Falling birth rates are a major concern for some of Asia’s biggest economies.

Governments in the region are spending hundreds of billions of dollars trying to reverse the trend. Will it work?

Japan began introducing policies to encourage couples to have more children in the 1990s. South Korea started doing the same in the 2000s, while Singapore’s first fertility policy dates back to 1987.

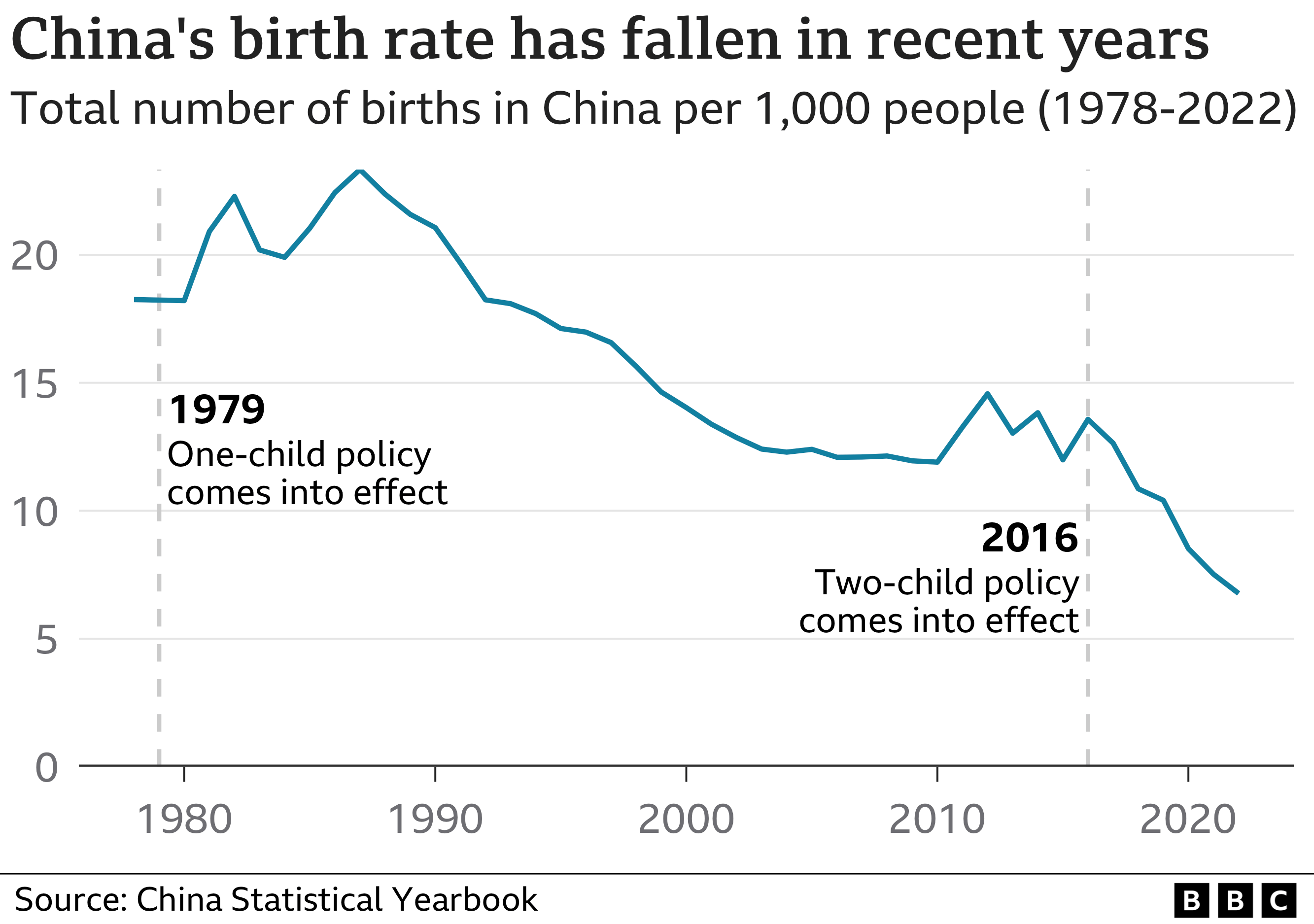

China, which has seen its population fall for the first time on 60 years, recently joined the growing club.

While it is difficult to quantify exactly how much these policies have cost, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol recently said his country had spent more than $200bn (£160bn) over the past 16 years on trying to boost the population.

Yet last year South Korea broke its own record for the world’s lowest fertility rate, with the average number of babies expected per woman falling to 0.78.

In neighbouring Japan, which had record low births of fewer than 800,000 last year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has pledged to double the budget for child-related policies from 10tn yen ($74.7bn; £59.2bn), which is just over 2% of the country’s gross domestic product.

Globally, while there are more countries that are trying to lower birth rates, the number of countries wanting to increase fertility has more than tripled since 1976, according to the most recent report by the United Nations.

So why do these governments want to grow their populations?

Simply put, having a bigger population who can work and produce more goods and services leads to higher economic growth. And while a larger population can mean higher costs for governments, it can also result in bigger tax revenues.

Also, many Asian countries are ageing rapidly. Japan leads the pack with nearly 30% of its population now over the age of 65 and some other nations in the region are not far behind.

Compare that with India, which has just overtaken China as the world’s most populous nation. More than a quarter of its people are between the age of 10 and 20, which gives its economy huge potential for growth.

