Over the years, agriculture has been a bright spot in an often dark US trade picture. The US traditionally exports more agricultural products than it imports, partially offsetting big trade deficits in manufactured goods. That’s been a point of pride among American farmers and ranchers.

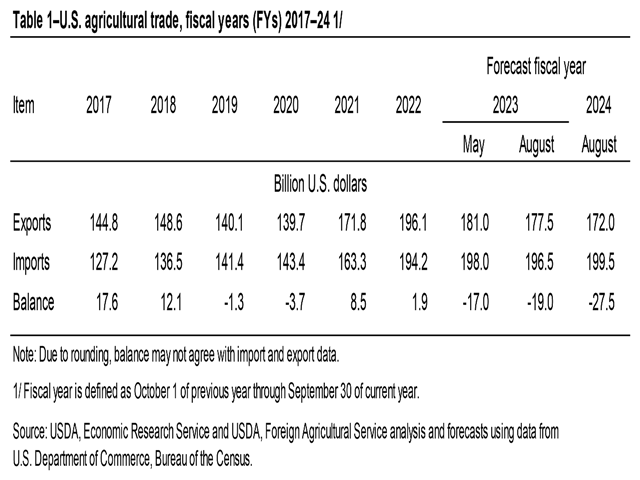

Lately, though, ag imports have outpaced exports. In fiscal 2019 and 2020, the US ran ag-trade deficits of US$1.3 billion and $3.7 billion. Surpluses returned in 2021 ($8.5 billion) and 2022 ($1.9 billion). But now the US Department of Agriculture is predicting a $19 billion deficit for 2023 and $27.5 billion for 2024.

For many, the deficits raise troubling questions. Do they signal a sapping of the vigor of American agriculture? Do they threaten the nation’s food security or farmers’ survival? Are the barbarians at the gate?

For the most part, the answers are no, no and no. That said, it is possible to detect early warning signs:

- On one side of the ledger, increases in imports of particular products that could pose competitive threats, among them beef and some fruits and vegetables.

- On the other side, indications are that ag exports have stopped growing.

During the next couple of years, the US Department of Agriculture is forecasting a big drop in exports, from last year’s $196.1 billion to $177.5 billion this year and a further fall to $172 billion in fiscal 2024.

Could this be the beginning of a trend? While it’s too early to tell, farmers have noticed that Washington isn’t actively pursuing trade deals that would open new markets for US ag. Despite the warning signs, there are still plenty of reasons not to lose sleep over ag trade deficits.

The most obvious and oft-cited one is that a good chunk of American ag imports are crops we don’t grow, like bananas and coffee beans, or out-of-season fruits and vegetables or luxuries like single-malt Scotch whisky.

Consumers covet these products – but in a pinch, or a war, they could live without them, although some of us would suffer from caffeine-deprivation headaches. These imports don’t undermine the country’s ability to feed itself.

Then, too, declining exports don’t mean American crops rot in the fields for lack of demand. Where farmers and ranchers feel the impact is typically in lower domestic crop prices. While that effect is negative, exports are rarely the only thing affecting price. Their decline is in some cases counterbalanced by weather or changes in domestic demand.

Indeed, exports of some products are only retreating because domestic demand for them is so strong. Think soybean oil, which has become a big renewable-fuel feedstock.

A more speculative but still plausible reason not to worry: The export decline may not be permanent. It’s possible exports are just catching their breath after five years of respectable growth, from $144.8 billion in 2017 to $196.1 billion in 2022. A strong dollar has been a big deterrent to ag exports. History suggests the dollar won’t stay strong forever.

Still another reason: The forecast fiscal 2024 export decline is driven by a $3 billion drop in sales to China. US ag has become overdependent on the Chinese market; a correction was probably inevitable and perhaps even healthy.

It would be even healthier were Uncle Sam doing more to open new overseas markets to compensate for China.

While the leaders of the Senate Agriculture Committee, chair Debbie Stabenow of Michigan and ranking member John Boozman of Arkansas, have pushed the administration to use Commodity Credit Corporation funds from a USDA unit that tries to stabilize farm income, what’s really needed if ag exports are to grow are new trade agreements.

The Biden administration isn’t interested. The administration’s major Asian initiative, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, is pointedly dubbed an “economic” arrangement.

It is explicitly not a trade deal. In fairness, it’s hard to believe Congress would approve any trade deal that included the kind of concessions on imports that would be the necessary tradeoff for lowered tariff and non-tariff barriers to US ag exports.

Still, ag trade deficits shouldn’t keep anyone up nights. For some farmers, it may be rational to worry about exports or imports, which could affect them directly.

But ag trade deficits? They may injure farmers’ pride but they won’t put US agriculture out of business or enable an enemy to starve Americans to death. Better to worry about something else.

Former longtime Wall Street Journal Asia correspondent and editor Urban Lehner is editor emeritus of DTN/The Progressive Farmer.

This article, originally published on September 20 by the latter news organization and now republished by Asia Times with permission, is © Copyright 2023 DTN/The Progressive Farmer. All rights reserved. Follow Urban Lehner on Twitter: @urbanize