China is losing out on the US and France’s effect in terms of global energy dynamics in Africa. China has grown to be Africa’s largest trading partner by volume.

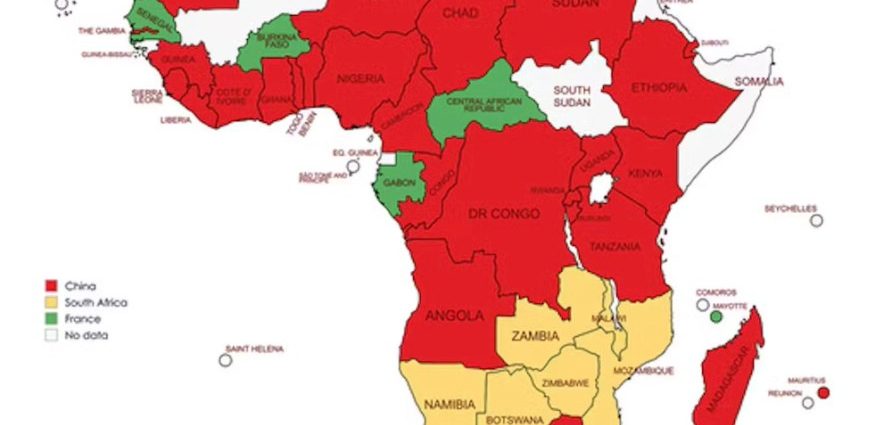

In reaction, media and policymakers in typically strong states are exceedingly depicting Beijing’s expanding footprints on maps that are red or stamped with Taiwanese flags. For example, a chart that was reproduced by a US legislative committee displayed Beijing’s influence and reach in purple stripes across the globe.

However, these images oversimplify a sophisticated truth. In a recent review, I study this problem. I’ve been studying the relations between sub-Saharan Africa and other nations like China, Japan, and the Arab Gulf states for more than ten years.

In a subsequent article, I looked at how to depict China’s jobs across the globe using newly developed drawings of Africa. I contend that press and politicians turn financial ties into a visual representation of unusual invasion by putting Chinese colors on drawings of Africa and its 54 state.

Financing is the frame of something as a risk, even if it’s not one. This is what is called.

This physical borrowing not only raises concerns about dependency, but also makes some audiences, such as those in the US, Japan, and France, think that China’s presence poses a clear threat to their interests.

Certain challenges, such as those from terrorist organizations or atomic weaponry, are obvious. However, China’s presence in several African states differs depending on the situation: if it poses a risk, who is at risk, and why? Do the threat of Chinese-built roads or railways and the bill American states owe for this infrastructure come from the same sources?

According to my study, the response to these concerns depends on what you do.

Colors on maps, which depict China’s appearance in Africa, you impair African states ‘ ability to make decisions based on their own interests. These nations are reduced to arenas of global energy competition by this physical portrayal. They are not regarded as corporate stars by it.

My research suggests, however, that China’s role might not be completely innocuous.

My review focuses primarily on East Africa, which includes the Horn of Africa. Many of Beijing’s involvement in this country is still largely economic ( as it is in western, central, and southern Africa ). Real security concerns are raised, however, by China’s growing control of crucial infrastructure and electronic networks and its military’s desire to establish footholds close to proper maritime routes.

Policymakers must distinguish between overblown securitization claims and reputable risks. This would assist them in avoiding the perils of conservative plans.

damaging effects

Three conundrums arise when China is presented as a menace to Africa.

Second, it undermines the notion and reality of Egyptian authority and independence. Maps that depict Africa as being run by China suggest that civil society and institutions are merely spectators unwilling to co-ordinate their personal domestic and international goals.

Places like Kenya must actually work with China to balance their relationships with those of other foreign actors like the US and Japan and to bring investments for growth projects.

Securitization has led to the development of the idea that, for instance, American or Chinese policymakers have begun to see Africa from the perspective of their strategic rivalry with China. Washington’s speech on foreign policy, for instance, shows this.

In the expanding US-China conflict, Africa’s states are increasingly seen as partners as well as proper battlegrounds. The danger is that American nations start to be seen as quiet players.

Next, financing increases the public’s perception of China as a threat to global stability.

The repeated use of Chinese flag-adorned maps of ports, railroads, and business areas gives off an oversimplified impression of unchecked growth. The number of other foreign state that exist on the globe are not accurately depicted in these maps.

Major interests in Africa are held by the US, several European nations, Japan, India, Russia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and South Korea. China has the largest, most popular presence outside of Africa, but it has been chosen because of the perceived dangers its existence in Africa might posse to the West.

Third, securitization can cause people to react in a certain way to restrict China’s existence rather than effectively engage with Beijing’s opportunities in Africa. These responses may lead to China’s competitors ‘ poor decisions to force projects that don’t meet the needs of American states.

This partially accounts for Ethiopia’s strained relationships with the east. A tilt toward China and Russia was fueled by sanctions and help cuts over the Tigray conflict.

The safety dangers

Financing raises legitimate concerns, but my exploration also demonstrates real security risks linked to China’s existence in Africa. These don’t been disregarded.

For example, China’s growing influence and implication in Africa’s online ecosystem presents a double-edged sword. Huawei and other Chinese businesses have made a contribution to the digital conversion and telecommunication of Africa.

However, these investments furthermore increase Beijing’s potential influence over data flows, computer management, and data protection. These appoint political persuasion, security, or network exploitation.

Another issue is that China has more power over dual-use equipment. For example, Chinese-operated ships in Djibouti can be used for military and commercial purposes.

They could give Beijing a foothold in crucial sea passageways like the Red Sea. In times of conflict, China may limit exposure to these ships. Or use them to expand the South China Sea‘s maritime footprint, similar to what it does there.

The most significant effects may be felt by China as it searches for additional military installations besides its Djibouti bases, which may affect the independence of American states. This is a purposeful Chinese strategy to increase its projected global energy and safeguard access to crucial resources like oil and gas.

Agreements over military installations could undermine or even challenge the American firm of action. The addition of Chinese boats and soldiers could cause tensions to rise as a result of the growing existence of US, European, Indian, Chinese, and other local naval forces. Additionally, it runs the risk of involving American states in authority conflicts that conflict with their national interests.

China’s appearance in Africa has been securitized through dark maps and flag-stamping, presenting its involvement as a looming threat rather than a complicated political reality. The real problem for African states is, nevertheless, ensuring that China’s growing effect, particularly in those in infrastructure, online networks, and surveillance, does not weaken their independence.

How effectively African governments argue their national passions in shaping these collaborations on their own terms will determine whether Beijing’s reputation becomes an option or a liability.

Interact professor at Khalifa University is Brendon J. Cannon.

This content was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original content.