two school-going sons and her daughter in a small windowless brick room with a corrugated tin and tile roof. Her eldest child, a daughter, was married and lived elsewhere.

The gloomy, dark room had bare belongings: a rope and wood cot, a steel vessel to store grains, a clay stove sunk in the ground and a tatty clothes line. The family had no land to live on.

The village had piped water and electricity, but no jobs so the girl’s father had migrated to a southern state, more than 1,700km (1,056 miles) away, where he worked as a loader and sent money home.

In 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that 100% of India’s villages had declared themselves free of open defecation after a massive toilet-building programme by his government. Yet many homes – including the mother’s – still lack a toilet.

That was why her daughter had gone to use a nearby sugarcane field as a toilet. That was when Niraj Modi had walked up to her from behind, shut her mouth and forcibly raped her, according to Judge Law Kush Kumar in his verdict. He had also told her to keep silent as he had recorded a video of the act and threatened her he could make the video viral, the judge said.

Ten days after the assault, the frightened girl told her mother about it. Her mother went to the police: over the next few days, her daughter gave evidence. “Niraj Modi would often beat me up at school,” she told the police.

The girl resumed going to school after Niraj Modi was arrested, but stopped when he came out on bail. She hasn’t been to school in four years now. Her school books have been sold off to a scrap dealer.

A pale and nervous figure, the girl now spends most of her time in the dark room. “Her life as a student is over. I am too scared to let her go out. I hope we can get her married,” her mother said.

Many questions remain unanswered. How did the village council issue the certificate without checking the papers properly? “When I challenged them later, they said they had made a mistake,” the mother said.

Prabhat Jha, a professor at the University of Toronto who conceived one of largest studies of premature mortality in the world, said the case of Niraj Modi was “very unusual and rare”. “In our work, we have not come across a single such case,” he said, referring to the ambitious Million Death Study in India.

“The misuse is very likely rare, and we’d have to be more careful to put more restrictions or barriers for the death registration as they may make matters worse,” Mr Jha said.

Reason: since more women than men, and more poor than rich are undercounted in death and medical registration in India, it makes the transfer of assets and other efforts more difficult, and “likely contributes to poverty traps”.

Back home, life appeared to have unravelled for the mother, by turns feisty and stoical, plagued by anxiety.

“I lobbied the village and officials to get to the truth. I am glad that the man who violated my girl and scarred her life is in jail.

“But my daughter’s life has shut down. What will happen to her?”

Read more by Soutik Biswas

- Their son vanished – then an imposter took over for 41 years

- The Indian ‘germ murder’ that gripped the world

- When a cobra became a murder weapon in India

- Five murders, six men and 16 years of stolen lives

- A kidnapped girl, a skeleton and a house of memories

- Who sent the wedding gift bomb that killed this newlywed?