James Villafuerte remembers a few months ago when onions became a luxury in the Philippines.

Rising inflation, the reopened economy and heavy storms combined to spike in demand and short-circuited supply, sending the price of the pungent vegetable soaring to a 14-year high of $12.8 (700 PHP) per kilogram.

“[It got] to the extent that flight attendants were caught smuggling onions from other countries to bring into the Philippines because of the high price,” said the regional lead economist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Such anecdotes have become symbols of a global economy wracked with uncertainty, as the continuing war in Ukraine and increasingly urgent climate crisis fuel concerns over inflation and rising living costs. But a new report from ADB released this month and regional analysts are giving reasons for Southeast Asian optimism in the face of wider global challenges such as flagging growth numbers and rising inflation.

Released Wednesday, the Asian Development Outlook reported a “marginal” downgrade for Southeast Asia’s growth prospects – from 4.7% to 4.6% for 2023 and from 5.0% to 4.9% in 2024 – reflecting weaker global demand for manufactured exports. The latest edition of ADB’s flagship publication focuses on analyses and insights for individual and regional economies across Asia.

Despite the foreboding outlook, experts still believe the region’s interconnectivity, resilient internal markets and the return of international travel will bolster Southeast Asia’s economies against the wider global challenges. Villafuerte noted that while growth projections have slowed, they still exceed those in other subregions and the global average.

“This is a region of 600 plus million people,” said Villafuerte. “Domestic demand remains intact and ‘revenge travel’ has really seen a huge leap in tourism, arrival and tourism related activities.”

Villafuerte acknowledged that global headwinds from elevated prices had contributed to global inflation. On Tuesday, the Philippines central bank announced that policymakers were prepared to tighten monetary policy in view of continually rising inflation.

His remarks came shortly after Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the UN’s major financial agency, voiced similar concerns at last week’s G20 summit. The IMF’s own growth downgrades were predicted at 3.4% in 2022 to 2.8% in 2023, before settling at 3% in 2024.

Georgieva cautioned that economic activity is slowing, “especially in the manufacturing sector”, and called for a stronger “global financial safety net” to help support less-developed countries. But for now anyway, she said the broader economic system is withstanding the pressure.

“The global economy has shown some resilience,” Georgieva stated. “Despite successive shocks in recent years and the rapid rise in interest rates, global growth – although anaemic by historical standards – remains firmly in positive territory, supported by strong labour markets and robust demand for services.”

A history of interconnected trade

While international trade networks remain important, countries are also looking inwards to their own domestic economies.

