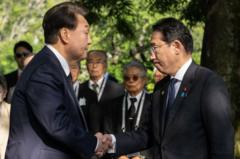

The United States and China have achieved what many deemed impossible – a historic meeting between US President Joe Biden, Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korea’s President Yoon Suk-yeol.

Mr Biden is hosting the first stand-alone meeting among the three countries at the Camp David presidential retreat in the US on Friday. It’s a diplomatic – but still tenuous – coup for the American leader.

South Korea and Japan are neighbours and old US allies, but they have never been friends.

Now, however, an increasingly assertive China has renewed US interest in East Asia. And it has brought together two countries who for decades have struggled to overcome deep historical grievances.

“I find the meeting at Camp David mind-blowing,” Dennis Wilder wrote on X. A professor at Georgetown University, Mr Wilder managed the Japan and South Korea relationship under former President George W Bush.

At that time, they could “barely get South Korean and Japanese leaders to meet with us in the same room,” he said.

In recent months, Mr Kishida and Mr Yoon have taken tentative steps to resolve their hostilities, and strengthen ties with Washington. This once-inconceivable alliance is driven by shared concerns – the biggest of which is China.

The meeting at Camp David – also the first time foreign leaders have visited the presidential retreat since 2015 – is an attempt to “signify and to demonstrate how seriously” Mr Biden takes the relationship between Japan and South Korea, according to a White House spokesman.

“The Camp David summit is truly historic, unimaginable until now, because the Seoul-Tokyo relationship was always fraught with historical disputes miring the two legs of the triangle,” says Duyeon Kim from the Indo-Pacific Security Program at the Center for New American Security in Seoul.

“It’s an extremely rare opportunity for the three countries to propel their vision to the next level. They should seize it and push ahead boldly on even ambitious issues before presidential election cycles test or even strain the durability of their commitments.”

Why has it taken this long?

For one, the wounds are old.

Some may describe the two countries as “frenemies”, but it’s too trite a term to describe the deep hurt among South Koreans, including the thousands of so-called “comfort women” who were abducted and used as sex slaves by the Japanese army during Wold War Two.

South Koreans believe the Japanese never properly apologised for the colonisation of the Korean peninsula from 1910 to 1945. Tokyo, however, argued that it had atoned for its historical sins in several treaties.

Any detente has always been fragile, almost akin to a game of Jenga. Even when the East Asian bloc appeared solid, a single wrong move could bring the whole edifice down.

In 2018, a long-running court case in Seoul over Japan’s use of forced labour during WW2 started a trade dispute which plunged relations between the neighbours to their lowest since the 1960s.

But there has been progress recently, including a milestone meeting in March, offering Washington a new window of opportunity.

But there is a good reason for the two new administrations to put their differences aside, even at the cost of political capital on the domestic front.

This is, after all, the era of pragmatic politics – and they see a bigger threat looming.

China’s assertive posture in Asia has alarmed its neighbours. Beijing claims Taiwan, a democratically governed island, and has not ruled out the use of force to “unify” it with the mainland. Incursions into Taiwanese airspace and major military drills are now the so-called “new normal”.

There is also North Korea. which has carried out more than 100 weapons tests since the start of 2022, including firing missiles towards Japan. The war in Ukraine too has prompted many countries, including South Korea and Japan, to prioritise national security.

All of this appears to have helped Mr Biden win where previous administrations in Washington have failed.

“This marks a major milestone in the history of the trilateral relationship that has moved in fits and starts over the last three decades,” said Andrew Yeo, the SK-Korea foundation Chair at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

He says the three sides will aim to “cement the gains” they have made in the last year or so, “while building momentum… to address a range of security challenges in north-east Asia and the Indo-Pacific region”.

That would mean signing agreements on defence, diplomacy and technology. It’s already known that they will agree to hold regular military exercises, set up a new three-way crisis hotline and, crucially, pledge to meet once a year. Washington’s goal then is to establish long-term ties that will last well beyond the sitting presidents.

“Biden, Yoon and Kishida have a chance to make even bigger history that lasts beyond a milestone meeting at Camp David,” said Duyeon Kim.

“Their respective governments will need to implement their joint vision proactively and beyond their leadership terms because the Seoul-Tokyo relationship will continue to ebb and flow. If an ultra-leftist South Korean president and an ultra-right-wing Japanese leader are elected in their next cycles, then any one of them could derail all the meaningful, hard work Biden, Yoon and Kishida are putting in right now.”

And here lies the challenge.

Will it last?

Kurt Campbell, Deputy Assistant to President Biden and Co-ordinator for Indo-Pacific Affairs, has praised the “political courage” of Mr Kishida and Mr Yoon, calling it “a breathtaking kind of diplomacy”.

But a change of leadership could see a change of heart.

“Tensions that run deep, particularly in South Korea due to past historical animosities related to Japan’s colonisation of Korea, do not disappear overnight, and we’re likely to continue to see diplomatic spats arise, as was the case a couple of weeks ago when the Japanese ministry of defence claimed Dokdo (Takeshima islands) as its own in its national security strategy,” said Andrew Yeo.

“Relatively low approval ratings for Kishida and Yoon back at home may limit the amount of diplomatic capital the two leaders could sink into Korea-Japan relations. I also believe at some point the two sides, and Japan in particular, will need a more thorough reckoning of its colonial past in Korea and elsewhere.”

Japan and South Korea may also not want to go as far as Mr Biden in criticising China. Fearing a backlash, they may hardly mention Beijing in their public remarks following the summit.

And pacts involving economic measures might be harder to secure than agreements on national security.

US-China tensions, especially economic restrictions, have come at a cost to both South Korea and Japan. China is a key trading partner for both. And companies in Seoul and Tokyo – such as Samsung and Nissan – rely heavily on Chinese workers and consumers.

Beijing has already made its displeasure over the summit known. It will see it as yet another attempt by the US to “contain” its influence, no matter how much the White House denies this. It has already dubbed it a “mini-Nato”.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi urged South Korea and Japan to work with Beijing to “revitalise East Asia”.

In July, in a video that has now been widely shared, he made an unusually blunt appeal: “No matter how blond you dye your hair or how sharp you shape your nose, you can never become a European or American, you can never become a Westerner. We must know where our roots lie.”

While Mr Biden has – successfully perhaps – focused on building defence alliances in Asia, it has left little room for engagement with Beijing and Pyongyang.

There were signs this was changing, with a flurry of recent Beijing visits by senior US officials – Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and US special envoy on climate John Kerry. There are also reports that Washington has approached the North Korean leader Kim Jong Un with an offer of high-level talks “without preconditions”.

But time is running out as another US election cycle begins.