And when the share of the working age population gets smaller, the cost and burden of looking after the non-working population grow.

“Negative population growth has an impact on the economy, and combined that with an ageing population, they won’t be able to afford to support the elderly,” said Xiujian Peng of Victoria University.

Most of the measures across the region to increase birth rates have been similar: payments for new parents, subsidised or free education, extra nurseries, tax incentives and expanded parental leave.

But do these measures work?

Data for last few decades from Japan, South Korea and Singapore shows that attempts to boost their populations have had very little impact. Japan’s finance ministry has published a study which said the policies were a failure.

It is a view echoed by the United Nations.

“We know from history that the types of policies which we call demographic engineering where they try to incentivise women to have more babies, they just don’t work,” Alanna Armitage of United Nations Population Fund told the BBC.

“We need to understand the underlying determinants of why women are not having children, and that is often the inability of women to be able to combine their work life with their family life,” she added.

But in Scandinavian countries, fertility policies have worked better than they did in Asia, according to Ms Peng.

“The main reason is because they have a good welfare system and the cost of raising children is cheaper. Their gender equality is also much more balanced than in Asian countries.”

Asian countries have ranked lower in comparison in the global gender gap report by the World Economic Forum.

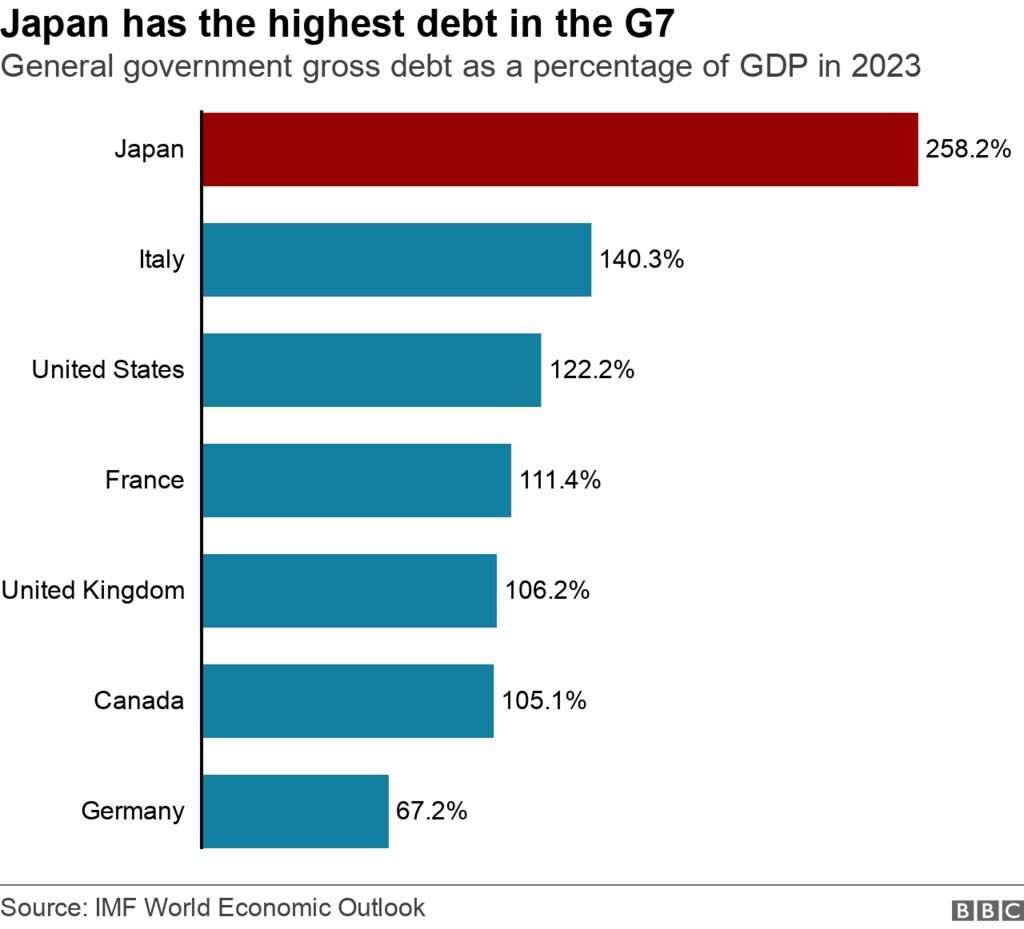

There are also major questions over how these expensive measures should be funded, especially in Japan, which is the world’s most indebted developed economy.

Options under consideration in Japan include selling more government bonds, which means increasing its debt, raising its sales tax or increasing social insurance premiums.

The first option adds financial burden to the future generations, while the other two would hit already struggling workers, which could convince them to have fewer children.

But Antonio Fatás, professor of economics at INSEAD says regardless of whether these policies work, they have to invest in them.

“Fertility rates have not increased but what if there was less support? Maybe they would be even lower,” he said.

Governments are also investing in other areas to prepare their economies for shrinking populations.

“China has been investing in technologies and innovations to make up for the declining labour force in order to mitigate the negative impact of the shrinking population,” said Ms Peng.

Also, while it remains unpopular in countries like Japan and South Korea, lawmakers are discussing changing their immigration rules to try to entice younger workers from overseas.

“Globally, the fertility rate is falling so it’ll be a race to attract young people to come and work in your country,” Ms Peng added.

Whether the money is well spent on fertility policies, these governments appear to have no other choice.