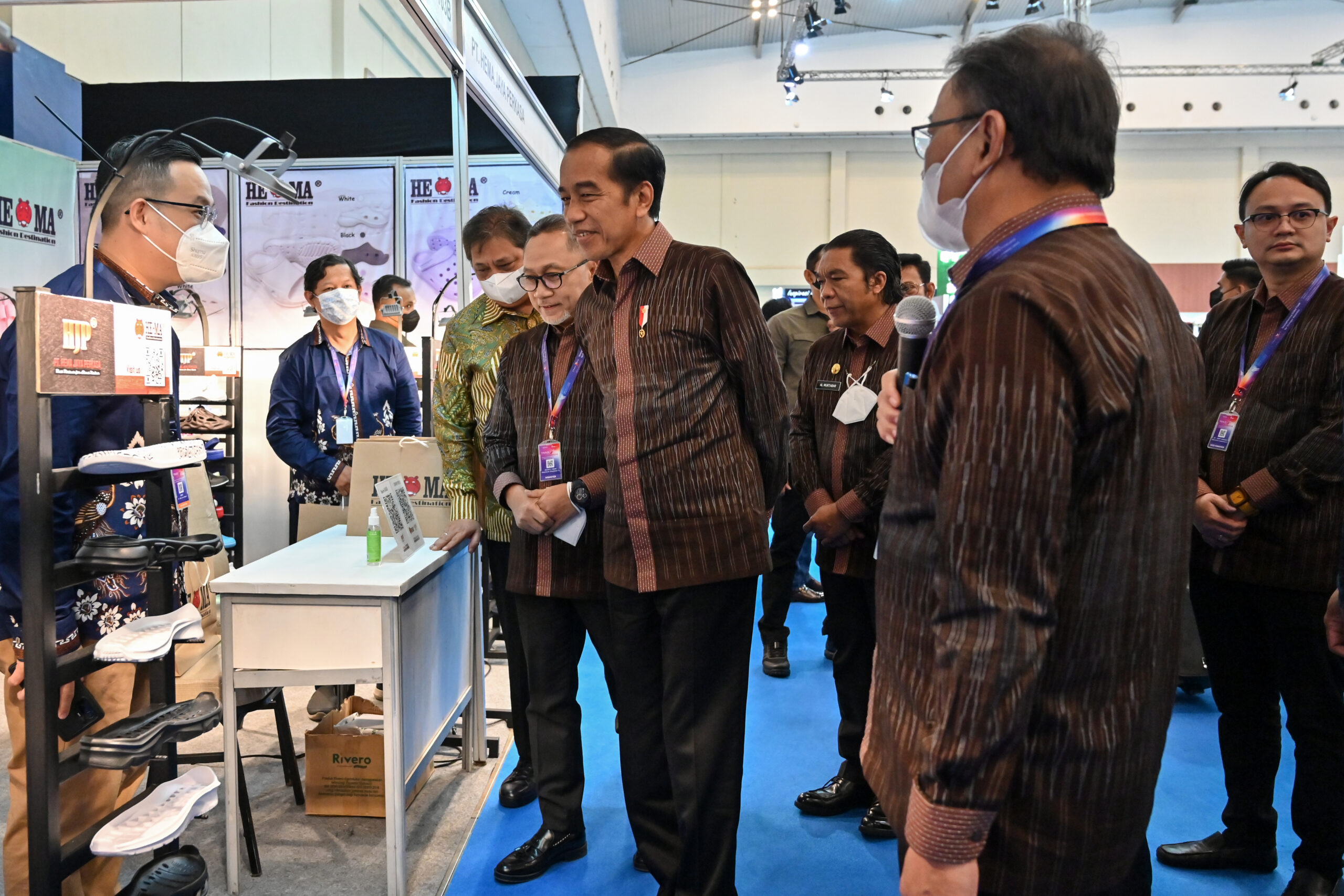

According to the ADB report, while global demand for manufactured goods slowed, domestic demand amongst Southeast Asian countries remained intact. Indonesia’s GDP expanded by 5.03% in the first quarter of this year, and economic growth remained steady, despite a slowing in exports.

Strong national economies can help build on a history of intra-regional connectivity, according to Amanda Murphy, head of commercial banking at HSBC.

“Southeast Asia has long been a bastion of free trade and sits at the crossroads of two of the world’s largest free trade agreements: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP),” she told the Globe.

These agreements, formed in 2018 and 2020 respectively, have strengthened bilateral relations within the Asia Pacific area, creating a network of trade avenues with the advantage of geographical proximity. There are signs this is already paying some dividends.

According to a recent HSBC survey, Murphy explained, over the next two years, Asia-Pacific corporations will place 24.4% of their supply chains in Southeast Asia, up from 21.4% in 2020.

“In particular, RCEP, with its tariff reductions and business-friendly rules of origin, is increasing the appeal of Southeast Asia as a manufacturing base, something more corporates are recognising,” she said.

China

Within the Asia-Pacific region, Southeast Asian countries are planning their next steps with one eye on Beijing. Concerns over China’s slowing economy have caused ripples throughout international markets.

“Weaker growth in the People’s Republic of China has actually weakened the demand for manufactured goods in the region,” said Villafuerte. However some Southeast Asian countries are benefiting from a “China+1” strategy, where global manufacturers look to move production out of China to diversify supply chains and mitigate their risk.

“As businesses seek geographic diversification and adopt the ‘China+1’ strategy, Southeast Asia will continue to gain market share,” said Murphy. “Southeast Asia currently accounts for about 8% of global exports – there is every reason the share can increase.”

China’s exports in June fell to their lowest levels in three years, with a worse-than-expected 12.4% slump from the year before. On the other side of the world, the U.S. also saw a 2.7% export drop at the beginning of the year.

But for Southeast Asia, as trade between superpowers slows, there may be an opportunity to enter new markets and build new relations. As the U.S. and the E.U. have faded as top destinations for Chinese export markets, the East Asian giant has diverged towards other destinations, including Southeast Asia. Chinese exports to ASEAN – the country’s largest trading partner by region – spiked by 20% in October.

For ASEAN’s own export markets, building on critical sectors such as garment manufacturing will help strengthen the bloc’s overall economic outlook despite the global slow-down.

“Excepting [Myanmar], governments in the region are strongly committed to growth, which is fundamental. And this is export-led growth which is even better,” said Gregg Huff, professor of economic development and economic history in Southeast Asia at Oxford University. “Productivity increase is what enables real wages to increase. And if these increase it contributes to political stability.”

Domestic markets

Private consumption was the main driver for economic growth, due to improved labour conditions and income across the region. Some demographics saw an increase in disposable income, according to Singapore’s DBS Bank.

But Elizabeth Huijin Pang, a DBS equity research analyst, was quick to stress at a press briefing that some sectors felt the hit of rising inflation and prices more than others.

“There are still vulnerable groups who have seen the opposite [to our median customers],” she said. “Boomers saw expenses grow faster than income.”

Gig workers were another demographic spotlighted by the bank. DBS data revealed these informal workers to be Singapore’s most financially vulnerable group, with an expense-to-income ratio of 112%, almost double that of a DBS median customer.

“[Gig workers should not be] lagging behind the rest of the population in terms of their longer-term needs,” said Koh Poh Koon, Singapore’s senior minister of state for manpower, at a press conference last week. The remarks come shortly after the government’s agreement to accept recommendations from a workgroup for better representation for gig workers’ needs.

New sectors and opportunities

As well as focusing on vulnerable communities, shifts into new sectors are also a key part of Southeast Asia’s economic recovery. The region is one of the most vulnerable to climate change, and despite a recent decrease in green investments, a shift towards more sustainable business structures will likely be a key part of the region’s growth in its next economic era.

ADB has recently pledged $1 billion (54.4 billion PHP) towards the implementation of electric buses in Davao City, the Philippines’ largest road-based public transportation project.

“I think transforming our growth model into a more environmentally sensitive and green model of growth is important,” said Villafuerte. “When we analyse actually some of these green industries, we realise they also generate a substantial amount of jobs. … These will again be investment opportunities and also opportunities for employment.”

For Murphy, the rise of the regional digital economy is another key focus area for growth.

“Given that more than 75% of its population is online it’s not surprising that businesses are transforming their business models to cater to changing customer behaviour,” she said.

The rise of real-time payments and recent initiatives to facilitate cross-border transactions, such as QR code payment agreements between Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines, are helping to boost the region’s economic connectivity.

“When intra-Southeast Asia real-time payments become a reality, we can expect a jump in the velocity of transactions, whether they are business-to-business or business-to-consumer, which in turn will lead to greater economic activity in the region,” said Murphy.

Transitioning through growing pains

As global crises continue, it is up to Southeast Asia’s private and public sectors to proactively plan their own paths forward.

“Three long-term trends that businesses cannot overlook if they want to capture the opportunities in Southeast Asia are what I would call the 3Ts: trade, transition to net zero, and digital transformation,” said Murphy.

Looking ahead to the future, Southeast Asian nations will have to take a proactive approach to adapt to these growing sectors. Moves are already being made at government level. Both Singapore and the Philippines both recently announced their first sovereign ESG (environmental, social and governance) bond and in April, Singaporean finance minister and Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong revealed the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s finance plan for Net-Zero.

For Vilafuerte, looking forward involves looking back. Governments and market response to the Philippines’ onion inflation earlier this year was almost immediate and prices and supply regulated.

“These are temporary shocks and there are natural stabilisers,” he said. “Higher prices and inflation are a sign of a strong recovery. So I think this is just an adjustment period.”